I am a creative.

I am a creative. What I do is alchemy. It is a mystery. I do not so much do it, as let it be done through me.

I am a creative. Not all creative people like this label. Not all see themselves this way. Some creative people see science in what they do. That is their truth, and I respect it. Maybe I even envy them, a little. But my process is different—my being is different.

Apologizing and qualifying in advance is a distraction. That’s what my brain does to sabotage me. I set it aside for now. I can come back later to apologize and qualify. After I’ve said what I came to say. Which is hard enough.

Except when it is easy and flows like a river of wine.

Sometimes it does come that way. Sometimes what I need to create comes in an instant. I have learned not to say it at that moment, because if you admit that sometimes the idea just comes and it is the best idea and you know it is the best idea, they think you don’t work hard enough.

Sometimes I work and work and work until the idea comes. Sometimes it comes instantly and I don’t tell anyone for three days. Sometimes I’m so excited by the idea that came instantly that I blurt it out, can’t help myself. Like a boy who found a prize in his Cracker Jacks. Sometimes I get away with this. Sometimes other people agree: yes, that is the best idea. Most times they don’t and I regret having given way to enthusiasm.

Enthusiasm is best saved for the meeting where it will make a difference. Not the casual get-together that precedes that meeting by two other meetings. Nobody knows why we have all these meetings. We keep saying we’re doing away with them, but then just finding other ways to have them. Sometimes they are even good. But other times they are a distraction from the actual work. The proportion between when meetings are useful, and when they are a pitiful distraction, varies, depending on what you do and where you do it. And who you are and how you do it. Again I digress. I am a creative. That is the theme.

Sometimes many hours of hard and patient work produce something that is barely serviceable. Sometimes I have to accept that and move on to the next project.

Don’t ask about process. I am a creative.

I am a creative. I don’t control my dreams. And I don’t control my best ideas.

I can hammer away, surround myself with facts or images, and sometimes that works. I can go for a walk, and sometimes that works. I can be making dinner and there’s a Eureka having nothing to do with sizzling oil and bubbling pots. Often I know what to do the instant I wake up. And then, almost as often, as I become conscious and part of the world again, the idea that would have saved me turns to vanishing dust in a mindless wind of oblivion. For creativity, I believe, comes from that other world. The one we enter in dreams, and perhaps, before birth and after death. But that’s for poets to wonder, and I am not a poet. I am a creative. And it’s for theologians to mass armies about in their creative world that they insist is real. But that is another digression. And a depressing one. Maybe on a much more important topic than whether I am a creative or not. But still a digression from what I came here to say.

Sometimes the process is avoidance. And agony. You know the cliché about the tortured artist? It’s true, even when the artist (and let’s put that noun in quotes) is trying to write a soft drink jingle, a callback in a tired sitcom, a budget request.

Some people who hate being called creative may be closeted creatives, but that’s between them and their gods. No offense meant. Your truth is true, too. But mine is for me.

Creatives recognize creatives.

Creatives recognize creatives like queers recognize queers, like real rappers recognize real rappers, like cons know cons. Creatives feel massive respect for creatives. We love, honor, emulate, and practically deify the great ones. To deify any human is, of course, a tragic mistake. We have been warned. We know better. We know people are just people. They squabble, they are lonely, they regret their most important decisions, they are poor and hungry, they can be cruel, they can be just as stupid as we can, because, like us, they are clay. But. But. But they make this amazing thing. They birth something that did not exist before them, and could not exist without them. They are the mothers of ideas. And I suppose, since it’s just lying there, I have to add that they are the mothers of invention. Ba dum bum! OK, that’s done. Continue.

Creatives belittle our own small achievements, because we compare them to those of the great ones. Beautiful animation! Well, I’m no Miyazaki. Now THAT is greatness. That is greatness straight from the mind of God. This half-starved little thing that I made? It more or less fell off the back of the turnip truck. And the turnips weren’t even fresh.

Creatives knows that, at best, they are Salieri. Even the creatives who are Mozart believe that.

I am a creative. I haven’t worked in advertising in 30 years, but in my nightmares, it’s my former creative directors who judge me. And they are right to do so. I am too lazy, too facile, and when it really counts, my mind goes blank. There is no pill for creative dysfunction.

I am a creative. Every deadline I make is an adventure that makes Indiana Jones look like a pensioner snoring in a deck chair. The longer I remain a creative, the faster I am when I do my work and the longer I brood and walk in circles and stare blankly before I do that work.

I am still 10 times faster than people who are not creative, or people who have only been creative a short while, or people who have only been professionally creative a short while. It’s just that, before I work 10 times as fast as they do, I spend twice as long as they do putting the work off. I am that confident in my ability to do a great job when I put my mind to it. I am that addicted to the adrenaline rush of postponement. I am still that afraid of the jump.

I am not an artist.

I am a creative. Not an artist. Though I dreamed, as a lad, of someday being that. Some of us belittle our gifts and dislike ourselves because we are not Michelangelos and Warhols. That is narcissism—but at least we aren’t in politics.

I am a creative. Though I believe in reason and science, I decide by intuition and impulse. And live with what follows—the catastrophes as well as the triumphs.

I am a creative. Every word I’ve said here will annoy other creatives, who see things differently. Ask two creatives a question, get three opinions. Our disagreement, our passion about it, and our commitment to our own truth are, at least to me, the proofs that we are creatives, no matter how we may feel about it.

I am a creative. I lament my lack of taste in the areas about which I know very little, which is to say almost all areas of human knowledge. And I trust my taste above all other things in the areas closest to my heart, or perhaps, more accurately, to my obsessions. Without my obsessions, I would probably have to spend my time looking life in the eye, and almost none of us can do that for long. Not honestly. Not really. Because much in life, if you really look at it, is unbearable.

I am a creative. I believe, as a parent believes, that when I am gone, some small good part of me will carry on in the mind of at least one other person.

Working saves me from worrying about work.

I am a creative. I live in dread of my small gift suddenly going away.

I am a creative. I am too busy making the next thing to spend too much time deeply considering that almost nothing I make will come anywhere near the greatness I comically aspire to.

I am a creative. I believe in the ultimate mystery of process. I believe in it so much, I am even fool enough to publish an essay I dictated into a tiny machine and didn’t take time to review or revise. I won’t do this often, I promise. But I did it just now, because, as afraid as I might be of your seeing through my pitiful gestures toward the beautiful, I was even more afraid of forgetting what I came to say.

There. I think I’ve said it.

Opportunities for AI in Accessibility

In reading Joe Dolson’s recent piece on the intersection of AI and accessibility, I absolutely appreciated the skepticism that he has for AI in general as well as for the ways that many have been using it. In fact, I’m very skeptical of AI myself, despite my role at Microsoft as an accessibility innovation strategist who helps run the AI for Accessibility grant program. As with any tool, AI can be used in very constructive, inclusive, and accessible ways; and it can also be used in destructive, exclusive, and harmful ones. And there are a ton of uses somewhere in the mediocre middle as well.

I’d like you to consider this a “yes… and” piece to complement Joe’s post. I’m not trying to refute any of what he’s saying but rather provide some visibility to projects and opportunities where AI can make meaningful differences for people with disabilities. To be clear, I’m not saying that there aren’t real risks or pressing issues with AI that need to be addressed—there are, and we’ve needed to address them, like, yesterday—but I want to take a little time to talk about what’s possible in hopes that we’ll get there one day.

Alternative text

Joe’s piece spends a lot of time talking about computer-vision models generating alternative text. He highlights a ton of valid issues with the current state of things. And while computer-vision models continue to improve in the quality and richness of detail in their descriptions, their results aren’t great. As he rightly points out, the current state of image analysis is pretty poor—especially for certain image types—in large part because current AI systems examine images in isolation rather than within the contexts that they’re in (which is a consequence of having separate “foundation” models for text analysis and image analysis). Today’s models aren’t trained to distinguish between images that are contextually relevant (that should probably have descriptions) and those that are purely decorative (which might not need a description) either. Still, I still think there’s potential in this space.

As Joe mentions, human-in-the-loop authoring of alt text should absolutely be a thing. And if AI can pop in to offer a starting point for alt text—even if that starting point might be a prompt saying What is this BS? That’s not right at all… Let me try to offer a starting point—I think that’s a win.

Taking things a step further, if we can specifically train a model to analyze image usage in context, it could help us more quickly identify which images are likely to be decorative and which ones likely require a description. That will help reinforce which contexts call for image descriptions and it’ll improve authors’ efficiency toward making their pages more accessible.

While complex images—like graphs and charts—are challenging to describe in any sort of succinct way (even for humans), the image example shared in the GPT4 announcement points to an interesting opportunity as well. Let’s suppose that you came across a chart whose description was simply the title of the chart and the kind of visualization it was, such as: Pie chart comparing smartphone usage to feature phone usage among US households making under $30,000 a year. (That would be a pretty awful alt text for a chart since that would tend to leave many questions about the data unanswered, but then again, let’s suppose that that was the description that was in place.) If your browser knew that that image was a pie chart (because an onboard model concluded this), imagine a world where users could ask questions like these about the graphic:

- Do more people use smartphones or feature phones?

- How many more?

- Is there a group of people that don’t fall into either of these buckets?

- How many is that?

Setting aside the realities of large language model (LLM) hallucinations—where a model just makes up plausible-sounding “facts”—for a moment, the opportunity to learn more about images and data in this way could be revolutionary for blind and low-vision folks as well as for people with various forms of color blindness, cognitive disabilities, and so on. It could also be useful in educational contexts to help people who can see these charts, as is, to understand the data in the charts.

Taking things a step further: What if you could ask your browser to simplify a complex chart? What if you could ask it to isolate a single line on a line graph? What if you could ask your browser to transpose the colors of the different lines to work better for form of color blindness you have? What if you could ask it to swap colors for patterns? Given these tools’ chat-based interfaces and our existing ability to manipulate images in today’s AI tools, that seems like a possibility.

Now imagine a purpose-built model that could extract the information from that chart and convert it to another format. For example, perhaps it could turn that pie chart (or better yet, a series of pie charts) into more accessible (and useful) formats, like spreadsheets. That would be amazing!

Matching algorithms

Safiya Umoja Noble absolutely hit the nail on the head when she titled her book Algorithms of Oppression. While her book was focused on the ways that search engines reinforce racism, I think that it’s equally true that all computer models have the potential to amplify conflict, bias, and intolerance. Whether it’s Twitter always showing you the latest tweet from a bored billionaire, YouTube sending us into a Q-hole, or Instagram warping our ideas of what natural bodies look like, we know that poorly authored and maintained algorithms are incredibly harmful. A lot of this stems from a lack of diversity among the people who shape and build them. When these platforms are built with inclusively baked in, however, there’s real potential for algorithm development to help people with disabilities.

Take Mentra, for example. They are an employment network for neurodivergent people. They use an algorithm to match job seekers with potential employers based on over 75 data points. On the job-seeker side of things, it considers each candidate’s strengths, their necessary and preferred workplace accommodations, environmental sensitivities, and so on. On the employer side, it considers each work environment, communication factors related to each job, and the like. As a company run by neurodivergent folks, Mentra made the decision to flip the script when it came to typical employment sites. They use their algorithm to propose available candidates to companies, who can then connect with job seekers that they are interested in; reducing the emotional and physical labor on the job-seeker side of things.

When more people with disabilities are involved in the creation of algorithms, that can reduce the chances that these algorithms will inflict harm on their communities. That’s why diverse teams are so important.

Imagine that a social media company’s recommendation engine was tuned to analyze who you’re following and if it was tuned to prioritize follow recommendations for people who talked about similar things but who were different in some key ways from your existing sphere of influence. For example, if you were to follow a bunch of nondisabled white male academics who talk about AI, it could suggest that you follow academics who are disabled or aren’t white or aren’t male who also talk about AI. If you took its recommendations, perhaps you’d get a more holistic and nuanced understanding of what’s happening in the AI field. These same systems should also use their understanding of biases about particular communities—including, for instance, the disability community—to make sure that they aren’t recommending any of their users follow accounts that perpetuate biases against (or, worse, spewing hate toward) those groups.

Other ways that AI can helps people with disabilities

If I weren’t trying to put this together between other tasks, I’m sure that I could go on and on, providing all kinds of examples of how AI could be used to help people with disabilities, but I’m going to make this last section into a bit of a lightning round. In no particular order:

- Voice preservation. You may have seen the VALL-E paper or Apple’s Global Accessibility Awareness Day announcement or you may be familiar with the voice-preservation offerings from Microsoft, Acapela, or others. It’s possible to train an AI model to replicate your voice, which can be a tremendous boon for people who have ALS (Lou Gehrig’s disease) or motor-neuron disease or other medical conditions that can lead to an inability to talk. This is, of course, the same tech that can also be used to create audio deepfakes, so it’s something that we need to approach responsibly, but the tech has truly transformative potential.

- Voice recognition. Researchers like those in the Speech Accessibility Project are paying people with disabilities for their help in collecting recordings of people with atypical speech. As I type, they are actively recruiting people with Parkinson’s and related conditions, and they have plans to expand this to other conditions as the project progresses. This research will result in more inclusive data sets that will let more people with disabilities use voice assistants, dictation software, and voice-response services as well as control their computers and other devices more easily, using only their voice.

- Text transformation. The current generation of LLMs is quite capable of adjusting existing text content without injecting hallucinations. This is hugely empowering for people with cognitive disabilities who may benefit from text summaries or simplified versions of text or even text that’s prepped for Bionic Reading.

The importance of diverse teams and data

We need to recognize that our differences matter. Our lived experiences are influenced by the intersections of the identities that we exist in. These lived experiences—with all their complexities (and joys and pain)—are valuable inputs to the software, services, and societies that we shape. Our differences need to be represented in the data that we use to train new models, and the folks who contribute that valuable information need to be compensated for sharing it with us. Inclusive data sets yield more robust models that foster more equitable outcomes.

Want a model that doesn’t demean or patronize or objectify people with disabilities? Make sure that you have content about disabilities that’s authored by people with a range of disabilities, and make sure that that’s well represented in the training data.

Want a model that doesn’t use ableist language? You may be able to use existing data sets to build a filter that can intercept and remediate ableist language before it reaches readers. That being said, when it comes to sensitivity reading, AI models won’t be replacing human copy editors anytime soon.

Want a coding copilot that gives you accessible recommendations from the jump? Train it on code that you know to be accessible.

I have no doubt that AI can and will harm people… today, tomorrow, and well into the future. But I also believe that we can acknowledge that and, with an eye towards accessibility (and, more broadly, inclusion), make thoughtful, considerate, and intentional changes in our approaches to AI that will reduce harm over time as well. Today, tomorrow, and well into the future.

Many thanks to Kartik Sawhney for helping me with the development of this piece, Ashley Bischoff for her invaluable editorial assistance, and, of course, Joe Dolson for the prompt.

The Wax and the Wane of the Web

I offer a single bit of advice to friends and family when they become new parents: When you start to think that you’ve got everything figured out, everything will change. Just as you start to get the hang of feedings, diapers, and regular naps, it’s time for solid food, potty training, and overnight sleeping. When you figure those out, it’s time for preschool and rare naps. The cycle goes on and on.

The same applies for those of us working in design and development these days. Having worked on the web for almost three decades at this point, I’ve seen the regular wax and wane of ideas, techniques, and technologies. Each time that we as developers and designers get into a regular rhythm, some new idea or technology comes along to shake things up and remake our world.

How we got here

I built my first website in the mid-’90s. Design and development on the web back then was a free-for-all, with few established norms. For any layout aside from a single column, we used table elements, often with empty cells containing a single pixel spacer GIF to add empty space. We styled text with numerous font tags, nesting the tags every time we wanted to vary the font style. And we had only three or four typefaces to choose from: Arial, Courier, or Times New Roman. When Verdana and Georgia came out in 1996, we rejoiced because our options had nearly doubled. The only safe colors to choose from were the 216 “web safe” colors known to work across platforms. The few interactive elements (like contact forms, guest books, and counters) were mostly powered by CGI scripts (predominantly written in Perl at the time). Achieving any kind of unique look involved a pile of hacks all the way down. Interaction was often limited to specific pages in a site.

The birth of web standards

At the turn of the century, a new cycle started. Crufty code littered with table layouts and font tags waned, and a push for web standards waxed. Newer technologies like CSS got more widespread adoption by browsers makers, developers, and designers. This shift toward standards didn’t happen accidentally or overnight. It took active engagement between the W3C and browser vendors and heavy evangelism from folks like the Web Standards Project to build standards. A List Apart and books like Designing with Web Standards by Jeffrey Zeldman played key roles in teaching developers and designers why standards are important, how to implement them, and how to sell them to their organizations. And approaches like progressive enhancement introduced the idea that content should be available for all browsers—with additional enhancements available for more advanced browsers. Meanwhile, sites like the CSS Zen Garden showcased just how powerful and versatile CSS can be when combined with a solid semantic HTML structure.

Server-side languages like PHP, Java, and .NET overtook Perl as the predominant back-end processors, and the cgi-bin was tossed in the trash bin. With these better server-side tools came the first era of web applications, starting with content-management systems (particularly in the blogging space with tools like Blogger, Grey Matter, Movable Type, and WordPress). In the mid-2000s, AJAX opened doors for asynchronous interaction between the front end and back end. Suddenly, pages could update their content without needing to reload. A crop of JavaScript frameworks like Prototype, YUI, and jQuery arose to help developers build more reliable client-side interaction across browsers that had wildly varying levels of standards support. Techniques like image replacement let crafty designers and developers display fonts of their choosing. And technologies like Flash made it possible to add animations, games, and even more interactivity.

These new technologies, standards, and techniques reinvigorated the industry in many ways. Web design flourished as designers and developers explored more diverse styles and layouts. But we still relied on tons of hacks. Early CSS was a huge improvement over table-based layouts when it came to basic layout and text styling, but its limitations at the time meant that designers and developers still relied heavily on images for complex shapes (such as rounded or angled corners) and tiled backgrounds for the appearance of full-length columns (among other hacks). Complicated layouts required all manner of nested floats or absolute positioning (or both). Flash and image replacement for custom fonts was a great start toward varying the typefaces from the big five, but both hacks introduced accessibility and performance problems. And JavaScript libraries made it easy for anyone to add a dash of interaction to pages, although at the cost of doubling or even quadrupling the download size of simple websites.

The web as software platform

The symbiosis between the front end and back end continued to improve, and that led to the current era of modern web applications. Between expanded server-side programming languages (which kept growing to include Ruby, Python, Go, and others) and newer front-end tools like React, Vue, and Angular, we could build fully capable software on the web. Alongside these tools came others, including collaborative version control, build automation, and shared package libraries. What was once primarily an environment for linked documents became a realm of infinite possibilities.

At the same time, mobile devices became more capable, and they gave us internet access in our pockets. Mobile apps and responsive design opened up opportunities for new interactions anywhere and any time.

This combination of capable mobile devices and powerful development tools contributed to the waxing of social media and other centralized tools for people to connect and consume. As it became easier and more common to connect with others directly on Twitter, Facebook, and even Slack, the desire for hosted personal sites waned. Social media offered connections on a global scale, with both the good and bad that that entails.

Want a much more extensive history of how we got here, with some other takes on ways that we can improve? Jeremy Keith wrote “Of Time and the Web.” Or check out the “Web Design History Timeline” at the Web Design Museum. Neal Agarwal also has a fun tour through “Internet Artifacts.”

Where we are now

In the last couple of years, it’s felt like we’ve begun to reach another major inflection point. As social-media platforms fracture and wane, there’s been a growing interest in owning our own content again. There are many different ways to make a website, from the tried-and-true classic of hosting plain HTML files to static site generators to content management systems of all flavors. The fracturing of social media also comes with a cost: we lose crucial infrastructure for discovery and connection. Webmentions, RSS, ActivityPub, and other tools of the IndieWeb can help with this, but they’re still relatively underimplemented and hard to use for the less nerdy. We can build amazing personal websites and add to them regularly, but without discovery and connection, it can sometimes feel like we may as well be shouting into the void.

Browser support for CSS, JavaScript, and other standards like web components has accelerated, especially through efforts like Interop. New technologies gain support across the board in a fraction of the time that they used to. I often learn about a new feature and check its browser support only to find that its coverage is already above 80 percent. Nowadays, the barrier to using newer techniques often isn’t browser support but simply the limits of how quickly designers and developers can learn what’s available and how to adopt it.

Today, with a few commands and a couple of lines of code, we can prototype almost any idea. All the tools that we now have available make it easier than ever to start something new. But the upfront cost that these frameworks may save in initial delivery eventually comes due as upgrading and maintaining them becomes a part of our technical debt.

If we rely on third-party frameworks, adopting new standards can sometimes take longer since we may have to wait for those frameworks to adopt those standards. These frameworks—which used to let us adopt new techniques sooner—have now become hindrances instead. These same frameworks often come with performance costs too, forcing users to wait for scripts to load before they can read or interact with pages. And when scripts fail (whether through poor code, network issues, or other environmental factors), there’s often no alternative, leaving users with blank or broken pages.

Where do we go from here?

Today’s hacks help to shape tomorrow’s standards. And there’s nothing inherently wrong with embracing hacks—for now—to move the present forward. Problems only arise when we’re unwilling to admit that they’re hacks or we hesitate to replace them. So what can we do to create the future we want for the web?

Build for the long haul. Optimize for performance, for accessibility, and for the user. Weigh the costs of those developer-friendly tools. They may make your job a little easier today, but how do they affect everything else? What’s the cost to users? To future developers? To standards adoption? Sometimes the convenience may be worth it. Sometimes it’s just a hack that you’ve grown accustomed to. And sometimes it’s holding you back from even better options.

Start from standards. Standards continue to evolve over time, but browsers have done a remarkably good job of continuing to support older standards. The same isn’t always true of third-party frameworks. Sites built with even the hackiest of HTML from the ’90s still work just fine today. The same can’t always be said of sites built with frameworks even after just a couple years.

Design with care. Whether your craft is code, pixels, or processes, consider the impacts of each decision. The convenience of many a modern tool comes at the cost of not always understanding the underlying decisions that have led to its design and not always considering the impact that those decisions can have. Rather than rushing headlong to “move fast and break things,” use the time saved by modern tools to consider more carefully and design with deliberation.

Always be learning. If you’re always learning, you’re also growing. Sometimes it may be hard to pinpoint what’s worth learning and what’s just today’s hack. You might end up focusing on something that won’t matter next year, even if you were to focus solely on learning standards. (Remember XHTML?) But constant learning opens up new connections in your brain, and the hacks that you learn one day may help to inform different experiments another day.

Play, experiment, and be weird! This web that we’ve built is the ultimate experiment. It’s the single largest human endeavor in history, and yet each of us can create our own pocket within it. Be courageous and try new things. Build a playground for ideas. Make goofy experiments in your own mad science lab. Start your own small business. There has never been a more empowering place to be creative, take risks, and explore what we’re capable of.

Share and amplify. As you experiment, play, and learn, share what’s worked for you. Write on your own website, post on whichever social media site you prefer, or shout it from a TikTok. Write something for A List Apart! But take the time to amplify others too: find new voices, learn from them, and share what they’ve taught you.

Go forth and make

As designers and developers for the web (and beyond), we’re responsible for building the future every day, whether that may take the shape of personal websites, social media tools used by billions, or anything in between. Let’s imbue our values into the things that we create, and let’s make the web a better place for everyone. Create that thing that only you are uniquely qualified to make. Then share it, make it better, make it again, or make something new. Learn. Make. Share. Grow. Rinse and repeat. Every time you think that you’ve mastered the web, everything will change.

To Ignite a Personalization Practice, Run this Prepersonalization Workshop

Picture this. You’ve joined a squad at your company that’s designing new product features with an emphasis on automation or AI. Or your company has just implemented a personalization engine. Either way, you’re designing with data. Now what? When it comes to designing for personalization, there are many cautionary tales, no overnight successes, and few guides for the perplexed.

Between the fantasy of getting it right and the fear of it going wrong—like when we encounter “persofails” in the vein of a company repeatedly imploring everyday consumers to buy additional toilet seats—the personalization gap is real. It’s an especially confounding place to be a digital professional without a map, a compass, or a plan.

For those of you venturing into personalization, there’s no Lonely Planet and few tour guides because effective personalization is so specific to each organization’s talent, technology, and market position.

But you can ensure that your team has packed its bags sensibly.

There’s a DIY formula to increase your chances for success. At minimum, you’ll defuse your boss’s irrational exuberance. Before the party you’ll need to effectively prepare.

We call it prepersonalization.

Behind the music

Consider Spotify’s DJ feature, which debuted this past year.

We’re used to seeing the polished final result of a personalization feature. Before the year-end award, the making-of backstory, or the behind-the-scenes victory lap, a personalized feature had to be conceived, budgeted, and prioritized. Before any personalization feature goes live in your product or service, it lives amid a backlog of worthy ideas for expressing customer experiences more dynamically.

So how do you know where to place your personalization bets? How do you design consistent interactions that won’t trip up users or—worse—breed mistrust? We’ve found that for many budgeted programs to justify their ongoing investments, they first needed one or more workshops to convene key stakeholders and internal customers of the technology. Make yours count.

From Big Tech to fledgling startups, we’ve seen the same evolution up close with our clients. In our experiences with working on small and large personalization efforts, a program’s ultimate track record—and its ability to weather tough questions, work steadily toward shared answers, and organize its design and technology efforts—turns on how effectively these prepersonalization activities play out.

Time and again, we’ve seen effective workshops separate future success stories from unsuccessful efforts, saving countless time, resources, and collective well-being in the process.

A personalization practice involves a multiyear effort of testing and feature development. It’s not a switch-flip moment in your tech stack. It’s best managed as a backlog that often evolves through three steps:

- customer experience optimization (CXO, also known as A/B testing or experimentation)

- always-on automations (whether rules-based or machine-generated)

- mature features or standalone product development (such as Spotify’s DJ experience)

This is why we created our progressive personalization framework and why we’re field-testing an accompanying deck of cards: we believe that there’s a base grammar, a set of “nouns and verbs” that your organization can use to design experiences that are customized, personalized, or automated. You won’t need these cards. But we strongly recommend that you create something similar, whether that might be digital or physical.

Set your kitchen timer

How long does it take to cook up a prepersonalization workshop? The surrounding assessment activities that we recommend including can (and often do) span weeks. For the core workshop, we recommend aiming for two to three days. Here’s a summary of our broader approach along with details on the essential first-day activities.

The full arc of the wider workshop is threefold:

- Kickstart: This sets the terms of engagement as you focus on the opportunity as well as the readiness and drive of your team and your leadership. .

- Plan your work: This is the heart of the card-based workshop activities where you specify a plan of attack and the scope of work.

- Work your plan: This phase is all about creating a competitive environment for team participants to individually pitch their own pilots that each contain a proof-of-concept project, its business case, and its operating model.

Give yourself at least a day, split into two large time blocks, to power through a concentrated version of those first two phases.

Kickstart: Whet your appetite

We call the first lesson the “landscape of connected experience.” It explores the personalization possibilities in your organization. A connected experience, in our parlance, is any UX requiring the orchestration of multiple systems of record on the backend. This could be a content-management system combined with a marketing-automation platform. It could be a digital-asset manager combined with a customer-data platform.

Spark conversation by naming consumer examples and business-to-business examples of connected experience interactions that you admire, find familiar, or even dislike. This should cover a representative range of personalization patterns, including automated app-based interactions (such as onboarding sequences or wizards), notifications, and recommenders. We have a catalog of these in the cards. Here’s a list of 142 different interactions to jog your thinking.

This is all about setting the table. What are the possible paths for the practice in your organization? If you want a broader view, here’s a long-form primer and a strategic framework.

Assess each example that you discuss for its complexity and the level of effort that you estimate that it would take for your team to deliver that feature (or something similar). In our cards, we divide connected experiences into five levels: functions, features, experiences, complete products, and portfolios. Size your own build here. This will help to focus the conversation on the merits of ongoing investment as well as the gap between what you deliver today and what you want to deliver in the future.

Next, have your team plot each idea on the following 2×2 grid, which lays out the four enduring arguments for a personalized experience. This is critical because it emphasizes how personalization can not only help your external customers but also affect your own ways of working. It’s also a reminder (which is why we used the word argument earlier) of the broader effort beyond these tactical interventions.

Each team member should vote on where they see your product or service putting its emphasis. Naturally, you can’t prioritize all of them. The intention here is to flesh out how different departments may view their own upsides to the effort, which can vary from one to the next. Documenting your desired outcomes lets you know how the team internally aligns across representatives from different departments or functional areas.

The third and final kickstart activity is about naming your personalization gap. Is your customer journey well documented? Will data and privacy compliance be too big of a challenge? Do you have content metadata needs that you have to address? (We’re pretty sure that you do: it’s just a matter of recognizing the relative size of that need and its remedy.) In our cards, we’ve noted a number of program risks, including common team dispositions. Our Detractor card, for example, lists six stakeholder behaviors that hinder progress.

Effectively collaborating and managing expectations is critical to your success. Consider the potential barriers to your future progress. Press the participants to name specific steps to overcome or mitigate those barriers in your organization. As studies have shown, personalization efforts face many common barriers.

At this point, you’ve hopefully discussed sample interactions, emphasized a key area of benefit, and flagged key gaps? Good—you’re ready to continue.

Hit that test kitchen

Next, let’s look at what you’ll need to bring your personalization recipes to life. Personalization engines, which are robust software suites for automating and expressing dynamic content, can intimidate new customers. Their capabilities are sweeping and powerful, and they present broad options for how your organization can conduct its activities. This presents the question: Where do you begin when you’re configuring a connected experience?

What’s important here is to avoid treating the installed software like it were a dream kitchen from some fantasy remodeling project (as one of our client executives memorably put it). These software engines are more like test kitchens where your team can begin devising, tasting, and refining the snacks and meals that will become a part of your personalization program’s regularly evolving menu.

The ultimate menu of the prioritized backlog will come together over the course of the workshop. And creating “dishes” is the way that you’ll have individual team stakeholders construct personalized interactions that serve their needs or the needs of others.

The dishes will come from recipes, and those recipes have set ingredients.

Verify your ingredients

Like a good product manager, you’ll make sure—andyou’ll validate with the right stakeholders present—that you have all the ingredients on hand to cook up your desired interaction (or that you can work out what needs to be added to your pantry). These ingredients include the audience that you’re targeting, content and design elements, the context for the interaction, and your measure for how it’ll come together.

This isn’t just about discovering requirements. Documenting your personalizations as a series of if-then statements lets the team:

- compare findings toward a unified approach for developing features, not unlike when artists paint with the same palette;

- specify a consistent set of interactions that users find uniform or familiar;

- and develop parity across performance measurements and key performance indicators too.

This helps you streamline your designs and your technical efforts while you deliver a shared palette of core motifs of your personalized or automated experience.

Compose your recipe

What ingredients are important to you? Think of a who-what-when-why construct:

- Who are your key audience segments or groups?

- What kind of content will you give them, in what design elements, and under what circumstances?

- And for which business and user benefits?

We first developed these cards and card categories five years ago. We regularly play-test their fit with conference audiences and clients. And we still encounter new possibilities. But they all follow an underlying who-what-when-why logic.

Here are three examples for a subscription-based reading app, which you can generally follow along with right to left in the cards in the accompanying photo below.

- Nurture personalization: When a guest or an unknown visitor interacts with a product title, a banner or alert bar appears that makes it easier for them to encounter a related title they may want to read, saving them time.

- Welcome automation: When there’s a newly registered user, an email is generated to call out the breadth of the content catalog and to make them a happier subscriber.

- Winback automation: Before their subscription lapses or after a recent failed renewal, a user is sent an email that gives them a promotional offer to suggest that they reconsider renewing or to remind them to renew.

A useful preworkshop activity may be to think through a first draft of what these cards might be for your organization, although we’ve also found that this process sometimes flows best through cocreating the recipes themselves. Start with a set of blank cards, and begin labeling and grouping them through the design process, eventually distilling them to a refined subset of highly useful candidate cards.

You can think of the later stages of the workshop as moving from recipes toward a cookbook in focus—like a more nuanced customer-journey mapping. Individual “cooks” will pitch their recipes to the team, using a common jobs-to-be-done format so that measurability and results are baked in, and from there, the resulting collection will be prioritized for finished design and delivery to production.

Better kitchens require better architecture

Simplifying a customer experience is a complicated effort for those who are inside delivering it. Beware anyone who says otherwise. With that being said, “Complicated problems can be hard to solve, but they are addressable with rules and recipes.”

When personalization becomes a laugh line, it’s because a team is overfitting: they aren’t designing with their best data. Like a sparse pantry, every organization has metadata debt to go along with its technical debt, and this creates a drag on personalization effectiveness. Your AI’s output quality, for example, is indeed limited by your IA. Spotify’s poster-child prowess today was unfathomable before they acquired a seemingly modest metadata startup that now powers its underlying information architecture.

You can definitely stand the heat…

Personalization technology opens a doorway into a confounding ocean of possible designs. Only a disciplined and highly collaborative approach will bring about the necessary focus and intention to succeed. So banish the dream kitchen. Instead, hit the test kitchen to save time, preserve job satisfaction and security, and safely dispense with the fanciful ideas that originate upstairs of the doers in your organization. There are meals to serve and mouths to feed.

This workshop framework gives you a fighting shot at lasting success as well as sound beginnings. Wiring up your information layer isn’t an overnight affair. But if you use the same cookbook and shared recipes, you’ll have solid footing for success. We designed these activities to make your organization’s needs concrete and clear, long before the hazards pile up.

While there are associated costs toward investing in this kind of technology and product design, your ability to size up and confront your unique situation and your digital capabilities is time well spent. Don’t squander it. The proof, as they say, is in the pudding.

User Research Is Storytelling

Ever since I was a boy, I’ve been fascinated with movies. I loved the characters and the excitement—but most of all the stories. I wanted to be an actor. And I believed that I’d get to do the things that Indiana Jones did and go on exciting adventures. I even dreamed up ideas for movies that my friends and I could make and star in. But they never went any further. I did, however, end up working in user experience (UX). Now, I realize that there’s an element of theater to UX—I hadn’t really considered it before, but user research is storytelling. And to get the most out of user research, you need to tell a good story where you bring stakeholders—the product team and decision makers—along and get them interested in learning more.

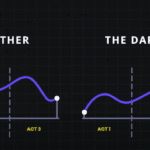

Think of your favorite movie. More than likely it follows a three-act structure that’s commonly seen in storytelling: the setup, the conflict, and the resolution. The first act shows what exists today, and it helps you get to know the characters and the challenges and problems that they face. Act two introduces the conflict, where the action is. Here, problems grow or get worse. And the third and final act is the resolution. This is where the issues are resolved and the characters learn and change. I believe that this structure is also a great way to think about user research, and I think that it can be especially helpful in explaining user research to others.

Use storytelling as a structure to do research

It’s sad to say, but many have come to see research as being expendable. If budgets or timelines are tight, research tends to be one of the first things to go. Instead of investing in research, some product managers rely on designers or—worse—their own opinion to make the “right” choices for users based on their experience or accepted best practices. That may get teams some of the way, but that approach can so easily miss out on solving users’ real problems. To remain user-centered, this is something we should avoid. User research elevates design. It keeps it on track, pointing to problems and opportunities. Being aware of the issues with your product and reacting to them can help you stay ahead of your competitors.

In the three-act structure, each act corresponds to a part of the process, and each part is critical to telling the whole story. Let’s look at the different acts and how they align with user research.

Act one: setup

The setup is all about understanding the background, and that’s where foundational research comes in. Foundational research (also called generative, discovery, or initial research) helps you understand users and identify their problems. You’re learning about what exists today, the challenges users have, and how the challenges affect them—just like in the movies. To do foundational research, you can conduct contextual inquiries or diary studies (or both!), which can help you start to identify problems as well as opportunities. It doesn’t need to be a huge investment in time or money.

Erika Hall writes about minimum viable ethnography, which can be as simple as spending 15 minutes with a user and asking them one thing: “‘Walk me through your day yesterday.’ That’s it. Present that one request. Shut up and listen to them for 15 minutes. Do your damndest to keep yourself and your interests out of it. Bam, you’re doing ethnography.” According to Hall, “[This] will probably prove quite illuminating. In the highly unlikely case that you didn’t learn anything new or useful, carry on with enhanced confidence in your direction.”

This makes total sense to me. And I love that this makes user research so accessible. You don’t need to prepare a lot of documentation; you can just recruit participants and do it! This can yield a wealth of information about your users, and it’ll help you better understand them and what’s going on in their lives. That’s really what act one is all about: understanding where users are coming from.

Jared Spool talks about the importance of foundational research and how it should form the bulk of your research. If you can draw from any additional user data that you can get your hands on, such as surveys or analytics, that can supplement what you’ve heard in the foundational studies or even point to areas that need further investigation. Together, all this data paints a clearer picture of the state of things and all its shortcomings. And that’s the beginning of a compelling story. It’s the point in the plot where you realize that the main characters—or the users in this case—are facing challenges that they need to overcome. Like in the movies, this is where you start to build empathy for the characters and root for them to succeed. And hopefully stakeholders are now doing the same. Their sympathy may be with their business, which could be losing money because users can’t complete certain tasks. Or maybe they do empathize with users’ struggles. Either way, act one is your initial hook to get the stakeholders interested and invested.

Once stakeholders begin to understand the value of foundational research, that can open doors to more opportunities that involve users in the decision-making process. And that can guide product teams toward being more user-centered. This benefits everyone—users, the product, and stakeholders. It’s like winning an Oscar in movie terms—it often leads to your product being well received and successful. And this can be an incentive for stakeholders to repeat this process with other products. Storytelling is the key to this process, and knowing how to tell a good story is the only way to get stakeholders to really care about doing more research.

This brings us to act two, where you iteratively evaluate a design or concept to see whether it addresses the issues.

Act two: conflict

Act two is all about digging deeper into the problems that you identified in act one. This usually involves directional research, such as usability tests, where you assess a potential solution (such as a design) to see whether it addresses the issues that you found. The issues could include unmet needs or problems with a flow or process that’s tripping users up. Like act two in a movie, more issues will crop up along the way. It’s here that you learn more about the characters as they grow and develop through this act.

Usability tests should typically include around five participants according to Jakob Nielsen, who found that that number of users can usually identify most of the problems: “As you add more and more users, you learn less and less because you will keep seeing the same things again and again… After the fifth user, you are wasting your time by observing the same findings repeatedly but not learning much new.”

There are parallels with storytelling here too; if you try to tell a story with too many characters, the plot may get lost. Having fewer participants means that each user’s struggles will be more memorable and easier to relay to other stakeholders when talking about the research. This can help convey the issues that need to be addressed while also highlighting the value of doing the research in the first place.

Researchers have run usability tests in person for decades, but you can also conduct usability tests remotely using tools like Microsoft Teams, Zoom, or other teleconferencing software. This approach has become increasingly popular since the beginning of the pandemic, and it works well. You can think of in-person usability tests like going to a play and remote sessions as more like watching a movie. There are advantages and disadvantages to each. In-person usability research is a much richer experience. Stakeholders can experience the sessions with other stakeholders. You also get real-time reactions—including surprise, agreement, disagreement, and discussions about what they’re seeing. Much like going to a play, where audiences get to take in the stage, the costumes, the lighting, and the actors’ interactions, in-person research lets you see users up close, including their body language, how they interact with the moderator, and how the scene is set up.

If in-person usability testing is like watching a play—staged and controlled—then conducting usability testing in the field is like immersive theater where any two sessions might be very different from one another. You can take usability testing into the field by creating a replica of the space where users interact with the product and then conduct your research there. Or you can go out to meet users at their location to do your research. With either option, you get to see how things work in context, things come up that wouldn’t have in a lab environment—and conversion can shift in entirely different directions. As researchers, you have less control over how these sessions go, but this can sometimes help you understand users even better. Meeting users where they are can provide clues to the external forces that could be affecting how they use your product. In-person usability tests provide another level of detail that’s often missing from remote usability tests.

That’s not to say that the “movies”—remote sessions—aren’t a good option. Remote sessions can reach a wider audience. They allow a lot more stakeholders to be involved in the research and to see what’s going on. And they open the doors to a much wider geographical pool of users. But with any remote session there is the potential of time wasted if participants can’t log in or get their microphone working.

The benefit of usability testing, whether remote or in person, is that you get to see real users interact with the designs in real time, and you can ask them questions to understand their thought processes and grasp of the solution. This can help you not only identify problems but also glean why they’re problems in the first place. Furthermore, you can test hypotheses and gauge whether your thinking is correct. By the end of the sessions, you’ll have a much clearer picture of how usable the designs are and whether they work for their intended purposes. Act two is the heart of the story—where the excitement is—but there can be surprises too. This is equally true of usability tests. Often, participants will say unexpected things, which change the way that you look at things—and these twists in the story can move things in new directions.

Unfortunately, user research is sometimes seen as expendable. And too often usability testing is the only research process that some stakeholders think that they ever need. In fact, if the designs that you’re evaluating in the usability test aren’t grounded in a solid understanding of your users (foundational research), there’s not much to be gained by doing usability testing in the first place. That’s because you’re narrowing the focus of what you’re getting feedback on, without understanding the users’ needs. As a result, there’s no way of knowing whether the designs might solve a problem that users have. It’s only feedback on a particular design in the context of a usability test.

On the other hand, if you only do foundational research, while you might have set out to solve the right problem, you won’t know whether the thing that you’re building will actually solve that. This illustrates the importance of doing both foundational and directional research.

In act two, stakeholders will—hopefully—get to watch the story unfold in the user sessions, which creates the conflict and tension in the current design by surfacing their highs and lows. And in turn, this can help motivate stakeholders to address the issues that come up.

Act three: resolution

While the first two acts are about understanding the background and the tensions that can propel stakeholders into action, the third part is about resolving the problems from the first two acts. While it’s important to have an audience for the first two acts, it’s crucial that they stick around for the final act. That means the whole product team, including developers, UX practitioners, business analysts, delivery managers, product managers, and any other stakeholders that have a say in the next steps. It allows the whole team to hear users’ feedback together, ask questions, and discuss what’s possible within the project’s constraints. And it lets the UX research and design teams clarify, suggest alternatives, or give more context behind their decisions. So you can get everyone on the same page and get agreement on the way forward.

This act is mostly told in voiceover with some audience participation. The researcher is the narrator, who paints a picture of the issues and what the future of the product could look like given the things that the team has learned. They give the stakeholders their recommendations and their guidance on creating this vision.

Nancy Duarte in the Harvard Business Review offers an approach to structuring presentations that follow a persuasive story. “The most effective presenters use the same techniques as great storytellers: By reminding people of the status quo and then revealing the path to a better way, they set up a conflict that needs to be resolved,” writes Duarte. “That tension helps them persuade the audience to adopt a new mindset or behave differently.”

This type of structure aligns well with research results, and particularly results from usability tests. It provides evidence for “what is”—the problems that you’ve identified. And “what could be”—your recommendations on how to address them. And so on and so forth.

You can reinforce your recommendations with examples of things that competitors are doing that could address these issues or with examples where competitors are gaining an edge. Or they can be visual, like quick mockups of how a new design could look that solves a problem. These can help generate conversation and momentum. And this continues until the end of the session when you’ve wrapped everything up in the conclusion by summarizing the main issues and suggesting a way forward. This is the part where you reiterate the main themes or problems and what they mean for the product—the denouement of the story. This stage gives stakeholders the next steps and hopefully the momentum to take those steps!

While we are nearly at the end of this story, let’s reflect on the idea that user research is storytelling. All the elements of a good story are there in the three-act structure of user research:

- Act one: You meet the protagonists (the users) and the antagonists (the problems affecting users). This is the beginning of the plot. In act one, researchers might use methods including contextual inquiry, ethnography, diary studies, surveys, and analytics. The output of these methods can include personas, empathy maps, user journeys, and analytics dashboards.

- Act two: Next, there’s character development. There’s conflict and tension as the protagonists encounter problems and challenges, which they must overcome. In act two, researchers might use methods including usability testing, competitive benchmarking, and heuristics evaluation. The output of these can include usability findings reports, UX strategy documents, usability guidelines, and best practices.

- Act three: The protagonists triumph and you see what a better future looks like. In act three, researchers may use methods including presentation decks, storytelling, and digital media. The output of these can be: presentation decks, video clips, audio clips, and pictures.

The researcher has multiple roles: they’re the storyteller, the director, and the producer. The participants have a small role, but they are significant characters (in the research). And the stakeholders are the audience. But the most important thing is to get the story right and to use storytelling to tell users’ stories through research. By the end, the stakeholders should walk away with a purpose and an eagerness to resolve the product’s ills.

So the next time that you’re planning research with clients or you’re speaking to stakeholders about research that you’ve done, think about how you can weave in some storytelling. Ultimately, user research is a win-win for everyone, and you just need to get stakeholders interested in how the story ends.

From Beta to Bedrock: Build Products that Stick.

As a product builder over too many years to mention, I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve seen promising ideas go from zero to hero in a few weeks, only to fizzle out within months.

Financial products, which is the field I work in, are no exception. With people’s real hard-earned money on the line, user expectations running high, and a crowded market, it’s tempting to throw as many features at the wall as possible and hope something sticks. But this approach is a recipe for disaster. Here’s why:

The pitfalls of feature-first development

When you start building a financial product from the ground up, or are migrating existing customer journeys from paper or telephony channels onto online banking or mobile apps, it’s easy to get caught up in the excitement of creating new features. You might think, “If I can just add one more thing that solves this particular user problem, they’ll love me!” But what happens when you inevitably hit a roadblock because the narcs (your security team!) don’t like it? When a hard-fought feature isn’t as popular as you thought, or it breaks due to unforeseen complexity?

This is where the concept of Minimum Viable Product (MVP) comes in. Jason Fried’s book Getting Real and his podcast Rework often touch on this idea, even if he doesn’t always call it that. An MVP is a product that provides just enough value to your users to keep them engaged, but not so much that it becomes overwhelming or difficult to maintain. It sounds like an easy concept but it requires a razor sharp eye, a ruthless edge and having the courage to stick by your opinion because it is easy to be seduced by “the Columbo Effect”… when there’s always “just one more thing…” that someone wants to add.

The problem with most finance apps, however, is that they often become a reflection of the internal politics of the business rather than an experience solely designed around the customer. This means that the focus is on delivering as many features and functionalities as possible to satisfy the needs and desires of competing internal departments, rather than providing a clear value proposition that is focused on what the people out there in the real world want. As a result, these products can very easily bloat to become a mixed bag of confusing, unrelated and ultimately unlovable customer experiences—a feature salad, you might say.

The importance of bedrock

So what’s a better approach? How can we build products that are stable, user-friendly, and—most importantly—stick?

That’s where the concept of “bedrock” comes in. Bedrock is the core element of your product that truly matters to users. It’s the fundamental building block that provides value and stays relevant over time.

In the world of retail banking, which is where I work, the bedrock has got to be in and around the regular servicing journeys. People open their current account once in a blue moon but they look at it every day. They sign up for a credit card every year or two, but they check their balance and pay their bill at least once a month.

Identifying the core tasks that people want to do and then relentlessly striving to make them easy to do, dependable, and trustworthy is where the gravy’s at.

But how do you get to bedrock? By focusing on the “MVP” approach, prioritizing simplicity, and iterating towards a clear value proposition. This means cutting out unnecessary features and focusing on delivering real value to your users.

It also means having some guts, because your colleagues might not always instantly share your vision to start with. And controversially, sometimes it can even mean making it clear to customers that you’re not going to come to their house and make their dinner. The occasional “opinionated user interface design” (i.e. clunky workaround for edge cases) might sometimes be what you need to use to test a concept or buy you space to work on something more important.

Practical strategies for building financial products that stick

So what are the key strategies I’ve learned from my own experience and research?

- Start with a clear “why”: What problem are you trying to solve? For whom? Make sure your mission is crystal clear before building anything. Make sure it aligns with your company’s objectives, too.

- Focus on a single, core feature and obsess on getting that right before moving on to something else: Resist the temptation to add too many features at once. Instead, choose one that delivers real value and iterate from there.

- Prioritize simplicity over complexity: Less is often more when it comes to financial products. Cut out unnecessary bells and whistles and keep the focus on what matters most.

- Embrace continuous iteration: Bedrock isn’t a fixed destination—it’s a dynamic process. Continuously gather user feedback, refine your product, and iterate towards that bedrock state.

- Stop, look and listen: Don’t just test your product as part of your delivery process—test it repeatedly in the field. Use it yourself. Run A/B tests. Gather user feedback. Talk to people who use it, and refine accordingly.

The bedrock paradox

There’s an interesting paradox at play here: building towards bedrock means sacrificing some short-term growth potential in favour of long-term stability. But the payoff is worth it—products built with a focus on bedrock will outlast and outperform their competitors, and deliver sustained value to users over time.

So, how do you start your journey towards bedrock? Take it one step at a time. Start by identifying those core elements that truly matter to your users. Focus on building and refining a single, powerful feature that delivers real value. And above all, test obsessively—for, in the words of Abraham Lincoln, Alan Kay, or Peter Drucker (whomever you believe!!), “The best way to predict the future is to create it.”

George Clooney (and Everyone Else) Needs to Stop Apologizing for ‘Campy Batman’

When Batman Begins came out 20 years ago, almost to the day, I was a high school nerd. Which is to say that I was (of course) obsessed that someone had finally taken Batman seriously. And to be honest, I remain a great booster for what Christopher Nolan and Christian Bale achieved across all three […]

The post George Clooney (and Everyone Else) Needs to Stop Apologizing for ‘Campy Batman’ appeared first on Den of Geek.

As the world’s foremost wallcrawler, Spider-Man has been known to hang off of things for a while. But 27 years is pushing it, even for him. Yet that’s how long Spidey’s been waiting for a resolution to the cliffhanger that closed out Spider-Man: The Animated Series, the popular cartoon show that ran from 1994 to 1998 on the Fox Network.

The series ended in ’98 with Spider-Man following Madame Web’s instructions to find his wife Mary Jane, who had been lost in the multiverse after being replaced by a clone in his own timeline. We never see the two of them actually reunited, an error that Marvel Comics will finally rectify with the release of the upcoming four-issue miniseries Spider-Man ’94, from legendary writer J.M. DeMatteis (Kraven’s Last Hunt) and artist Jim Towe.

Spider-Man ’94 is just the latest cartoon series of the era to get a nod in recent years. Recently Nicholas Hoult credited Clancy Brown‘s performance in Superman: The Animated Series as an inspiration for his take on Lex Luthor, and a new Captain Planet and the Planeteers comic book released this year from Dynamite Entertainment. There is also the sensation that is Disney+’s X-Men ’97 (which we should note also only got a greenlight after Marvel Comics dipped its toe into nostalgia via the X-Men ’92 miniseries in 2015). In other words, it’s becoming kind of obvious that the ’90s nailed superheroes.

So as we wait for Spider-Man ’94 to finally get Spidey off that cliff, let’s look at some of the best cartoon series of the era and what they did so well.

Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles (1987-1996)

Yes, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles debuted in the late ’80s, but the series hit its peak in 1990 and set the stage for the superhero boom to come. After all, the Turtles made their debut not in cartoons, but in the pages of comics independently produced by creators Peter Laird and Kevin Eastman—comics that began as a parody of Frank Miller‘s Daredevil.

For those of us who were kids during the Turtles’ initial boom, the original comics were the stuff of legend: black and white and apparently edgy, they were a forbidden fruit that we all wanted to seek out but were afraid of what we’d find. Looking back, however, it’s remarkable to see how much of the goofy Turtles lore comes directly from those first comics, including the alien Utroms (represented in the cartoon by Krang) and the psycho vigilante Casey Jones.

Whatever one feels about that revelation, the fact that the Ninja Turtles got fans to seek out indie comics is still remarkable. That impulse did lead to a glut of cartoon shows based on indie comics, some great (The Tick) and some less so (Wild C.A.T.S.), but it reminded people that superheroes can thrive outside of the Marvel and DC Universes, a lesson still relevant today.

cnx({

playerId: “106e33c0-3911-473c-b599-b1426db57530”,

}).render(“0270c398a82f44f49c23c16122516796”);

});

Batman: The Animated Series (1992–1995)

Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles may have kicked off the animated superhero boom, but the movement was perfected by Batman: The Animated Series. Created by Bruce Timm and Eric Radomski, Batman: TAS moved the genre forward by looking backward. Set in an indistinct time period and only tangentially related to the Tim Burton movies, Batman: TAS worked because of Timm’s barrel-chested designs and superb scripts by writers like Paul Dini. Together they distilled the classic tropes and sagas from previous decades of comics into something that made the hero timeless.

Most episodes of Batman: TAS told standalone tales, not unlike those you would find in an individual issue of Batman or Detective Comics in the Golden Age or the Bronze Age. Some sort of baddie—whether it be a costumed freak like Joker or Scarecrow, or a thug like Rupert Thorne—would threaten Gotham, and Batman would use all the tools at his disposal to stop them.

Simple as that premise was, Batman: TAS also found efficient, and even definitive, ways of uncovering pathos in these archetypes. Mr. Freeze went from a joke to a tragic figure, the Joker never felt so menacing (without veering into gritty ugliness), and Poison Ivy made her first steps toward becoming the antihero we know today—including by, ahem, partnering up with a TAS original creation, Harley Quinn.

Batman: The Animated Series launched a host of spinoffs, including the aforementioned Superman, the future-set sequel Batman Beyond, and Justice League. The legacy continues today, not only in Timm’s spiritual successor Batman: Caped Crusader, but also in every adaptation that tries to tell solid superhero stories for a general audience.

X-Men: The Animated Series (1992-1997)

First, let’s address the elephant in the room. Yes, X-Men ’97 technically resolved the Spider-Man: The Animated Series cliffhanger in the season one finale where we see a glimpse of Mary Jane standing next to Spidey, suggesting that the two did reunite and make their way home.

That out of the way, let’s talk about what X-Men: The Animated Series did really well: it brought the comics to the masses. While Batman: The Animated Series deserves praise for its economic storytelling, that approach had largely been abandoned in its source material. By the early 1990s, superhero comics were often convoluted, soap operatic stories with complicated interpersonal relationships. No one did these types of stories better than Chris Claremont, who started writing the X-Men in 1975, transforming the team from Marvel c-listers into the biggest heroes on the newsstand by 1992.

Instead of trying to reinvent the wheel, X-Men: TAS followed the leader, adapting Claremont’s stories and using the recent visual redesigns of superstar artist Jim Lee. Somehow it worked, bringing bonkers tales like the Mutant Massacre and Fall of the Mutants to the small screen. It hooked a whole new era of fans. Of course the most pronounced successor to X-Men: The Animated Series is the Disney+ series X-Men ’97, which continues the storylines of the original show and heightens the political messaging. But X-Men: TAS also proved to executives that comic-accurate material wasn’t anathema to general audiences, opening the door for our current entertainment landscape, in which Disney produces billion-dollar adaptations of The Infinity Gauntlet and Secret Wars.

Spider-Man: The Animated Series (1994–1998)

Obviously, Spider-Man: The Animated Series owes a major debt to X-Men: The Animated Series. Like his merry mutant cousins, Spider-Man got to recreate his overstuffed comic book adventures on the small screen. However, even more than X-Men, Spider-Man: The Animated Series streamlined the comic book stories in a way that set the stage for future adaptations.

For evidence, take a look at the way the cartoon handled Venom. In the comics, Spider-Man got his black suit while off-planet in Secret Wars. For a while, Peter wore his black suit as his new costume, but eventually returned to his blue and red togs when he grew uncomfortable with having a symbiote. In 1988, four years after the black suit debuted, new character Eddie Brock wore the costume and became Venom.

While the slower pace helps build up the relationship between Spidey and Venom, cartoon viewers can’t wait four years for a fan-favorite baddie to exist. So in the cartoon, the symbiote attaches itself to a meteor brought to earth by astronaut John Jameson, which then jumps to Spidey and eventually Eddie Brock. The whole thing gets told in three episodes, without sacrificing any of the other-worldliness central to Venom. It also introduced the idea of the symbiote corrupting Peter Parker’s persona, and making him turn toward “dark Spider-Man.” These are all elements that have been incorporated to some capacity in every future adaptation of the Venom character, on the small screen and the big.

Examples such as those showed the creators of modern superhero movies and shows that you could get weird with the characters—as long as you were efficient. It was a benchmark for Spider-Man: TAS, the first major adaptation of the comics to capture the soap operatic appeal of the character and his “days of lives” romances as a twentysomething in NYC—a core aspect of the character that arguably no film has balanced quite so well.

Superman: The Animated Series (1996–2000)

On first glance, it would be easy to say Superman: The Animated Series is to Batman what Spider-Man: The Animated Series is to X-Men. That is, a solid cartoon series that doesn’t quite rival the original. However, Superman: TAS also showed something important about creating Superman and Batman stories, something that certain people (coughZackSnyderwithManofSteelcough) forgot: Superman isn’t Batman and his stories need to be handled differently.

Whereas Batman: TAS painted Gotham City in the dark tones of film noir, Superman: TAS draws from the optimism of old World’s Fair celebrations and 1950s sci-fi to make Metropolis feel like its set in some undefined future. There’s certainly a quaintness to the proceedings, what with its cackling businessman Luthor and robo-men like Metallo. But that quaintness never feels outdated.

Moreover, Superman: TAS showed how to tell compelling Superman stories on a regular basis without making the hero feel less super. Yes, this version of Superman was a little more vulnerable than his comic book counterpart, but he always fought for the powerless and did the right thing… which sure sounds a lot like the version of Superman we’re going to see on the big screen this summer.

Justice League Unlimited (2004-2006)

Again, we’re cheating a bit here, since Justice League Unlimited ran in the mid-2000s. But it is an offshoot of three major shows from the 1990s—Batman: The Animated Series, Superman: The Animated Series, and Batman Beyond—and has much more in common with them than it does other 2000s shows, such as Teen Titans or X-Men: Evolution.