The Best Animated Fantasy TV Series You May Have Missed

There’s no doubt that this is a great time for fantasy television. From Game of Thrones and its many spinoffs to The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power and The Wheel of Time, there is a veritable treasure trove of fantasy TV for fans of the genre to escape into – and that’s […]

The post The Best Animated Fantasy TV Series You May Have Missed appeared first on Den of Geek.

It might be hard to imagine but there was a time before the internet, before the prequels, even before Revenge of the Jedi was renamed Return of the Jedi. It was a time when Star Wars was something of a new phenomenon. And back then, one of the franchise’s biggest fans was an 11-year-old boy named Rusty Miller who decided he was going to author the first Star Wars quiz book and made it happen.

In a 2020 interview with Skywalking Through Neverland, Matt (née Rusty) explained, “The inspiration came when I saw a trivia book about the works of J.R.R. Tolkien, of which I was also a big fan. And since a trivia book hadn’t been done for Star Wars, I spent the Summer of 1981 coming up with over 600 questions. After finishing the book, my parents sent a manuscript to Del Rey who in turn sent it to Lucasfilm.”

cnx({

playerId: “106e33c0-3911-473c-b599-b1426db57530”,

}).render(“0270c398a82f44f49c23c16122516796”);

});

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the book almost didn’t happen in the more innocent wilds of 1982 (at least in terms of pop culture band-building). Lucasfilm saw little reason to publish the work of tweenage fan—that is until none other than George Lucas himself heard about the project and saved it from cancellation. Shortly thereafter The Jedi Master’s Quizbook debuted on the New York Times bestseller list, and according to its author sold over a million copies.

In 2025 the only copy of the Jedi Master’s Quizbook that you’re likely to find will be in the thrift store, your fave second hand online book store, or the local Friends of the Library store, which is exactly how I got my own copy. The dog-eared paperback is very well loved and once belonged to someone whose name is scrawled in pencil multiple times throughout the pages.

As I scoured through it for the first time in many years, I was blown away not just by Rusty’s extensive Star Wars knowledge but also by what the book said about how fandom, franchises, the concept of canon, and Star Wars itself has changed over the years.

Questions like “Who did Bend fend off at the Cantina?” and its answer “Snaggletooth,” the name of the character that was packaged with the Kenner toy of the character, are a great example of how some things never change. Toys have always played a massive part in determining and revealing canon. That’s something that readers, fans, and filmmakers all still deal with today. But while the struggles of creating art under capitalism are the same, the answer to Rusty’s question is different. Now Snaggletooth is nothing but the nickname of the Snivvian male named Zutton.

This was decades before the internet, so Rusty diligently explored what existed at the time: Star Wars, The Empire Strikes Back, and any info he could find about the upcoming third film, as well as the burgeoning Star Wars publishing initiatives. In another delightful time capsule, as many Star Wars lovers know, Return of the Jedi was then going to be called Revenge of the Jedi. That’s what Rusty put for his answer because the title hadn’t yet been changed due to the decision by Lucas that Jedi cannot feel or seek revenge. Hence that word was saved for decades until we got Revenge of the Sith.

That notion of the ever-shifting nature of canon and even titling is present throughout the book. But it also reminds us that despite all of that, some things never change, or at least they change enough to return back to where they started.

When Miller was collating the Jedi Master’s Quiz Book, Marvel Comics was behind the popular Star Wars comics, something Miller included and that which is a factoid that proves true in 2025. However, as someone who has lived through almost four decades of Star Wars fandom, I can tell you that hasn’t always been the case. Many of the most famous and well-known Star Wars comics for instance were published by Dark Horse. But as the tides go in and out, so do publishing trends. After the sale of Lucasfilm to Disney, Marvel—itself a new Disney subsidiary at the time—took the Star Wars comic book license back from Dark Horse, only for it to currently be shared by both publishers in the present.

It’s an unwritten rule, but in 2025 to make a Star Wars project is to make a story by committee, with decades of canon and continuity to contend with. Conversely, in The Jedi Master’s Quiz Book Miller seemed almost to be the sole holder of the canon of Star Wars, something most fans could never dream of. His dedication and commitment to a galaxy far, far away meant that for many kids growing up, they too got to open up this tome and become keepers of all the facts and canon within it. In an era before Wikipedia and the internet in general, Rusty Miller became one of the earliest in a grand tradition of fans to take canon, sort it, and define it with his own hands.

One of the most fun things about Miller’s work is that you can discover new facts or history that begin to slide into your own personal Star Wars canon. For example in Rusty’s quiz book the answer to “What is Artoo’s robot classification?” is “Thermocapsulary dehousing assister,” as that’s what he was named in the novelization of the movie. That long winded classification would soon be completely replaced with Astromech—at least until the “full” title was referenced in the 2015 Star Wars comics. There are also intriguing things to learn about what was considered canon and what would later be relegated to the non-canon world of Legends.

Although you will rarely, if ever, see Jedi Master’s Quiz Book cited as a key addition to canon now, at the time the world of Star Wars was expanding rapidly and the lore was beginning to grow. Thanks to the early interaction between the films and the novelizations, including the would-be-sequel story Splinter of the Mind’s Eye by Alan Dean Foster, and the Marvel Comics, the Expanded Universe of Star Wars had truly begun. Which would hilariously instantly cause canonical confusions, including that in the novelization of the film, X-Wing pilot Porkins was given the callsign Blue 4 when in the film he was Red 6. He wasn’t the only one either as Wedge Antilles was named Blue 2!

In a world where we couldn’t be further from the conditions in which the Jedi Masters Quiz Book came to exist, the one thing that stays the same is that fans have always been the keepers of these franchises and their facts. It’s that passion and energy that still fuels fan wiki pages and fills convention centers all year round. Thank you for being our fandom forbearer, Rusty Miller!

The post This Old Star Wars Quiz Book Shows Just How Much the Franchise Has Changed appeared first on Den of Geek.

This Old Star Wars Quiz Book Shows Just How Much the Franchise Has Changed

It might be hard to imagine but there was a time before the internet, before the prequels, even before Revenge of the Jedi was renamed Return of the Jedi. It was a time when Star Wars was something of a new phenomenon. And back then, one of the franchise’s biggest fans was an 11-year-old boy […]

The post This Old Star Wars Quiz Book Shows Just How Much the Franchise Has Changed appeared first on Den of Geek.

It might be hard to imagine but there was a time before the internet, before the prequels, even before Revenge of the Jedi was renamed Return of the Jedi. It was a time when Star Wars was something of a new phenomenon. And back then, one of the franchise’s biggest fans was an 11-year-old boy named Rusty Miller who decided he was going to author the first Star Wars quiz book and made it happen.

In a 2020 interview with Skywalking Through Neverland, Matt (née Rusty) explained, “The inspiration came when I saw a trivia book about the works of J.R.R. Tolkien, of which I was also a big fan. And since a trivia book hadn’t been done for Star Wars, I spent the Summer of 1981 coming up with over 600 questions. After finishing the book, my parents sent a manuscript to Del Rey who in turn sent it to Lucasfilm.”

cnx({

playerId: “106e33c0-3911-473c-b599-b1426db57530”,

}).render(“0270c398a82f44f49c23c16122516796”);

});

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the book almost didn’t happen in the more innocent wilds of 1982 (at least in terms of pop culture band-building). Lucasfilm saw little reason to publish the work of tweenage fan—that is until none other than George Lucas himself heard about the project and saved it from cancellation. Shortly thereafter The Jedi Master’s Quizbook debuted on the New York Times bestseller list, and according to its author sold over a million copies.

In 2025 the only copy of the Jedi Master’s Quizbook that you’re likely to find will be in the thrift store, your fave second hand online book store, or the local Friends of the Library store, which is exactly how I got my own copy. The dog-eared paperback is very well loved and once belonged to someone whose name is scrawled in pencil multiple times throughout the pages.

As I scoured through it for the first time in many years, I was blown away not just by Rusty’s extensive Star Wars knowledge but also by what the book said about how fandom, franchises, the concept of canon, and Star Wars itself has changed over the years.

Questions like “Who did Bend fend off at the Cantina?” and its answer “Snaggletooth,” the name of the character that was packaged with the Kenner toy of the character, are a great example of how some things never change. Toys have always played a massive part in determining and revealing canon. That’s something that readers, fans, and filmmakers all still deal with today. But while the struggles of creating art under capitalism are the same, the answer to Rusty’s question is different. Now Snaggletooth is nothing but the nickname of the Snivvian male named Zutton.

This was decades before the internet, so Rusty diligently explored what existed at the time: Star Wars, The Empire Strikes Back, and any info he could find about the upcoming third film, as well as the burgeoning Star Wars publishing initiatives. In another delightful time capsule, as many Star Wars lovers know, Return of the Jedi was then going to be called Revenge of the Jedi. That’s what Rusty put for his answer because the title hadn’t yet been changed due to the decision by Lucas that Jedi cannot feel or seek revenge. Hence that word was saved for decades until we got Revenge of the Sith.

That notion of the ever-shifting nature of canon and even titling is present throughout the book. But it also reminds us that despite all of that, some things never change, or at least they change enough to return back to where they started.

When Miller was collating the Jedi Master’s Quiz Book, Marvel Comics was behind the popular Star Wars comics, something Miller included and that which is a factoid that proves true in 2025. However, as someone who has lived through almost four decades of Star Wars fandom, I can tell you that hasn’t always been the case. Many of the most famous and well-known Star Wars comics for instance were published by Dark Horse. But as the tides go in and out, so do publishing trends. After the sale of Lucasfilm to Disney, Marvel—itself a new Disney subsidiary at the time—took the Star Wars comic book license back from Dark Horse, only for it to currently be shared by both publishers in the present.

It’s an unwritten rule, but in 2025 to make a Star Wars project is to make a story by committee, with decades of canon and continuity to contend with. Conversely, in The Jedi Master’s Quiz Book Miller seemed almost to be the sole holder of the canon of Star Wars, something most fans could never dream of. His dedication and commitment to a galaxy far, far away meant that for many kids growing up, they too got to open up this tome and become keepers of all the facts and canon within it. In an era before Wikipedia and the internet in general, Rusty Miller became one of the earliest in a grand tradition of fans to take canon, sort it, and define it with his own hands.

One of the most fun things about Miller’s work is that you can discover new facts or history that begin to slide into your own personal Star Wars canon. For example in Rusty’s quiz book the answer to “What is Artoo’s robot classification?” is “Thermocapsulary dehousing assister,” as that’s what he was named in the novelization of the movie. That long winded classification would soon be completely replaced with Astromech—at least until the “full” title was referenced in the 2015 Star Wars comics. There are also intriguing things to learn about what was considered canon and what would later be relegated to the non-canon world of Legends.

Although you will rarely, if ever, see Jedi Master’s Quiz Book cited as a key addition to canon now, at the time the world of Star Wars was expanding rapidly and the lore was beginning to grow. Thanks to the early interaction between the films and the novelizations, including the would-be-sequel story Splinter of the Mind’s Eye by Alan Dean Foster, and the Marvel Comics, the Expanded Universe of Star Wars had truly begun. Which would hilariously instantly cause canonical confusions, including that in the novelization of the film, X-Wing pilot Porkins was given the callsign Blue 4 when in the film he was Red 6. He wasn’t the only one either as Wedge Antilles was named Blue 2!

In a world where we couldn’t be further from the conditions in which the Jedi Masters Quiz Book came to exist, the one thing that stays the same is that fans have always been the keepers of these franchises and their facts. It’s that passion and energy that still fuels fan wiki pages and fills convention centers all year round. Thank you for being our fandom forbearer, Rusty Miller!

The post This Old Star Wars Quiz Book Shows Just How Much the Franchise Has Changed appeared first on Den of Geek.

Sustainable Banking: Dame Alison Rose’s Approach to Climate Change and Corporate Responsibility

When Dame Alison Rose assumed leadership of NatWest Group in 2019, she recognised that climate change represented not just an environmental challenge but “probably the biggest existential threat that we will face as a society.” Her response was to position the bank at the forefront of sustainable finance, implementing what she describes as “a very clear strategy on climate” that would fundamentally reshape how NatWest operates and lends.

The post Sustainable Banking: Dame Alison Rose’s Approach to Climate Change and Corporate Responsibility appeared first on Green Prophet.

The Allen Telescope Array (ATA), operated by the SETI Institute

New agreement aims to shield radio astronomy from satellite interference, but the night sky faces growing threats.

SpaceX has deployed satellites to run Starlink

The Bigger Picture: Space Junk and a Dimming Night Sky

Space junk

The post SpaceX and SETI Partner to Protect Alien-Hunting Telescopes—But What About the Rest of the Sky? appeared first on Green Prophet.

Glass Bottles May Contain More Microplastics Than Plastic or Cans, New French Study Finds

Even beverages like wine and bottled water—often seen as “cleaner” when packaged in glass—showed measurable microplastic contamination. Water in glass bottles had 4.5 particles per litre, compared to 1.6 in plastic bottles and cartons. Wine sealed with corks contained minimal microplastics.

The post Glass Bottles May Contain More Microplastics Than Plastic or Cans, New French Study Finds appeared first on Green Prophet.

The Allen Telescope Array (ATA), operated by the SETI Institute

New agreement aims to shield radio astronomy from satellite interference, but the night sky faces growing threats.

SpaceX has deployed satellites to run Starlink

The Bigger Picture: Space Junk and a Dimming Night Sky

Space junk

The post SpaceX and SETI Partner to Protect Alien-Hunting Telescopes—But What About the Rest of the Sky? appeared first on Green Prophet.

A Fox Rescuer’s Final Battle: Remembering Mikayla Raines of Save A Fox

The animal rescue world is mourning the tragic loss of Mikayla Raines, founder and executive director of Save A Fox Rescue, who died recently after what her friends and colleagues described as a lifelong struggle with mental illness. She committed suicide after experiencing online harassment. Her passing has left a powerful legacy—and painful questions—rippling through the fox rescue and wildlife rehabilitation communities.

The post A Fox Rescuer’s Final Battle: Remembering Mikayla Raines of Save A Fox appeared first on Green Prophet.

The Allen Telescope Array (ATA), operated by the SETI Institute

New agreement aims to shield radio astronomy from satellite interference, but the night sky faces growing threats.

SpaceX has deployed satellites to run Starlink

The Bigger Picture: Space Junk and a Dimming Night Sky

Space junk

The post SpaceX and SETI Partner to Protect Alien-Hunting Telescopes—But What About the Rest of the Sky? appeared first on Green Prophet.

Why Your AC Might Be Struggling—And What You Can Do About It

As heat waves push temperatures well into the triple digits across much of the U.S., homeowners are flooding HVAC companies with the same urgent question: Why isn’t my AC keeping up?

The post Why Your AC Might Be Struggling—And What You Can Do About It appeared first on Green Prophet.

The Allen Telescope Array (ATA), operated by the SETI Institute

New agreement aims to shield radio astronomy from satellite interference, but the night sky faces growing threats.

SpaceX has deployed satellites to run Starlink

The Bigger Picture: Space Junk and a Dimming Night Sky

Space junk

The post SpaceX and SETI Partner to Protect Alien-Hunting Telescopes—But What About the Rest of the Sky? appeared first on Green Prophet.

SpaceX and SETI Partner to Protect Alien-Hunting Telescopes—But What About the Rest of the Sky?

SpaceX has taken steps to address concerns, including darker satellite coatings and directional signal shielding. But critics argue that without enforceable global standards, voluntary measures may not go far enough. Meanwhile, scientists at SETI and other institutions continue developing tools to protect the last wild frontier: the cosmic spectrum.

The post SpaceX and SETI Partner to Protect Alien-Hunting Telescopes—But What About the Rest of the Sky? appeared first on Green Prophet.

The Allen Telescope Array (ATA), operated by the SETI Institute

New agreement aims to shield radio astronomy from satellite interference, but the night sky faces growing threats.

SpaceX has deployed satellites to run Starlink

The Bigger Picture: Space Junk and a Dimming Night Sky

Space junk

The post SpaceX and SETI Partner to Protect Alien-Hunting Telescopes—But What About the Rest of the Sky? appeared first on Green Prophet.

That’s Not My Burnout

Are you like me, reading about people fading away as they burn out, and feeling unable to relate? Do you feel like your feelings are invisible to the world because you’re experiencing burnout differently? When burnout starts to push down on us, our core comes through more. Beautiful, peaceful souls get quieter and fade into that distant and distracted burnout we’ve all read about. But some of us, those with fires always burning on the edges of our core, get hotter. In my heart I am fire. When I face burnout I double down, triple down, burning hotter and hotter to try to best the challenge. I don’t fade—I am engulfed in a zealous burnout.

So what on earth is a zealous burnout?

Imagine a woman determined to do it all. She has two amazing children whom she, along with her husband who is also working remotely, is homeschooling during a pandemic. She has a demanding client load at work—all of whom she loves. She gets up early to get some movement in (or often catch up on work), does dinner prep as the kids are eating breakfast, and gets to work while positioning herself near “fourth grade” to listen in as she juggles clients, tasks, and budgets. Sound like a lot? Even with a supportive team both at home and at work, it is.

Sounds like this woman has too much on her plate and needs self-care. But no, she doesn’t have time for that. In fact, she starts to feel like she’s dropping balls. Not accomplishing enough. There’s not enough of her to be here and there; she is trying to divide her mind in two all the time, all day, every day. She starts to doubt herself. And as those feelings creep in more and more, her internal narrative becomes more and more critical.

Suddenly she KNOWS what she needs to do! She should DO MORE.

This is a hard and dangerous cycle. Know why? Because once she doesn’t finish that new goal, that narrative will get worse. Suddenly she’s failing. She isn’t doing enough. SHE is not enough. She might fail, she might fail her family…so she’ll find more she should do. She doesn’t sleep as much, move as much, all in the efforts to do more. Caught in this cycle of trying to prove herself to herself, never reaching any goal. Never feeling “enough.”

So, yeah, that’s what zealous burnout looks like for me. It doesn’t happen overnight in some grand gesture but instead slowly builds over weeks and months. My burning out process looks like speeding up, not a person losing focus. I speed up and up and up…and then I just stop.

I am the one who could

It’s funny the things that shape us. Through the lens of childhood, I viewed the fears, struggles, and sacrifices of someone who had to make it all work without having enough. I was lucky that my mother was so resourceful and my father supportive; I never went without and even got an extra here or there.

Growing up, I did not feel shame when my mother paid with food stamps; in fact, I’d have likely taken on any debate on the topic, verbally eviscerating anyone who dared to criticize the disabled woman trying to make sure all our needs were met with so little. As a child, I watched the way the fear of not making those ends meet impacted people I love. As the non-disabled person in my home, I would take on many of the physical tasks because I was “the one who could” make our lives a little easier. I learned early to associate fears or uncertainty with putting more of myself into it—I am the one who can. I learned early that when something frightens me, I can double down and work harder to make it better. I can own the challenge. When people have seen this in me as an adult, I’ve been told I seem fearless, but make no mistake, I’m not. If I seem fearless, it’s because this behavior was forged from other people’s fears.

And here I am, more than 30 years later still feeling the urge to mindlessly push myself forward when faced with overwhelming tasks ahead of me, assuming that I am the one who can and therefore should. I find myself driven to prove that I can make things happen if I work longer hours, take on more responsibility, and do more.

I do not see people who struggle financially as failures, because I have seen how strong that tide can be—it pulls you along the way. I truly get that I have been privileged to be able to avoid many of the challenges that were present in my youth. That said, I am still “the one who can” who feels she should, so if I were faced with not having enough to make ends meet for my own family, I would see myself as having failed. Though I am supported and educated, most of this is due to good fortune. I will, however, allow myself the arrogance of saying I have been careful with my choices to have encouraged that luck. My identity stems from the idea that I am “the one who can” so therefore feel obligated to do the most. I can choose to stop, and with some quite literal cold water splashed in my face, I’ve made the choice to before. But that choosing to stop is not my go-to; I move forward, driven by a fear that is so a part of me that I barely notice it’s there until I’m feeling utterly worn away.

So why all the history? You see, burnout is a fickle thing. I have heard and read a lot about burnout over the years. Burnout is real. Especially now, with COVID, many of us are balancing more than we ever have before—all at once! It’s hard, and the procrastinating, the avoidance, the shutting down impacts so many amazing professionals. There are important articles that relate to what I imagine must be the majority of people out there, but not me. That’s not what my burnout looks like.

The dangerous invisibility of zealous burnout

A lot of work environments see the extra hours, extra effort, and overall focused commitment as an asset (and sometimes that’s all it is). They see someone trying to rise to challenges, not someone stuck in their fear. Many well-meaning organizations have safeguards in place to protect their teams from burnout. But in cases like this, those alarms are not always tripped, and then when the inevitable stop comes, some members of the organization feel surprised and disappointed. And sometimes maybe even betrayed.

Parents—more so mothers, statistically speaking—are praised as being so on top of it all when they can work, be involved in the after-school activities, practice self-care in the form of diet and exercise, and still meet friends for coffee or wine. During COVID many of us have binged countless streaming episodes showing how it’s so hard for the female protagonist, but she is strong and funny and can do it. It’s a “very special episode” when she breaks down, cries in the bathroom, woefully admits she needs help, and just stops for a bit. Truth is, countless people are hiding their tears or are doom-scrolling to escape. We know that the media is a lie to amuse us, but often the perception that it’s what we should strive for has penetrated much of society.

Women and burnout

I love men. And though I don’t love every man (heads up, I don’t love every woman or nonbinary person either), I think there is a beautiful spectrum of individuals who represent that particular binary gender.

That said, women are still more often at risk of burnout than their male counterparts, especially in these COVID stressed times. Mothers in the workplace feel the pressure to do all the “mom” things while giving 110%. Mothers not in the workplace feel they need to do more to “justify” their lack of traditional employment. Women who are not mothers often feel the need to do even more because they don’t have that extra pressure at home. It’s vicious and systemic and so a part of our culture that we’re often not even aware of the enormity of the pressures we put on ourselves and each other.

And there are prices beyond happiness too. Harvard Health Publishing released a study a decade ago that “uncovered strong links between women’s job stress and cardiovascular disease.” The CDC noted, “Heart disease is the leading cause of death for women in the United States, killing 299,578 women in 2017—or about 1 in every 5 female deaths.”

This relationship between work stress and health, from what I have read, is more dangerous for women than it is for their non-female counterparts.

But what if your burnout isn’t like that either?

That might not be you either. After all, each of us is so different and how we respond to stressors is too. It’s part of what makes us human. Don’t stress what burnout looks like, just learn to recognize it in yourself. Here are a few questions I sometimes ask friends if I am concerned about them.

Are you happy? This simple question should be the first thing you ask yourself. Chances are, even if you’re burning out doing all the things you love, as you approach burnout you’ll just stop taking as much joy from it all.

Do you feel empowered to say no? I have observed in myself and others that when someone is burning out, they no longer feel they can say no to things. Even those who don’t “speed up” feel pressure to say yes to not disappoint the people around them.

What are three things you’ve done for yourself? Another observance is that we all tend to stop doing things for ourselves. Anything from skipping showers and eating poorly to avoiding talking to friends. These can be red flags.

Are you making excuses? Many of us try to disregard feelings of burnout. Over and over I have heard, “It’s just crunch time,” “As soon as I do this one thing, it will all be better,” and “Well I should be able to handle this, so I’ll figure it out.” And it might really be crunch time, a single goal, and/or a skill set you need to learn. That happens—life happens. BUT if this doesn’t stop, be honest with yourself. If you’ve worked more 50-hour weeks since January than not, maybe it’s not crunch time—maybe it’s a bad situation that you’re burning out from.

Do you have a plan to stop feeling this way? If something is truly temporary and you do need to just push through, then it has an exit route with a

defined end.

Take the time to listen to yourself as you would a friend. Be honest, allow yourself to be uncomfortable, and break the thought cycles that prevent you from healing.

So now what?

What I just described is a different path to burnout, but it’s still burnout. There are well-established approaches to working through burnout:

- Get enough sleep.

- Eat healthy.

- Work out.

- Get outside.

- Take a break.

- Overall, practice self-care.

Those are hard for me because they feel like more tasks. If I’m in the burnout cycle, doing any of the above for me feels like a waste. The narrative is that if I’m already failing, why would I take care of myself when I’m dropping all those other balls? People need me, right?

If you’re deep in the cycle, your inner voice might be pretty awful by now. If you need to, tell yourself you need to take care of the person your people depend on. If your roles are pushing you toward burnout, use them to help make healing easier by justifying the time spent working on you.

To help remind myself of the airline attendant message about putting the mask on yourself first, I have come up with a few things that I do when I start feeling myself going into a zealous burnout.

Cook an elaborate meal for someone!

OK, I am a “food-focused” individual so cooking for someone is always my go-to. There are countless tales in my home of someone walking into the kitchen and turning right around and walking out when they noticed I was “chopping angrily.” But it’s more than that, and you should give it a try. Seriously. It’s the perfect go-to if you don’t feel worthy of taking time for yourself—do it for someone else. Most of us work in a digital world, so cooking can fill all of your senses and force you to be in the moment with all the ways you perceive the world. It can break you out of your head and help you gain a better perspective. In my house, I’ve been known to pick a place on the map and cook food that comes from wherever that is (thank you, Pinterest). I love cooking Indian food, as the smells are warm, the bread needs just enough kneading to keep my hands busy, and the process takes real attention for me because it’s not what I was brought up making. And in the end, we all win!

Vent like a foul-mouthed fool

Be careful with this one!

I have been making an effort to practice more gratitude over the past few years, and I recognize the true benefits of that. That said, sometimes you just gotta let it all out—even the ugly. Hell, I’m a big fan of not sugarcoating our lives, and that sometimes means that to get past the big pile of poop, you’re gonna wanna complain about it a bit.

When that is what’s needed, turn to a trusted friend and allow yourself some pure verbal diarrhea, saying all the things that are bothering you. You need to trust this friend not to judge, to see your pain, and, most importantly, to tell you to remove your cranium from your own rectal cavity. Seriously, it’s about getting a reality check here! One of the things I admire the most about my husband (though often after the fact) is his ability to break things down to their simplest. “We’re spending our lives together, of course you’re going to disappoint me from time to time, so get over it” has been his way of speaking his dedication, love, and acceptance of me—and I could not be more grateful. It also, of course, has meant that I needed to remove my head from that rectal cavity. So, again, usually those moments are appreciated in hindsight.

Pick up a book!

There are many books out there that aren’t so much self-help as they are people just like you sharing their stories and how they’ve come to find greater balance. Maybe you’ll find something that speaks to you. Titles that have stood out to me include:

- Thrive by Arianna Huffington

- Tools of Titans by Tim Ferriss

- Girl, Stop Apologizing by Rachel Hollis

- Dare to Lead by Brené Brown

Or, another tactic I love to employ is to read or listen to a book that has NOTHING to do with my work-life balance. I’ve read the following books and found they helped balance me out because my mind was pondering their interesting topics instead of running in circles:

- The Drunken Botanist by Amy Stewart

- Superlife by Darin Olien

- A Brief History of Everyone Who Ever Lived by Adam Rutherford

- Gaia’s Garden by Toby Hemenway

If you’re not into reading, pick up a topic on YouTube or choose a podcast to subscribe to. I’ve watched countless permaculture and gardening topics in addition to how to raise chickens and ducks. For the record, I do not have a particularly large food garden, nor do I own livestock of any kind…yet. I just find the topic interesting, and it has nothing to do with any aspect of my life that needs anything from me.

Forgive yourself

You are never going to be perfect—hell, it would be boring if you were. It’s OK to be broken and flawed. It’s human to be tired and sad and worried. It’s OK to not do it all. It’s scary to be imperfect, but you cannot be brave if nothing were scary.

This last one is the most important: allow yourself permission to NOT do it all. You never promised to be everything to everyone at all times. We are more powerful than the fears that drive us.

This is hard. It is hard for me. It’s what’s driven me to write this—that it’s OK to stop. It’s OK that your unhealthy habit that might even benefit those around you needs to end. You can still be successful in life.

I recently read that we are all writing our eulogy in how we live. Knowing that your professional accomplishments won’t be mentioned in that speech, what will yours say? What do you want it to say?

Look, I get that none of these ideas will “fix it,” and that’s not their purpose. None of us are in control of our surroundings, only how we respond to them. These suggestions are to help stop the spiral effect so that you are empowered to address the underlying issues and choose your response. They are things that work for me most of the time. Maybe they’ll work for you.

Does this sound familiar?

If this sounds familiar, it’s not just you. Don’t let your negative self-talk tell you that you “even burn out wrong.” It’s not wrong. Even if rooted in fear like my own drivers, I believe that this need to do more comes from a place of love, determination, motivation, and other wonderful attributes that make you the amazing person you are. We’re going to be OK, ya know. The lives that unfold before us might never look like that story in our head—that idea of “perfect” or “done” we’re looking for, but that’s OK. Really, when we stop and look around, usually the only eyes that judge us are in the mirror.

Do you remember that Winnie the Pooh sketch that had Pooh eat so much at Rabbit’s house that his buttocks couldn’t fit through the door? Well, I already associate a lot with Rabbit, so it came as no surprise when he abruptly declared that this was unacceptable. But do you recall what happened next? He put a shelf across poor Pooh’s ankles and decorations on his back, and made the best of the big butt in his kitchen.

At the end of the day we are resourceful and know that we are able to push ourselves if we need to—even when we are tired to our core or have a big butt of fluff ‘n’ stuff in our room. None of us has to be afraid, as we can manage any obstacle put in front of us. And maybe that means we will need to redefine success to allow space for being uncomfortably human, but that doesn’t really sound so bad either.

So, wherever you are right now, please breathe. Do what you need to do to get out of your head. Forgive and take care.

Asynchronous Design Critique: Giving Feedback

Feedback, in whichever form it takes, and whatever it may be called, is one of the most effective soft skills that we have at our disposal to collaboratively get our designs to a better place while growing our own skills and perspectives.

Feedback is also one of the most underestimated tools, and often by assuming that we’re already good at it, we settle, forgetting that it’s a skill that can be trained, grown, and improved. Poor feedback can create confusion in projects, bring down morale, and affect trust and team collaboration over the long term. Quality feedback can be a transformative force.

Practicing our skills is surely a good way to improve, but the learning gets even faster when it’s paired with a good foundation that channels and focuses the practice. What are some foundational aspects of giving good feedback? And how can feedback be adjusted for remote and distributed work environments?

On the web, we can identify a long tradition of asynchronous feedback: from the early days of open source, code was shared and discussed on mailing lists. Today, developers engage on pull requests, designers comment in their favorite design tools, project managers and scrum masters exchange ideas on tickets, and so on.

Design critique is often the name used for a type of feedback that’s provided to make our work better, collaboratively. So it shares a lot of the principles with feedback in general, but it also has some differences.

The content

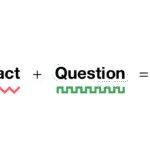

The foundation of every good critique is the feedback’s content, so that’s where we need to start. There are many models that you can use to shape your content. The one that I personally like best—because it’s clear and actionable—is this one from Lara Hogan.

While this equation is generally used to give feedback to people, it also fits really well in a design critique because it ultimately answers some of the core questions that we work on: What? Where? Why? How? Imagine that you’re giving some feedback about some design work that spans multiple screens, like an onboarding flow: there are some pages shown, a flow blueprint, and an outline of the decisions made. You spot something that could be improved. If you keep the three elements of the equation in mind, you’ll have a mental model that can help you be more precise and effective.

Here is a comment that could be given as a part of some feedback, and it might look reasonable at a first glance: it seems to superficially fulfill the elements in the equation. But does it?

Not sure about the buttons’ styles and hierarchy—it feels off. Can you change them?

Observation for design feedback doesn’t just mean pointing out which part of the interface your feedback refers to, but it also refers to offering a perspective that’s as specific as possible. Are you providing the user’s perspective? Your expert perspective? A business perspective? The project manager’s perspective? A first-time user’s perspective?

When I see these two buttons, I expect one to go forward and one to go back.

Impact is about the why. Just pointing out a UI element might sometimes be enough if the issue may be obvious, but more often than not, you should add an explanation of what you’re pointing out.

When I see these two buttons, I expect one to go forward and one to go back. But this is the only screen where this happens, as before we just used a single button and an “×” to close. This seems to be breaking the consistency in the flow.

The question approach is meant to provide open guidance by eliciting the critical thinking in the designer receiving the feedback. Notably, in Lara’s equation she provides a second approach: request, which instead provides guidance toward a specific solution. While that’s a viable option for feedback in general, for design critiques, in my experience, defaulting to the question approach usually reaches the best solutions because designers are generally more comfortable in being given an open space to explore.

The difference between the two can be exemplified with, for the question approach:

When I see these two buttons, I expect one to go forward and one to go back. But this is the only screen where this happens, as before we just used a single button and an “×” to close. This seems to be breaking the consistency in the flow. Would it make sense to unify them?

Or, for the request approach:

When I see these two buttons, I expect one to go forward and one to go back. But this is the only screen where this happens, as before we just used a single button and an “×” to close. This seems to be breaking the consistency in the flow. Let’s make sure that all screens have the same pair of forward and back buttons.

At this point in some situations, it might be useful to integrate with an extra why: why you consider the given suggestion to be better.

When I see these two buttons, I expect one to go forward and one to go back. But this is the only screen where this happens, as before we just used a single button and an “×” to close. This seems to be breaking the consistency in the flow. Let’s make sure that all screens have the same two forward and back buttons so that users don’t get confused.

Choosing the question approach or the request approach can also at times be a matter of personal preference. A while ago, I was putting a lot of effort into improving my feedback: I did rounds of anonymous feedback, and I reviewed feedback with other people. After a few rounds of this work and a year later, I got a positive response: my feedback came across as effective and grounded. Until I changed teams. To my shock, my next round of feedback from one specific person wasn’t that great. The reason is that I had previously tried not to be prescriptive in my advice—because the people who I was previously working with preferred the open-ended question format over the request style of suggestions. But now in this other team, there was one person who instead preferred specific guidance. So I adapted my feedback for them to include requests.

One comment that I heard come up a few times is that this kind of feedback is quite long, and it doesn’t seem very efficient. No… but also yes. Let’s explore both sides.

No, this style of feedback is actually efficient because the length here is a byproduct of clarity, and spending time giving this kind of feedback can provide exactly enough information for a good fix. Also if we zoom out, it can reduce future back-and-forth conversations and misunderstandings, improving the overall efficiency and effectiveness of collaboration beyond the single comment. Imagine that in the example above the feedback were instead just, “Let’s make sure that all screens have the same two forward and back buttons.” The designer receiving this feedback wouldn’t have much to go by, so they might just apply the change. In later iterations, the interface might change or they might introduce new features—and maybe that change might not make sense anymore. Without the why, the designer might imagine that the change is about consistency… but what if it wasn’t? So there could now be an underlying concern that changing the buttons would be perceived as a regression.

Yes, this style of feedback is not always efficient because the points in some comments don’t always need to be exhaustive, sometimes because certain changes may be obvious (“The font used doesn’t follow our guidelines”) and sometimes because the team may have a lot of internal knowledge such that some of the whys may be implied.

So the equation above isn’t meant to suggest a strict template for feedback but a mnemonic to reflect and improve the practice. Even after years of active work on my critiques, I still from time to time go back to this formula and reflect on whether what I just wrote is effective.

The tone

Well-grounded content is the foundation of feedback, but that’s not really enough. The soft skills of the person who’s providing the critique can multiply the likelihood that the feedback will be well received and understood. Tone alone can make the difference between content that’s rejected or welcomed, and it’s been demonstrated that only positive feedback creates sustained change in people.

Since our goal is to be understood and to have a positive working environment, tone is essential to work on. Over the years, I’ve tried to summarize the required soft skills in a formula that mirrors the one for content: the receptivity equation.

Respectful feedback comes across as grounded, solid, and constructive. It’s the kind of feedback that, whether it’s positive or negative, is perceived as useful and fair.

Timing refers to when the feedback happens. To-the-point feedback doesn’t have much hope of being well received if it’s given at the wrong time. Questioning the entire high-level information architecture of a new feature when it’s about to ship might still be relevant if that questioning highlights a major blocker that nobody saw, but it’s way more likely that those concerns will have to wait for a later rework. So in general, attune your feedback to the stage of the project. Early iteration? Late iteration? Polishing work in progress? These all have different needs. The right timing will make it more likely that your feedback will be well received.

Attitude is the equivalent of intent, and in the context of person-to-person feedback, it can be referred to as radical candor. That means checking before we write to see whether what we have in mind will truly help the person and make the project better overall. This might be a hard reflection at times because maybe we don’t want to admit that we don’t really appreciate that person. Hopefully that’s not the case, but that can happen, and that’s okay. Acknowledging and owning that can help you make up for that: how would I write if I really cared about them? How can I avoid being passive aggressive? How can I be more constructive?

Form is relevant especially in a diverse and cross-cultural work environments because having great content, perfect timing, and the right attitude might not come across if the way that we write creates misunderstandings. There might be many reasons for this: sometimes certain words might trigger specific reactions; sometimes nonnative speakers might not understand all the nuances of some sentences; sometimes our brains might just be different and we might perceive the world differently—neurodiversity must be taken into consideration. Whatever the reason, it’s important to review not just what we write but how.

A few years back, I was asking for some feedback on how I give feedback. I received some good advice but also a comment that surprised me. They pointed out that when I wrote “Oh, […],” I made them feel stupid. That wasn’t my intent! I felt really bad, and I just realized that I provided feedback to them for months, and every time I might have made them feel stupid. I was horrified… but also thankful. I made a quick fix: I added “oh” in my list of replaced words (your choice between: macOS’s text replacement, aText, TextExpander, or others) so that when I typed “oh,” it was instantly deleted.

Something to highlight because it’s quite frequent—especially in teams that have a strong group spirit—is that people tend to beat around the bush. It’s important to remember here that a positive attitude doesn’t mean going light on the feedback—it just means that even when you provide hard, difficult, or challenging feedback, you do so in a way that’s respectful and constructive. The nicest thing that you can do for someone is to help them grow.

We have a great advantage in giving feedback in written form: it can be reviewed by another person who isn’t directly involved, which can help to reduce or remove any bias that might be there. I found that the best, most insightful moments for me have happened when I’ve shared a comment and I’ve asked someone who I highly trusted, “How does this sound?,” “How can I do it better,” and even “How would you have written it?”—and I’ve learned a lot by seeing the two versions side by side.

The format

Asynchronous feedback also has a major inherent advantage: we can take more time to refine what we’ve written to make sure that it fulfills two main goals: the clarity of communication and the actionability of the suggestions.

Let’s imagine that someone shared a design iteration for a project. You are reviewing it and leaving a comment. There are many ways to do this, and of course context matters, but let’s try to think about some elements that may be useful to consider.

In terms of clarity, start by grounding the critique that you’re about to give by providing context. Specifically, this means describing where you’re coming from: do you have a deep knowledge of the project, or is this the first time that you’re seeing it? Are you coming from a high-level perspective, or are you figuring out the details? Are there regressions? Which user’s perspective are you taking when providing your feedback? Is the design iteration at a point where it would be okay to ship this, or are there major things that need to be addressed first?

Providing context is helpful even if you’re sharing feedback within a team that already has some information on the project. And context is absolutely essential when giving cross-team feedback. If I were to review a design that might be indirectly related to my work, and if I had no knowledge about how the project arrived at that point, I would say so, highlighting my take as external.

We often focus on the negatives, trying to outline all the things that could be done better. That’s of course important, but it’s just as important—if not more—to focus on the positives, especially if you saw progress from the previous iteration. This might seem superfluous, but it’s important to keep in mind that design is a discipline where there are hundreds of possible solutions for every problem. So pointing out that the design solution that was chosen is good and explaining why it’s good has two major benefits: it confirms that the approach taken was solid, and it helps to ground your negative feedback. In the longer term, sharing positive feedback can help prevent regressions on things that are going well because those things will have been highlighted as important. As a bonus, positive feedback can also help reduce impostor syndrome.

There’s one powerful approach that combines both context and a focus on the positives: frame how the design is better than the status quo (compared to a previous iteration, competitors, or benchmarks) and why, and then on that foundation, you can add what could be improved. This is powerful because there’s a big difference between a critique that’s for a design that’s already in good shape and a critique that’s for a design that isn’t quite there yet.

Another way that you can improve your feedback is to depersonalize the feedback: the comments should always be about the work, never about the person who made it. It’s “This button isn’t well aligned” versus “You haven’t aligned this button well.” This is very easy to change in your writing by reviewing it just before sending.

In terms of actionability, one of the best approaches to help the designer who’s reading through your feedback is to split it into bullet points or paragraphs, which are easier to review and analyze one by one. For longer pieces of feedback, you might also consider splitting it into sections or even across multiple comments. Of course, adding screenshots or signifying markers of the specific part of the interface you’re referring to can also be especially useful.

One approach that I’ve personally used effectively in some contexts is to enhance the bullet points with four markers using emojis. So a red square 🟥 means that it’s something that I consider blocking; a yellow diamond 🔶 is something that I can be convinced otherwise, but it seems to me that it should be changed; and a green circle 🟢 is a detailed, positive confirmation. I also use a blue spiral 🌀 for either something that I’m not sure about, an exploration, an open alternative, or just a note. But I’d use this approach only on teams where I’ve already established a good level of trust because if it happens that I have to deliver a lot of red squares, the impact could be quite demoralizing, and I’d reframe how I’d communicate that a bit.

Let’s see how this would work by reusing the example that we used earlier as the first bullet point in this list:

- 🔶 Navigation—When I see these two buttons, I expect one to go forward and one to go back. But this is the only screen where this happens, as before we just used a single button and an “×” to close. This seems to be breaking the consistency in the flow. Let’s make sure that all screens have the same two forward and back buttons so that users don’t get confused.

- 🟢 Overall—I think the page is solid, and this is good enough to be our release candidate for a version 1.0.

- 🟢 Metrics—Good improvement in the buttons on the metrics area; the improved contrast and new focus style make them more accessible.

- 🟥 Button Style—Using the green accent in this context creates the impression that it’s a positive action because green is usually perceived as a confirmation color. Do we need to explore a different color?

- 🔶Tiles—Given the number of items on the page, and the overall page hierarchy, it seems to me that the tiles shouldn’t be using the Subtitle 1 style but the Subtitle 2 style. This will keep the visual hierarchy more consistent.

- 🌀 Background—Using a light texture works well, but I wonder whether it adds too much noise in this kind of page. What is the thinking in using that?

What about giving feedback directly in Figma or another design tool that allows in-place feedback? In general, I find these difficult to use because they hide discussions and they’re harder to track, but in the right context, they can be very effective. Just make sure that each of the comments is separate so that it’s easier to match each discussion to a single task, similar to the idea of splitting mentioned above.

One final note: say the obvious. Sometimes we might feel that something is obviously good or obviously wrong, and so we don’t say it. Or sometimes we might have a doubt that we don’t express because the question might sound stupid. Say it—that’s okay. You might have to reword it a little bit to make the reader feel more comfortable, but don’t hold it back. Good feedback is transparent, even when it may be obvious.

There’s another advantage of asynchronous feedback: written feedback automatically tracks decisions. Especially in large projects, “Why did we do this?” could be a question that pops up from time to time, and there’s nothing better than open, transparent discussions that can be reviewed at any time. For this reason, I recommend using software that saves these discussions, without hiding them once they are resolved.

Content, tone, and format. Each one of these subjects provides a useful model, but working to improve eight areas—observation, impact, question, timing, attitude, form, clarity, and actionability—is a lot of work to put in all at once. One effective approach is to take them one by one: first identify the area that you lack the most (either from your perspective or from feedback from others) and start there. Then the second, then the third, and so on. At first you’ll have to put in extra time for every piece of feedback that you give, but after a while, it’ll become second nature, and your impact on the work will multiply.

Thanks to Brie Anne Demkiw and Mike Shelton for reviewing the first draft of this article.

Asynchronous Design Critique: Getting Feedback

“Any comment?” is probably one of the worst ways to ask for feedback. It’s vague and open ended, and it doesn’t provide any indication of what we’re looking for. Getting good feedback starts earlier than we might expect: it starts with the request.

It might seem counterintuitive to start the process of receiving feedback with a question, but that makes sense if we realize that getting feedback can be thought of as a form of design research. In the same way that we wouldn’t do any research without the right questions to get the insights that we need, the best way to ask for feedback is also to craft sharp questions.

Design critique is not a one-shot process. Sure, any good feedback workflow continues until the project is finished, but this is particularly true for design because design work continues iteration after iteration, from a high level to the finest details. Each level needs its own set of questions.

And finally, as with any good research, we need to review what we got back, get to the core of its insights, and take action. Question, iteration, and review. Let’s look at each of those.

The question

Being open to feedback is essential, but we need to be precise about what we’re looking for. Just saying “Any comment?”, “What do you think?”, or “I’d love to get your opinion” at the end of a presentation—whether it’s in person, over video, or through a written post—is likely to get a number of varied opinions or, even worse, get everyone to follow the direction of the first person who speaks up. And then… we get frustrated because vague questions like those can turn a high-level flows review into people instead commenting on the borders of buttons. Which might be a hearty topic, so it might be hard at that point to redirect the team to the subject that you had wanted to focus on.

But how do we get into this situation? It’s a mix of factors. One is that we don’t usually consider asking as a part of the feedback process. Another is how natural it is to just leave the question implied, expecting the others to be on the same page. Another is that in nonprofessional discussions, there’s often no need to be that precise. In short, we tend to underestimate the importance of the questions, so we don’t work on improving them.

The act of asking good questions guides and focuses the critique. It’s also a form of consent: it makes it clear that you’re open to comments and what kind of comments you’d like to get. It puts people in the right mental state, especially in situations when they weren’t expecting to give feedback.

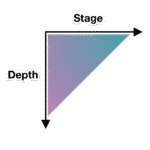

There isn’t a single best way to ask for feedback. It just needs to be specific, and specificity can take many shapes. A model for design critique that I’ve found particularly useful in my coaching is the one of stage versus depth.

“Stage” refers to each of the steps of the process—in our case, the design process. In progressing from user research to the final design, the kind of feedback evolves. But within a single step, one might still review whether some assumptions are correct and whether there’s been a proper translation of the amassed feedback into updated designs as the project has evolved. A starting point for potential questions could derive from the layers of user experience. What do you want to know: Project objectives? User needs? Functionality? Content? Interaction design? Information architecture? UI design? Navigation design? Visual design? Branding?

Here’re a few example questions that are precise and to the point that refer to different layers:

- Functionality: Is automating account creation desirable?

- Interaction design: Take a look through the updated flow and let me know whether you see any steps or error states that I might’ve missed.

- Information architecture: We have two competing bits of information on this page. Is the structure effective in communicating them both?

- UI design: What are your thoughts on the error counter at the top of the page that makes sure that you see the next error, even if the error is out of the viewport?

- Navigation design: From research, we identified these second-level navigation items, but once you’re on the page, the list feels too long and hard to navigate. Are there any suggestions to address this?

- Visual design: Are the sticky notifications in the bottom-right corner visible enough?

The other axis of specificity is about how deep you’d like to go on what’s being presented. For example, we might have introduced a new end-to-end flow, but there was a specific view that you found particularly challenging and you’d like a detailed review of that. This can be especially useful from one iteration to the next where it’s important to highlight the parts that have changed.

There are other things that we can consider when we want to achieve more specific—and more effective—questions.

A simple trick is to remove generic qualifiers from your questions like “good,” “well,” “nice,” “bad,” “okay,” and “cool.” For example, asking, “When the block opens and the buttons appear, is this interaction good?” might look specific, but you can spot the “good” qualifier, and convert it to an even better question: “When the block opens and the buttons appear, is it clear what the next action is?”

Sometimes we actually do want broad feedback. That’s rare, but it can happen. In that sense, you might still make it explicit that you’re looking for a wide range of opinions, whether at a high level or with details. Or maybe just say, “At first glance, what do you think?” so that it’s clear that what you’re asking is open ended but focused on someone’s impression after their first five seconds of looking at it.

Sometimes the project is particularly expansive, and some areas may have already been explored in detail. In these situations, it might be useful to explicitly say that some parts are already locked in and aren’t open to feedback. It’s not something that I’d recommend in general, but I’ve found it useful to avoid falling again into rabbit holes of the sort that might lead to further refinement but aren’t what’s most important right now.

Asking specific questions can completely change the quality of the feedback that you receive. People with less refined critique skills will now be able to offer more actionable feedback, and even expert designers will welcome the clarity and efficiency that comes from focusing only on what’s needed. It can save a lot of time and frustration.

The iteration

Design iterations are probably the most visible part of the design work, and they provide a natural checkpoint for feedback. Yet a lot of design tools with inline commenting tend to show changes as a single fluid stream in the same file, and those types of design tools make conversations disappear once they’re resolved, update shared UI components automatically, and compel designs to always show the latest version—unless these would-be helpful features were to be manually turned off. The implied goal that these design tools seem to have is to arrive at just one final copy with all discussions closed, probably because they inherited patterns from how written documents are collaboratively edited. That’s probably not the best way to approach design critiques, but even if I don’t want to be too prescriptive here: that could work for some teams.

The asynchronous design-critique approach that I find most effective is to create explicit checkpoints for discussion. I’m going to use the term iteration post for this. It refers to a write-up or presentation of the design iteration followed by a discussion thread of some kind. Any platform that can accommodate this structure can use this. By the way, when I refer to a “write-up or presentation,” I’m including video recordings or other media too: as long as it’s asynchronous, it works.

Using iteration posts has many advantages:

- It creates a rhythm in the design work so that the designer can review feedback from each iteration and prepare for the next.

- It makes decisions visible for future review, and conversations are likewise always available.

- It creates a record of how the design changed over time.

- Depending on the tool, it might also make it easier to collect feedback and act on it.

These posts of course don’t mean that no other feedback approach should be used, just that iteration posts could be the primary rhythm for a remote design team to use. And other feedback approaches (such as live critique, pair designing, or inline comments) can build from there.

I don’t think there’s a standard format for iteration posts. But there are a few high-level elements that make sense to include as a baseline:

- The goal

- The design

- The list of changes

- The questions

Each project is likely to have a goal, and hopefully it’s something that’s already been summarized in a single sentence somewhere else, such as the client brief, the product manager’s outline, or the project owner’s request. So this is something that I’d repeat in every iteration post—literally copy and pasting it. The idea is to provide context and to repeat what’s essential to make each iteration post complete so that there’s no need to find information spread across multiple posts. If I want to know about the latest design, the latest iteration post will have all that I need.

This copy-and-paste part introduces another relevant concept: alignment comes from repetition. So having posts that repeat information is actually very effective toward making sure that everyone is on the same page.

The design is then the actual series of information-architecture outlines, diagrams, flows, maps, wireframes, screens, visuals, and any other kind of design work that’s been done. In short, it’s any design artifact. For the final stages of work, I prefer the term blueprint to emphasize that I’ll be showing full flows instead of individual screens to make it easier to understand the bigger picture.

It can also be useful to label the artifacts with clear titles because that can make it easier to refer to them. Write the post in a way that helps people understand the work. It’s not too different from organizing a good live presentation.

For an efficient discussion, you should also include a bullet list of the changes from the previous iteration to let people focus on what’s new, which can be especially useful for larger pieces of work where keeping track, iteration after iteration, could become a challenge.

And finally, as noted earlier, it’s essential that you include a list of the questions to drive the design critique in the direction you want. Doing this as a numbered list can also help make it easier to refer to each question by its number.

Not all iterations are the same. Earlier iterations don’t need to be as tightly focused—they can be more exploratory and experimental, maybe even breaking some of the design-language guidelines to see what’s possible. Then later, the iterations start settling on a solution and refining it until the design process reaches its end and the feature ships.

I want to highlight that even if these iteration posts are written and conceived as checkpoints, by no means do they need to be exhaustive. A post might be a draft—just a concept to get a conversation going—or it could be a cumulative list of each feature that was added over the course of each iteration until the full picture is done.

Over time, I also started using specific labels for incremental iterations: i1, i2, i3, and so on. This might look like a minor labelling tip, but it can help in multiple ways:

- Unique—It’s a clear unique marker. Within each project, one can easily say, “This was discussed in i4,” and everyone knows where they can go to review things.

- Unassuming—It works like versions (such as v1, v2, and v3) but in contrast, versions create the impression of something that’s big, exhaustive, and complete. Iterations must be able to be exploratory, incomplete, partial.

- Future proof—It resolves the “final” naming problem that you can run into with versions. No more files named “final final complete no-really-its-done.” Within each project, the largest number always represents the latest iteration.

To mark when a design is complete enough to be worked on, even if there might be some bits still in need of attention and in turn more iterations needed, the wording release candidate (RC) could be used to describe it: “with i8, we reached RC” or “i12 is an RC.”

The review

What usually happens during a design critique is an open discussion, with a back and forth between people that can be very productive. This approach is particularly effective during live, synchronous feedback. But when we work asynchronously, it’s more effective to use a different approach: we can shift to a user-research mindset. Written feedback from teammates, stakeholders, or others can be treated as if it were the result of user interviews and surveys, and we can analyze it accordingly.

This shift has some major benefits that make asynchronous feedback particularly effective, especially around these friction points:

- It removes the pressure to reply to everyone.

- It reduces the frustration from swoop-by comments.

- It lessens our personal stake.

The first friction point is feeling a pressure to reply to every single comment. Sometimes we write the iteration post, and we get replies from our team. It’s just a few of them, it’s easy, and it doesn’t feel like a problem. But other times, some solutions might require more in-depth discussions, and the amount of replies can quickly increase, which can create a tension between trying to be a good team player by replying to everyone and doing the next design iteration. This might be especially true if the person who’s replying is a stakeholder or someone directly involved in the project who we feel that we need to listen to. We need to accept that this pressure is absolutely normal, and it’s human nature to try to accommodate people who we care about. Sometimes replying to all comments can be effective, but if we treat a design critique more like user research, we realize that we don’t have to reply to every comment, and in asynchronous spaces, there are alternatives:

- One is to let the next iteration speak for itself. When the design evolves and we post a follow-up iteration, that’s the reply. You might tag all the people who were involved in the previous discussion, but even that’s a choice, not a requirement.

- Another is to briefly reply to acknowledge each comment, such as “Understood. Thank you,” “Good points—I’ll review,” or “Thanks. I’ll include these in the next iteration.” In some cases, this could also be just a single top-level comment along the lines of “Thanks for all the feedback everyone—the next iteration is coming soon!”

- Another is to provide a quick summary of the comments before moving on. Depending on your workflow, this can be particularly useful as it can provide a simplified checklist that you can then use for the next iteration.

The second friction point is the swoop-by comment, which is the kind of feedback that comes from someone outside the project or team who might not be aware of the context, restrictions, decisions, or requirements—or of the previous iterations’ discussions. On their side, there’s something that one can hope that they might learn: they could start to acknowledge that they’re doing this and they could be more conscious in outlining where they’re coming from. Swoop-by comments often trigger the simple thought “We’ve already discussed this…”, and it can be frustrating to have to repeat the same reply over and over.

Let’s begin by acknowledging again that there’s no need to reply to every comment. If, however, replying to a previously litigated point might be useful, a short reply with a link to the previous discussion for extra details is usually enough. Remember, alignment comes from repetition, so it’s okay to repeat things sometimes!

Swoop-by commenting can still be useful for two reasons: they might point out something that still isn’t clear, and they also have the potential to stand in for the point of view of a user who’s seeing the design for the first time. Sure, you’ll still be frustrated, but that might at least help in dealing with it.

The third friction point is the personal stake we could have with the design, which could make us feel defensive if the review were to feel more like a discussion. Treating feedback as user research helps us create a healthy distance between the people giving us feedback and our ego (because yes, even if we don’t want to admit it, it’s there). And ultimately, treating everything in aggregated form allows us to better prioritize our work.

Always remember that while you need to listen to stakeholders, project owners, and specific advice, you don’t have to accept every piece of feedback. You have to analyze it and make a decision that you can justify, but sometimes “no” is the right answer.

As the designer leading the project, you’re in charge of that decision. Ultimately, everyone has their specialty, and as the designer, you’re the one who has the most knowledge and the most context to make the right decision. And by listening to the feedback that you’ve received, you’re making sure that it’s also the best and most balanced decision.

Thanks to Brie Anne Demkiw and Mike Shelton for reviewing the first draft of this article.