Star Trek Crews Ranked from Worst to the Real Number Ones

Star Trek is all about exploring the final frontier. But its also about how you can’t explore it alone. From the naval trappings that inform its starship setting to the utopian United Federation of Planets, Star Trek offers a fundamentally communal vision, a depiction of the future in which humanity has overcome its petty differences […]

The post Star Trek Crews Ranked from Worst to the Real Number Ones appeared first on Den of Geek.

Star Trek is all about exploring the final frontier. But its also about how you can’t explore it alone. From the naval trappings that inform its starship setting to the utopian United Federation of Planets, Star Trek offers a fundamentally communal vision, a depiction of the future in which humanity has overcome its petty differences and work together.

That vision begins on the bridge of each ship in the respective Star Trek series. Yet, as anyone who’s ever visited a Trek-centric website knows well, not all crews are created equal. So here’s our attempt to rank the ten main crews across the Star Trek franchise.

10. Sirena (Picard)

Even if the third and final season of Star Trek: Picard didn’t reunite the TNG crew on a reconstituted Enterprise-D, the crew of the Sirena would be in last place. How could they not be? Owing to Patrick Stewart‘s reluctance to repeat too much of what he previously did as Jean-Luc Picard, the first two seasons of Picard didn’t have a proper crew. Instead, he gathered a rag-tag group to go on an unauthorized mission.

cnx({

playerId: “106e33c0-3911-473c-b599-b1426db57530”,

}).render(“0270c398a82f44f49c23c16122516796”);

});

Some of those members did make for compelling characters. Jeri Ryan has made Seven of Nine only more nuanced over the years, Santiago Cabrera is endlessly watchable as Chris Rios, and Alison Pill manages to find something compelling in the disastrously-written Agnes Jurati. But with duds like Raffi and Elnor on board, Picard shows that rag-tag teams don’t work when audiences don’t enjoy watching the misfits interact. If only the current Trek producers learned that lesson before making Section 31…

9. NX-01 (Enterprise)

Certainly, some will point out that other, more recent shows deserve to be lower than the team on the NX-01, because Enterprise gave each member of its bridge crew at least one character trait. However, this writer contends that it would be better to know nothing about a character than to know that they’re insufferable jerks, which is too often the case aboard the NX-01.

This isn’t to say that Enterprise was completely devoid of interesting figures. Trip Tucker managed to embody the fighter-pilot mentality that the series wanted to harness, T’Pol’s arc showed just how hard it was to build the alliance between Earth and Vulcan, and Phlox is the best doctor on the show. But compared to Archer’s confused belligerence and Reed’s constant whining or creepiness, Mayweather becomes one of the best characters on the show because we can’t hate someone that we know nothing about.

8. Discovery (Discovery)

Discovery belongs toward the bottom because it eschews the ensemble approach that became the franchise’s trademark. Michael Burnham is a solo protagonist in the way Star Trek had not had since TOS (and even then, it was only a one-man show when Shatner got his way). One episode reveals that that Owosekun comes from a planet of space Luddites, another shows that Detmer is mad a Michael for a while about the hunk of mettle in her face, and one of the other guys says he likes to surf… I don’t remember which.

That said, there are some gems in Discovery‘s crew, even in its unusual structure. Sonequa Martin-Green’s considerable charisma isn’t quite enough to make Michael someone worth so much attention, but Mary Wiseman’s earnest and annoying Tilly helped bring out the best in the eventual captain. Doug Jones is incredible as Saru, adding a layered vocal performance to his remarkable-as-usual physical acting. Stamets and Culber sometimes suffered from uneven writing, but they managed to show how a marriage could work on a starship. And Tig Notaro may have just been playing herself in space, but Tig Notaro is great, and she killed every line.

7. Voyager (Voyager)

Voyager very much wanted to return to Next Generation-style storytelling after the more experimental Deep Space Nine. At first, that meant not just a return to episodic storytelling, but also a focus on the ensemble crew. Even better, the series’ premise gave Voyager a great storytelling engine with which to work, as getting stranded in the Delta Quadrant required members of the Maquis, ex-Starfleet officers who rebelled against the organization, to fall in under Janeway’s command.

In an incredibly frustrating move, the producers of Voyager decided to ignore the potential stories in such a conflict. Outside of a handful of episodes here and there, the former Maquis and the Starfleet officers had no issues. Sadly, missed opportunities became the hallmark of the show’s approach to the ensemble, especially once Seven of Nine. From that point on, Harry Kim, B’Elanna Torres, and Tuvok took a back seat to Janeway, Seven, and the Doctor. That trio got plenty of great episodes, and it was always nice when attention turned to some of the other members of crew. But it’s hard to give Voyager special condemnation for its ensemble work.

6. Protostar (Prodigy)

From this point on, all of the Star Trek shows do a good job with their ensembles, and all of the crews are good—the only question is about how good they are. And, for certain, the group of alien children who escape the confines of an alien overlord from the Delta Quadrant and become Starfleet cadets are very good. Prodigy somehow manages to be a kid’s show, a sequel to Discovery, and a darn good Star Trek show, all at once.

That said, the narrative of Prodigy demands that they aren’t quite on the level of the other more professional and seasoned crews on this list. Dal has all the makings of a great captain, Gwyndala will be a great linguist, Jankom Pog will be a great engineer, and so on. But they aren’t there quite yet, because they’re still kids learning about how Starfleet works. That fact makes for fantastic viewing, and we better get at least one more season of Prodigy to see how they develop. But it also puts the crew at the bottom of the good groups on this list.

5. Cerritos (Lower Decks)

At first, it seemed like Lower Decks would be a two-hander with a couple supporting characters, surrounded by thinly-sketched others. Ensigns Mariner and Boimler were the stars, Ensigns Rutherford and Tendi were their friends, and everyone else existed for jokes. But as Lower Decks developed, it became about more than just laughing about horga’hns and Spock Helmets. It became a proper Star Trek show, about exploration and discovery.

As it did so, the characters developed and the crew became more distinct. Mariner and Boimler evolved past just slacker and try-hard, into good Starfleet officers, just like Rutherford and Tendi became more than just players in the leads’ adventures. Even better were the rest of the Cerritos‘s crew, especially Mariner’s mother Carol Freeman. Neither a once-in-a-generation adventurer like Kirk nor a perfect diplomat like Picard, Captain Freeman is just trying to do her job, and she does it well. It’s Freeman’s no-nonsense watch over the Cerritos that allows her crew of goofballs to shine.

4. Enterprise (Strange New Worlds)

The Strange New Worlds crew aboard the pre-Kirk Enterprise is fun to watch. Beginning with Anson Mount’s take on Captain Pike as a cool, supportive older brother, Strange New Worlds feels less like the return to exploration suggested by its title and more of a romp across space starring familiar characters. While the individual episodes may not be to everyone’s tastes, such as the infamous musical episode or the self-parodying proto-holodeck episode, no one can help but smile while watching the cast interact.

Some of that fun comes from the compelling new characters added to the series, the security officer La’an or the cooky engineer Pelia. Likewise, the show has done remarkably well acting as a prequel, giving us belivably younger versions of Uhura, Scotty, and Spock. But the real pleasure of Strange New Worlds has been the way it develops characters we knew only by name. Number One, M’Benga, and Chapel have gone from being footnotes in Trek history to fully-formed characters who deserve mention alongside their more famous counterparts.

3. Enterprise (The Original Series)

I know, I know. The Original Series set the stage! Star Trek wouldn’t be Star Trek without Scotty and Uhura and Sulu and Chekov! While this is true, it’s also true that everyone who wasn’t in the central trio of Kirk, Spock, and McCoy never got much character development, even in films that purported to give them more to do. As director, Leonard Nimoy made a point of spreading the attention to his co-stars in Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home, but that attention still resulted in single bits: Scotty talking into a mouse, Chekov looks for nuclear ‘wessels,’ Sulu checks out a chopper.

However, the fact that the crew is so beloved despite their relatively small amount of screentime makes them all the more impressive. None of the side characters displace the main three, but Nichelle Nichols, James Doohan, Walter Koenig, and George Takei manage to make the most of the attention they get, so that they feel far more fleshed out than they actually are. Thanks to the supporting cast’s work, TOS set the stage for the crews to come.

2. Deep Space Nine (Deep Space Nine)

Deep Space Nine has a bit of an unfair advantage, as its central cast isn’t the crew of a starship; they’re the staff on a space station. That difference allows us to include barkeep Quark and constable Odo, characters that otherwise might not fit on the main crew. But the real secret to DS9‘s success comes down to its commander-turned-captain, Benjamin Sisko. From the very beginning, Sisko was a different type of character than the other leads, a single father who was skeptical of Starfleet and thrust into the position of religious figure.

Because of this distinction, Sisko was able to have different types of interactions with those around him, making for unique interactions with the crew. He saw Dax as both a subordinate and a mentor, thanks to the symbiote she carried. He bonded with O’Brien over feeling like an outsider, while he recognized Garak as a necessary evil. From the top down, DS9 offered new team dynamics, all part of its groundbreaking approach to the franchise.

1. Enterprise (The Next Generation)

The Original Series crew felt like a group of compelling characters who worked and lived together. The Next Generation crew was a a group of compelling characters who worked and lived together. Well, eventually they became that. Part of the problem in the famously uneven first two seasons of TNG is that it tries to replicate the focus on three characters—originally, Picard, Data, and Geordi. But as the series went on (and Stewart gave into playing along with his co-stars), the Enterprise-D became a proper ensemble.

Several episodes demonstrate these dynamics, from the delightful holodeck romps to the gripping two-parters. But none illustrate it better than the series finale, “All Good Things…” Watching Picard check in with the crew across time, only to finally join them in a card game at the end puts the perfect capper on the show. These are explorers and scientists and military personnel, yes. But most of all, these are friends.

The post Star Trek Crews Ranked from Worst to the Real Number Ones appeared first on Den of Geek.

Asynchronous Design Critique: Giving Feedback

Feedback, in whichever form it takes, and whatever it may be called, is one of the most effective soft skills that we have at our disposal to collaboratively get our designs to a better place while growing our own skills and perspectives.

Feedback is also one of the most underestimated tools, and often by assuming that we’re already good at it, we settle, forgetting that it’s a skill that can be trained, grown, and improved. Poor feedback can create confusion in projects, bring down morale, and affect trust and team collaboration over the long term. Quality feedback can be a transformative force.

Practicing our skills is surely a good way to improve, but the learning gets even faster when it’s paired with a good foundation that channels and focuses the practice. What are some foundational aspects of giving good feedback? And how can feedback be adjusted for remote and distributed work environments?

On the web, we can identify a long tradition of asynchronous feedback: from the early days of open source, code was shared and discussed on mailing lists. Today, developers engage on pull requests, designers comment in their favorite design tools, project managers and scrum masters exchange ideas on tickets, and so on.

Design critique is often the name used for a type of feedback that’s provided to make our work better, collaboratively. So it shares a lot of the principles with feedback in general, but it also has some differences.

The content

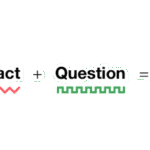

The foundation of every good critique is the feedback’s content, so that’s where we need to start. There are many models that you can use to shape your content. The one that I personally like best—because it’s clear and actionable—is this one from Lara Hogan.

While this equation is generally used to give feedback to people, it also fits really well in a design critique because it ultimately answers some of the core questions that we work on: What? Where? Why? How? Imagine that you’re giving some feedback about some design work that spans multiple screens, like an onboarding flow: there are some pages shown, a flow blueprint, and an outline of the decisions made. You spot something that could be improved. If you keep the three elements of the equation in mind, you’ll have a mental model that can help you be more precise and effective.

Here is a comment that could be given as a part of some feedback, and it might look reasonable at a first glance: it seems to superficially fulfill the elements in the equation. But does it?

Not sure about the buttons’ styles and hierarchy—it feels off. Can you change them?

Observation for design feedback doesn’t just mean pointing out which part of the interface your feedback refers to, but it also refers to offering a perspective that’s as specific as possible. Are you providing the user’s perspective? Your expert perspective? A business perspective? The project manager’s perspective? A first-time user’s perspective?

When I see these two buttons, I expect one to go forward and one to go back.

Impact is about the why. Just pointing out a UI element might sometimes be enough if the issue may be obvious, but more often than not, you should add an explanation of what you’re pointing out.

When I see these two buttons, I expect one to go forward and one to go back. But this is the only screen where this happens, as before we just used a single button and an “×” to close. This seems to be breaking the consistency in the flow.

The question approach is meant to provide open guidance by eliciting the critical thinking in the designer receiving the feedback. Notably, in Lara’s equation she provides a second approach: request, which instead provides guidance toward a specific solution. While that’s a viable option for feedback in general, for design critiques, in my experience, defaulting to the question approach usually reaches the best solutions because designers are generally more comfortable in being given an open space to explore.

The difference between the two can be exemplified with, for the question approach:

When I see these two buttons, I expect one to go forward and one to go back. But this is the only screen where this happens, as before we just used a single button and an “×” to close. This seems to be breaking the consistency in the flow. Would it make sense to unify them?

Or, for the request approach:

When I see these two buttons, I expect one to go forward and one to go back. But this is the only screen where this happens, as before we just used a single button and an “×” to close. This seems to be breaking the consistency in the flow. Let’s make sure that all screens have the same pair of forward and back buttons.

At this point in some situations, it might be useful to integrate with an extra why: why you consider the given suggestion to be better.

When I see these two buttons, I expect one to go forward and one to go back. But this is the only screen where this happens, as before we just used a single button and an “×” to close. This seems to be breaking the consistency in the flow. Let’s make sure that all screens have the same two forward and back buttons so that users don’t get confused.

Choosing the question approach or the request approach can also at times be a matter of personal preference. A while ago, I was putting a lot of effort into improving my feedback: I did rounds of anonymous feedback, and I reviewed feedback with other people. After a few rounds of this work and a year later, I got a positive response: my feedback came across as effective and grounded. Until I changed teams. To my shock, my next round of feedback from one specific person wasn’t that great. The reason is that I had previously tried not to be prescriptive in my advice—because the people who I was previously working with preferred the open-ended question format over the request style of suggestions. But now in this other team, there was one person who instead preferred specific guidance. So I adapted my feedback for them to include requests.

One comment that I heard come up a few times is that this kind of feedback is quite long, and it doesn’t seem very efficient. No… but also yes. Let’s explore both sides.

No, this style of feedback is actually efficient because the length here is a byproduct of clarity, and spending time giving this kind of feedback can provide exactly enough information for a good fix. Also if we zoom out, it can reduce future back-and-forth conversations and misunderstandings, improving the overall efficiency and effectiveness of collaboration beyond the single comment. Imagine that in the example above the feedback were instead just, “Let’s make sure that all screens have the same two forward and back buttons.” The designer receiving this feedback wouldn’t have much to go by, so they might just apply the change. In later iterations, the interface might change or they might introduce new features—and maybe that change might not make sense anymore. Without the why, the designer might imagine that the change is about consistency… but what if it wasn’t? So there could now be an underlying concern that changing the buttons would be perceived as a regression.

Yes, this style of feedback is not always efficient because the points in some comments don’t always need to be exhaustive, sometimes because certain changes may be obvious (“The font used doesn’t follow our guidelines”) and sometimes because the team may have a lot of internal knowledge such that some of the whys may be implied.

So the equation above isn’t meant to suggest a strict template for feedback but a mnemonic to reflect and improve the practice. Even after years of active work on my critiques, I still from time to time go back to this formula and reflect on whether what I just wrote is effective.

The tone

Well-grounded content is the foundation of feedback, but that’s not really enough. The soft skills of the person who’s providing the critique can multiply the likelihood that the feedback will be well received and understood. Tone alone can make the difference between content that’s rejected or welcomed, and it’s been demonstrated that only positive feedback creates sustained change in people.

Since our goal is to be understood and to have a positive working environment, tone is essential to work on. Over the years, I’ve tried to summarize the required soft skills in a formula that mirrors the one for content: the receptivity equation.

Respectful feedback comes across as grounded, solid, and constructive. It’s the kind of feedback that, whether it’s positive or negative, is perceived as useful and fair.

Timing refers to when the feedback happens. To-the-point feedback doesn’t have much hope of being well received if it’s given at the wrong time. Questioning the entire high-level information architecture of a new feature when it’s about to ship might still be relevant if that questioning highlights a major blocker that nobody saw, but it’s way more likely that those concerns will have to wait for a later rework. So in general, attune your feedback to the stage of the project. Early iteration? Late iteration? Polishing work in progress? These all have different needs. The right timing will make it more likely that your feedback will be well received.

Attitude is the equivalent of intent, and in the context of person-to-person feedback, it can be referred to as radical candor. That means checking before we write to see whether what we have in mind will truly help the person and make the project better overall. This might be a hard reflection at times because maybe we don’t want to admit that we don’t really appreciate that person. Hopefully that’s not the case, but that can happen, and that’s okay. Acknowledging and owning that can help you make up for that: how would I write if I really cared about them? How can I avoid being passive aggressive? How can I be more constructive?

Form is relevant especially in a diverse and cross-cultural work environments because having great content, perfect timing, and the right attitude might not come across if the way that we write creates misunderstandings. There might be many reasons for this: sometimes certain words might trigger specific reactions; sometimes nonnative speakers might not understand all the nuances of some sentences; sometimes our brains might just be different and we might perceive the world differently—neurodiversity must be taken into consideration. Whatever the reason, it’s important to review not just what we write but how.

A few years back, I was asking for some feedback on how I give feedback. I received some good advice but also a comment that surprised me. They pointed out that when I wrote “Oh, […],” I made them feel stupid. That wasn’t my intent! I felt really bad, and I just realized that I provided feedback to them for months, and every time I might have made them feel stupid. I was horrified… but also thankful. I made a quick fix: I added “oh” in my list of replaced words (your choice between: macOS’s text replacement, aText, TextExpander, or others) so that when I typed “oh,” it was instantly deleted.

Something to highlight because it’s quite frequent—especially in teams that have a strong group spirit—is that people tend to beat around the bush. It’s important to remember here that a positive attitude doesn’t mean going light on the feedback—it just means that even when you provide hard, difficult, or challenging feedback, you do so in a way that’s respectful and constructive. The nicest thing that you can do for someone is to help them grow.

We have a great advantage in giving feedback in written form: it can be reviewed by another person who isn’t directly involved, which can help to reduce or remove any bias that might be there. I found that the best, most insightful moments for me have happened when I’ve shared a comment and I’ve asked someone who I highly trusted, “How does this sound?,” “How can I do it better,” and even “How would you have written it?”—and I’ve learned a lot by seeing the two versions side by side.

The format

Asynchronous feedback also has a major inherent advantage: we can take more time to refine what we’ve written to make sure that it fulfills two main goals: the clarity of communication and the actionability of the suggestions.

Let’s imagine that someone shared a design iteration for a project. You are reviewing it and leaving a comment. There are many ways to do this, and of course context matters, but let’s try to think about some elements that may be useful to consider.

In terms of clarity, start by grounding the critique that you’re about to give by providing context. Specifically, this means describing where you’re coming from: do you have a deep knowledge of the project, or is this the first time that you’re seeing it? Are you coming from a high-level perspective, or are you figuring out the details? Are there regressions? Which user’s perspective are you taking when providing your feedback? Is the design iteration at a point where it would be okay to ship this, or are there major things that need to be addressed first?

Providing context is helpful even if you’re sharing feedback within a team that already has some information on the project. And context is absolutely essential when giving cross-team feedback. If I were to review a design that might be indirectly related to my work, and if I had no knowledge about how the project arrived at that point, I would say so, highlighting my take as external.

We often focus on the negatives, trying to outline all the things that could be done better. That’s of course important, but it’s just as important—if not more—to focus on the positives, especially if you saw progress from the previous iteration. This might seem superfluous, but it’s important to keep in mind that design is a discipline where there are hundreds of possible solutions for every problem. So pointing out that the design solution that was chosen is good and explaining why it’s good has two major benefits: it confirms that the approach taken was solid, and it helps to ground your negative feedback. In the longer term, sharing positive feedback can help prevent regressions on things that are going well because those things will have been highlighted as important. As a bonus, positive feedback can also help reduce impostor syndrome.

There’s one powerful approach that combines both context and a focus on the positives: frame how the design is better than the status quo (compared to a previous iteration, competitors, or benchmarks) and why, and then on that foundation, you can add what could be improved. This is powerful because there’s a big difference between a critique that’s for a design that’s already in good shape and a critique that’s for a design that isn’t quite there yet.

Another way that you can improve your feedback is to depersonalize the feedback: the comments should always be about the work, never about the person who made it. It’s “This button isn’t well aligned” versus “You haven’t aligned this button well.” This is very easy to change in your writing by reviewing it just before sending.

In terms of actionability, one of the best approaches to help the designer who’s reading through your feedback is to split it into bullet points or paragraphs, which are easier to review and analyze one by one. For longer pieces of feedback, you might also consider splitting it into sections or even across multiple comments. Of course, adding screenshots or signifying markers of the specific part of the interface you’re referring to can also be especially useful.

One approach that I’ve personally used effectively in some contexts is to enhance the bullet points with four markers using emojis. So a red square 🟥 means that it’s something that I consider blocking; a yellow diamond 🔶 is something that I can be convinced otherwise, but it seems to me that it should be changed; and a green circle 🟢 is a detailed, positive confirmation. I also use a blue spiral 🌀 for either something that I’m not sure about, an exploration, an open alternative, or just a note. But I’d use this approach only on teams where I’ve already established a good level of trust because if it happens that I have to deliver a lot of red squares, the impact could be quite demoralizing, and I’d reframe how I’d communicate that a bit.

Let’s see how this would work by reusing the example that we used earlier as the first bullet point in this list:

- 🔶 Navigation—When I see these two buttons, I expect one to go forward and one to go back. But this is the only screen where this happens, as before we just used a single button and an “×” to close. This seems to be breaking the consistency in the flow. Let’s make sure that all screens have the same two forward and back buttons so that users don’t get confused.

- 🟢 Overall—I think the page is solid, and this is good enough to be our release candidate for a version 1.0.

- 🟢 Metrics—Good improvement in the buttons on the metrics area; the improved contrast and new focus style make them more accessible.

- 🟥 Button Style—Using the green accent in this context creates the impression that it’s a positive action because green is usually perceived as a confirmation color. Do we need to explore a different color?

- 🔶Tiles—Given the number of items on the page, and the overall page hierarchy, it seems to me that the tiles shouldn’t be using the Subtitle 1 style but the Subtitle 2 style. This will keep the visual hierarchy more consistent.

- 🌀 Background—Using a light texture works well, but I wonder whether it adds too much noise in this kind of page. What is the thinking in using that?

What about giving feedback directly in Figma or another design tool that allows in-place feedback? In general, I find these difficult to use because they hide discussions and they’re harder to track, but in the right context, they can be very effective. Just make sure that each of the comments is separate so that it’s easier to match each discussion to a single task, similar to the idea of splitting mentioned above.

One final note: say the obvious. Sometimes we might feel that something is obviously good or obviously wrong, and so we don’t say it. Or sometimes we might have a doubt that we don’t express because the question might sound stupid. Say it—that’s okay. You might have to reword it a little bit to make the reader feel more comfortable, but don’t hold it back. Good feedback is transparent, even when it may be obvious.

There’s another advantage of asynchronous feedback: written feedback automatically tracks decisions. Especially in large projects, “Why did we do this?” could be a question that pops up from time to time, and there’s nothing better than open, transparent discussions that can be reviewed at any time. For this reason, I recommend using software that saves these discussions, without hiding them once they are resolved.

Content, tone, and format. Each one of these subjects provides a useful model, but working to improve eight areas—observation, impact, question, timing, attitude, form, clarity, and actionability—is a lot of work to put in all at once. One effective approach is to take them one by one: first identify the area that you lack the most (either from your perspective or from feedback from others) and start there. Then the second, then the third, and so on. At first you’ll have to put in extra time for every piece of feedback that you give, but after a while, it’ll become second nature, and your impact on the work will multiply.

Thanks to Brie Anne Demkiw and Mike Shelton for reviewing the first draft of this article.

Asynchronous Design Critique: Getting Feedback

“Any comment?” is probably one of the worst ways to ask for feedback. It’s vague and open ended, and it doesn’t provide any indication of what we’re looking for. Getting good feedback starts earlier than we might expect: it starts with the request.

It might seem counterintuitive to start the process of receiving feedback with a question, but that makes sense if we realize that getting feedback can be thought of as a form of design research. In the same way that we wouldn’t do any research without the right questions to get the insights that we need, the best way to ask for feedback is also to craft sharp questions.

Design critique is not a one-shot process. Sure, any good feedback workflow continues until the project is finished, but this is particularly true for design because design work continues iteration after iteration, from a high level to the finest details. Each level needs its own set of questions.

And finally, as with any good research, we need to review what we got back, get to the core of its insights, and take action. Question, iteration, and review. Let’s look at each of those.

The question

Being open to feedback is essential, but we need to be precise about what we’re looking for. Just saying “Any comment?”, “What do you think?”, or “I’d love to get your opinion” at the end of a presentation—whether it’s in person, over video, or through a written post—is likely to get a number of varied opinions or, even worse, get everyone to follow the direction of the first person who speaks up. And then… we get frustrated because vague questions like those can turn a high-level flows review into people instead commenting on the borders of buttons. Which might be a hearty topic, so it might be hard at that point to redirect the team to the subject that you had wanted to focus on.

But how do we get into this situation? It’s a mix of factors. One is that we don’t usually consider asking as a part of the feedback process. Another is how natural it is to just leave the question implied, expecting the others to be on the same page. Another is that in nonprofessional discussions, there’s often no need to be that precise. In short, we tend to underestimate the importance of the questions, so we don’t work on improving them.

The act of asking good questions guides and focuses the critique. It’s also a form of consent: it makes it clear that you’re open to comments and what kind of comments you’d like to get. It puts people in the right mental state, especially in situations when they weren’t expecting to give feedback.

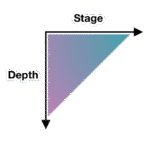

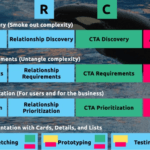

There isn’t a single best way to ask for feedback. It just needs to be specific, and specificity can take many shapes. A model for design critique that I’ve found particularly useful in my coaching is the one of stage versus depth.

“Stage” refers to each of the steps of the process—in our case, the design process. In progressing from user research to the final design, the kind of feedback evolves. But within a single step, one might still review whether some assumptions are correct and whether there’s been a proper translation of the amassed feedback into updated designs as the project has evolved. A starting point for potential questions could derive from the layers of user experience. What do you want to know: Project objectives? User needs? Functionality? Content? Interaction design? Information architecture? UI design? Navigation design? Visual design? Branding?

Here’re a few example questions that are precise and to the point that refer to different layers:

- Functionality: Is automating account creation desirable?

- Interaction design: Take a look through the updated flow and let me know whether you see any steps or error states that I might’ve missed.

- Information architecture: We have two competing bits of information on this page. Is the structure effective in communicating them both?

- UI design: What are your thoughts on the error counter at the top of the page that makes sure that you see the next error, even if the error is out of the viewport?

- Navigation design: From research, we identified these second-level navigation items, but once you’re on the page, the list feels too long and hard to navigate. Are there any suggestions to address this?

- Visual design: Are the sticky notifications in the bottom-right corner visible enough?

The other axis of specificity is about how deep you’d like to go on what’s being presented. For example, we might have introduced a new end-to-end flow, but there was a specific view that you found particularly challenging and you’d like a detailed review of that. This can be especially useful from one iteration to the next where it’s important to highlight the parts that have changed.

There are other things that we can consider when we want to achieve more specific—and more effective—questions.

A simple trick is to remove generic qualifiers from your questions like “good,” “well,” “nice,” “bad,” “okay,” and “cool.” For example, asking, “When the block opens and the buttons appear, is this interaction good?” might look specific, but you can spot the “good” qualifier, and convert it to an even better question: “When the block opens and the buttons appear, is it clear what the next action is?”

Sometimes we actually do want broad feedback. That’s rare, but it can happen. In that sense, you might still make it explicit that you’re looking for a wide range of opinions, whether at a high level or with details. Or maybe just say, “At first glance, what do you think?” so that it’s clear that what you’re asking is open ended but focused on someone’s impression after their first five seconds of looking at it.

Sometimes the project is particularly expansive, and some areas may have already been explored in detail. In these situations, it might be useful to explicitly say that some parts are already locked in and aren’t open to feedback. It’s not something that I’d recommend in general, but I’ve found it useful to avoid falling again into rabbit holes of the sort that might lead to further refinement but aren’t what’s most important right now.

Asking specific questions can completely change the quality of the feedback that you receive. People with less refined critique skills will now be able to offer more actionable feedback, and even expert designers will welcome the clarity and efficiency that comes from focusing only on what’s needed. It can save a lot of time and frustration.

The iteration

Design iterations are probably the most visible part of the design work, and they provide a natural checkpoint for feedback. Yet a lot of design tools with inline commenting tend to show changes as a single fluid stream in the same file, and those types of design tools make conversations disappear once they’re resolved, update shared UI components automatically, and compel designs to always show the latest version—unless these would-be helpful features were to be manually turned off. The implied goal that these design tools seem to have is to arrive at just one final copy with all discussions closed, probably because they inherited patterns from how written documents are collaboratively edited. That’s probably not the best way to approach design critiques, but even if I don’t want to be too prescriptive here: that could work for some teams.

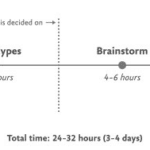

The asynchronous design-critique approach that I find most effective is to create explicit checkpoints for discussion. I’m going to use the term iteration post for this. It refers to a write-up or presentation of the design iteration followed by a discussion thread of some kind. Any platform that can accommodate this structure can use this. By the way, when I refer to a “write-up or presentation,” I’m including video recordings or other media too: as long as it’s asynchronous, it works.

Using iteration posts has many advantages:

- It creates a rhythm in the design work so that the designer can review feedback from each iteration and prepare for the next.

- It makes decisions visible for future review, and conversations are likewise always available.

- It creates a record of how the design changed over time.

- Depending on the tool, it might also make it easier to collect feedback and act on it.

These posts of course don’t mean that no other feedback approach should be used, just that iteration posts could be the primary rhythm for a remote design team to use. And other feedback approaches (such as live critique, pair designing, or inline comments) can build from there.

I don’t think there’s a standard format for iteration posts. But there are a few high-level elements that make sense to include as a baseline:

- The goal

- The design

- The list of changes

- The questions

Each project is likely to have a goal, and hopefully it’s something that’s already been summarized in a single sentence somewhere else, such as the client brief, the product manager’s outline, or the project owner’s request. So this is something that I’d repeat in every iteration post—literally copy and pasting it. The idea is to provide context and to repeat what’s essential to make each iteration post complete so that there’s no need to find information spread across multiple posts. If I want to know about the latest design, the latest iteration post will have all that I need.

This copy-and-paste part introduces another relevant concept: alignment comes from repetition. So having posts that repeat information is actually very effective toward making sure that everyone is on the same page.

The design is then the actual series of information-architecture outlines, diagrams, flows, maps, wireframes, screens, visuals, and any other kind of design work that’s been done. In short, it’s any design artifact. For the final stages of work, I prefer the term blueprint to emphasize that I’ll be showing full flows instead of individual screens to make it easier to understand the bigger picture.

It can also be useful to label the artifacts with clear titles because that can make it easier to refer to them. Write the post in a way that helps people understand the work. It’s not too different from organizing a good live presentation.

For an efficient discussion, you should also include a bullet list of the changes from the previous iteration to let people focus on what’s new, which can be especially useful for larger pieces of work where keeping track, iteration after iteration, could become a challenge.

And finally, as noted earlier, it’s essential that you include a list of the questions to drive the design critique in the direction you want. Doing this as a numbered list can also help make it easier to refer to each question by its number.

Not all iterations are the same. Earlier iterations don’t need to be as tightly focused—they can be more exploratory and experimental, maybe even breaking some of the design-language guidelines to see what’s possible. Then later, the iterations start settling on a solution and refining it until the design process reaches its end and the feature ships.

I want to highlight that even if these iteration posts are written and conceived as checkpoints, by no means do they need to be exhaustive. A post might be a draft—just a concept to get a conversation going—or it could be a cumulative list of each feature that was added over the course of each iteration until the full picture is done.

Over time, I also started using specific labels for incremental iterations: i1, i2, i3, and so on. This might look like a minor labelling tip, but it can help in multiple ways:

- Unique—It’s a clear unique marker. Within each project, one can easily say, “This was discussed in i4,” and everyone knows where they can go to review things.

- Unassuming—It works like versions (such as v1, v2, and v3) but in contrast, versions create the impression of something that’s big, exhaustive, and complete. Iterations must be able to be exploratory, incomplete, partial.

- Future proof—It resolves the “final” naming problem that you can run into with versions. No more files named “final final complete no-really-its-done.” Within each project, the largest number always represents the latest iteration.

To mark when a design is complete enough to be worked on, even if there might be some bits still in need of attention and in turn more iterations needed, the wording release candidate (RC) could be used to describe it: “with i8, we reached RC” or “i12 is an RC.”

The review

What usually happens during a design critique is an open discussion, with a back and forth between people that can be very productive. This approach is particularly effective during live, synchronous feedback. But when we work asynchronously, it’s more effective to use a different approach: we can shift to a user-research mindset. Written feedback from teammates, stakeholders, or others can be treated as if it were the result of user interviews and surveys, and we can analyze it accordingly.

This shift has some major benefits that make asynchronous feedback particularly effective, especially around these friction points:

- It removes the pressure to reply to everyone.

- It reduces the frustration from swoop-by comments.

- It lessens our personal stake.

The first friction point is feeling a pressure to reply to every single comment. Sometimes we write the iteration post, and we get replies from our team. It’s just a few of them, it’s easy, and it doesn’t feel like a problem. But other times, some solutions might require more in-depth discussions, and the amount of replies can quickly increase, which can create a tension between trying to be a good team player by replying to everyone and doing the next design iteration. This might be especially true if the person who’s replying is a stakeholder or someone directly involved in the project who we feel that we need to listen to. We need to accept that this pressure is absolutely normal, and it’s human nature to try to accommodate people who we care about. Sometimes replying to all comments can be effective, but if we treat a design critique more like user research, we realize that we don’t have to reply to every comment, and in asynchronous spaces, there are alternatives:

- One is to let the next iteration speak for itself. When the design evolves and we post a follow-up iteration, that’s the reply. You might tag all the people who were involved in the previous discussion, but even that’s a choice, not a requirement.

- Another is to briefly reply to acknowledge each comment, such as “Understood. Thank you,” “Good points—I’ll review,” or “Thanks. I’ll include these in the next iteration.” In some cases, this could also be just a single top-level comment along the lines of “Thanks for all the feedback everyone—the next iteration is coming soon!”

- Another is to provide a quick summary of the comments before moving on. Depending on your workflow, this can be particularly useful as it can provide a simplified checklist that you can then use for the next iteration.

The second friction point is the swoop-by comment, which is the kind of feedback that comes from someone outside the project or team who might not be aware of the context, restrictions, decisions, or requirements—or of the previous iterations’ discussions. On their side, there’s something that one can hope that they might learn: they could start to acknowledge that they’re doing this and they could be more conscious in outlining where they’re coming from. Swoop-by comments often trigger the simple thought “We’ve already discussed this…”, and it can be frustrating to have to repeat the same reply over and over.

Let’s begin by acknowledging again that there’s no need to reply to every comment. If, however, replying to a previously litigated point might be useful, a short reply with a link to the previous discussion for extra details is usually enough. Remember, alignment comes from repetition, so it’s okay to repeat things sometimes!

Swoop-by commenting can still be useful for two reasons: they might point out something that still isn’t clear, and they also have the potential to stand in for the point of view of a user who’s seeing the design for the first time. Sure, you’ll still be frustrated, but that might at least help in dealing with it.

The third friction point is the personal stake we could have with the design, which could make us feel defensive if the review were to feel more like a discussion. Treating feedback as user research helps us create a healthy distance between the people giving us feedback and our ego (because yes, even if we don’t want to admit it, it’s there). And ultimately, treating everything in aggregated form allows us to better prioritize our work.

Always remember that while you need to listen to stakeholders, project owners, and specific advice, you don’t have to accept every piece of feedback. You have to analyze it and make a decision that you can justify, but sometimes “no” is the right answer.

As the designer leading the project, you’re in charge of that decision. Ultimately, everyone has their specialty, and as the designer, you’re the one who has the most knowledge and the most context to make the right decision. And by listening to the feedback that you’ve received, you’re making sure that it’s also the best and most balanced decision.

Thanks to Brie Anne Demkiw and Mike Shelton for reviewing the first draft of this article.

Designing for the Unexpected

I’m not sure when I first heard this quote, but it’s something that has stayed with me over the years. How do you create services for situations you can’t imagine? Or design products that work on devices yet to be invented?

Flash, Photoshop, and responsive design

When I first started designing websites, my go-to software was Photoshop. I created a 960px canvas and set about creating a layout that I would later drop content in. The development phase was about attaining pixel-perfect accuracy using fixed widths, fixed heights, and absolute positioning.

Ethan Marcotte’s talk at An Event Apart and subsequent article “Responsive Web Design” in A List Apart in 2010 changed all this. I was sold on responsive design as soon as I heard about it, but I was also terrified. The pixel-perfect designs full of magic numbers that I had previously prided myself on producing were no longer good enough.

The fear wasn’t helped by my first experience with responsive design. My first project was to take an existing fixed-width website and make it responsive. What I learned the hard way was that you can’t just add responsiveness at the end of a project. To create fluid layouts, you need to plan throughout the design phase.

A new way to design

Designing responsive or fluid sites has always been about removing limitations, producing content that can be viewed on any device. It relies on the use of percentage-based layouts, which I initially achieved with native CSS and utility classes:

.column-span-6 {

width: 49%;

float: left;

margin-right: 0.5%;

margin-left: 0.5%;

}

.column-span-4 {

width: 32%;

float: left;

margin-right: 0.5%;

margin-left: 0.5%;

}

.column-span-3 {

width: 24%;

float: left;

margin-right: 0.5%;

margin-left: 0.5%;

}Then with Sass so I could take advantage of @includes to re-use repeated blocks of code and move back to more semantic markup:

.logo {

@include colSpan(6);

}

.search {

@include colSpan(3);

}

.social-share {

@include colSpan(3);

}Media queries

The second ingredient for responsive design is media queries. Without them, content would shrink to fit the available space regardless of whether that content remained readable (The exact opposite problem occurred with the introduction of a mobile-first approach).

Media queries prevented this by allowing us to add breakpoints where the design could adapt. Like most people, I started out with three breakpoints: one for desktop, one for tablets, and one for mobile. Over the years, I added more and more for phablets, wide screens, and so on.

For years, I happily worked this way and improved both my design and front-end skills in the process. The only problem I encountered was making changes to content, since with our Sass grid system in place, there was no way for the site owners to add content without amending the markup—something a small business owner might struggle with. This is because each row in the grid was defined using a div as a container. Adding content meant creating new row markup, which requires a level of HTML knowledge.

Row markup was a staple of early responsive design, present in all the widely used frameworks like Bootstrap and Skeleton.

1 of 7

2 of 7

3 of 7

4 of 7

5 of 7

6 of 7

7 of 7

Another problem arose as I moved from a design agency building websites for small- to medium-sized businesses, to larger in-house teams where I worked across a suite of related sites. In those roles I started to work much more with reusable components.

Our reliance on media queries resulted in components that were tied to common viewport sizes. If the goal of component libraries is reuse, then this is a real problem because you can only use these components if the devices you’re designing for correspond to the viewport sizes used in the pattern library—in the process not really hitting that “devices that don’t yet exist” goal.

Then there’s the problem of space. Media queries allow components to adapt based on the viewport size, but what if I put a component into a sidebar, like in the figure below?

Container queries: our savior or a false dawn?

Container queries have long been touted as an improvement upon media queries, but at the time of writing are unsupported in most browsers. There are JavaScript workarounds, but they can create dependency and compatibility issues. The basic theory underlying container queries is that elements should change based on the size of their parent container and not the viewport width, as seen in the following illustrations.

One of the biggest arguments in favor of container queries is that they help us create components or design patterns that are truly reusable because they can be picked up and placed anywhere in a layout. This is an important step in moving toward a form of component-based design that works at any size on any device.

In other words, responsive components to replace responsive layouts.

Container queries will help us move from designing pages that respond to the browser or device size to designing components that can be placed in a sidebar or in the main content, and respond accordingly.

My concern is that we are still using layout to determine when a design needs to adapt. This approach will always be restrictive, as we will still need pre-defined breakpoints. For this reason, my main question with container queries is, How would we decide when to change the CSS used by a component?

A component library removed from context and real content is probably not the best place for that decision.

As the diagrams below illustrate, we can use container queries to create designs for specific container widths, but what if I want to change the design based on the image size or ratio?

In this example, the dimensions of the container are not what should dictate the design; rather, the image is.

It’s hard to say for sure whether container queries will be a success story until we have solid cross-browser support for them. Responsive component libraries would definitely evolve how we design and would improve the possibilities for reuse and design at scale. But maybe we will always need to adjust these components to suit our content.

CSS is changing

Whilst the container query debate rumbles on, there have been numerous advances in CSS that change the way we think about design. The days of fixed-width elements measured in pixels and floated div elements used to cobble layouts together are long gone, consigned to history along with table layouts. Flexbox and CSS Grid have revolutionized layouts for the web. We can now create elements that wrap onto new rows when they run out of space, not when the device changes.

.wrapper {

display: grid;

grid-template-columns: repeat(auto-fit, 450px);

gap: 10px;

}The repeat() function paired with auto-fit or auto-fill allows us to specify how much space each column should use while leaving it up to the browser to decide when to spill the columns onto a new line. Similar things can be achieved with Flexbox, as elements can wrap over multiple rows and “flex” to fill available space.

.wrapper {

display: flex;

flex-wrap: wrap;

justify-content: space-between;

}

.child {

flex-basis: 32%;

margin-bottom: 20px;

}The biggest benefit of all this is you don’t need to wrap elements in container rows. Without rows, content isn’t tied to page markup in quite the same way, allowing for removals or additions of content without additional development.

This is a big step forward when it comes to creating designs that allow for evolving content, but the real game changer for flexible designs is CSS Subgrid.

Remember the days of crafting perfectly aligned interfaces, only for the customer to add an unbelievably long header almost as soon as they’re given CMS access, like the illustration below?

Subgrid allows elements to respond to adjustments in their own content and in the content of sibling elements, helping us create designs more resilient to change.

.wrapper {

display: grid;

grid-template-columns: repeat(auto-fit, minmax(150px, 1fr));

grid-template-rows: auto 1fr auto;

gap: 10px;

}

.sub-grid {

display: grid;

grid-row: span 3;

grid-template-rows: subgrid; /* sets rows to parent grid */

}CSS Grid allows us to separate layout and content, thereby enabling flexible designs. Meanwhile, Subgrid allows us to create designs that can adapt in order to suit morphing content. Subgrid at the time of writing is only supported in Firefox but the above code can be implemented behind an @supports feature query.

Intrinsic layouts

I’d be remiss not to mention intrinsic layouts, the term created by Jen Simmons to describe a mixture of new and old CSS features used to create layouts that respond to available space.

Responsive layouts have flexible columns using percentages. Intrinsic layouts, on the other hand, use the fr unit to create flexible columns that won’t ever shrink so much that they render the content illegible.

fr units is a way to say I want you to distribute the extra space in this way, but…don’t ever make it smaller than the content that’s inside of it.

—Jen Simmons, “Designing Intrinsic Layouts”

Intrinsic layouts can also utilize a mixture of fixed and flexible units, allowing the content to dictate the space it takes up.

What makes intrinsic design stand out is that it not only creates designs that can withstand future devices but also helps scale design without losing flexibility. Components and patterns can be lifted and reused without the prerequisite of having the same breakpoints or the same amount of content as in the previous implementation.

We can now create designs that adapt to the space they have, the content within them, and the content around them. With an intrinsic approach, we can construct responsive components without depending on container queries.

Another 2010 moment?

This intrinsic approach should in my view be every bit as groundbreaking as responsive web design was ten years ago. For me, it’s another “everything changed” moment.

But it doesn’t seem to be moving quite as fast; I haven’t yet had that same career-changing moment I had with responsive design, despite the widely shared and brilliant talk that brought it to my attention.

One reason for that could be that I now work in a large organization, which is quite different from the design agency role I had in 2010. In my agency days, every new project was a clean slate, a chance to try something new. Nowadays, projects use existing tools and frameworks and are often improvements to existing websites with an existing codebase.

Another could be that I feel more prepared for change now. In 2010 I was new to design in general; the shift was frightening and required a lot of learning. Also, an intrinsic approach isn’t exactly all-new; it’s about using existing skills and existing CSS knowledge in a different way.

You can’t framework your way out of a content problem

Another reason for the slightly slower adoption of intrinsic design could be the lack of quick-fix framework solutions available to kick-start the change.

Responsive grid systems were all over the place ten years ago. With a framework like Bootstrap or Skeleton, you had a responsive design template at your fingertips.

Intrinsic design and frameworks do not go hand in hand quite so well because the benefit of having a selection of units is a hindrance when it comes to creating layout templates. The beauty of intrinsic design is combining different units and experimenting with techniques to get the best for your content.

And then there are design tools. We probably all, at some point in our careers, used Photoshop templates for desktop, tablet, and mobile devices to drop designs in and show how the site would look at all three stages.

How do you do that now, with each component responding to content and layouts flexing as and when they need to? This type of design must happen in the browser, which personally I’m a big fan of.

The debate about “whether designers should code” is another that has rumbled on for years. When designing a digital product, we should, at the very least, design for a best- and worst-case scenario when it comes to content. To do this in a graphics-based software package is far from ideal. In code, we can add longer sentences, more radio buttons, and extra tabs, and watch in real time as the design adapts. Does it still work? Is the design too reliant on the current content?

Personally, I look forward to the day intrinsic design is the standard for design, when a design component can be truly flexible and adapt to both its space and content with no reliance on device or container dimensions.

Content first

Content is not constant. After all, to design for the unknown or unexpected we need to account for content changes like our earlier Subgrid card example that allowed the cards to respond to adjustments to their own content and the content of sibling elements.

Thankfully, there’s more to CSS than layout, and plenty of properties and values can help us put content first. Subgrid and pseudo-elements like ::first-line and ::first-letter help to separate design from markup so we can create designs that allow for changes.

Instead of old markup hacks like this—

First line of text with different styling...

—we can target content based on where it appears.

.element::first-line {

font-size: 1.4em;

}

.element::first-letter {

color: red;

}Much bigger additions to CSS include logical properties, which change the way we construct designs using logical dimensions (start and end) instead of physical ones (left and right), something CSS Grid also does with functions like min(), max(), and clamp().

This flexibility allows for directional changes according to content, a common requirement when we need to present content in multiple languages. In the past, this was often achieved with Sass mixins but was often limited to switching from left-to-right to right-to-left orientation.

In the Sass version, directional variables need to be set.

$direction: rtl;

$opposite-direction: ltr;

$start-direction: right;

$end-direction: left;These variables can be used as values—

body {

direction: $direction;

text-align: $start-direction;

}—or as properties.

margin-#{$end-direction}: 10px;

padding-#{$start-direction}: 10px;However, now we have native logical properties, removing the reliance on both Sass (or a similar tool) and pre-planning that necessitated using variables throughout a codebase. These properties also start to break apart the tight coupling between a design and strict physical dimensions, creating more flexibility for changes in language and in direction.

margin-block-end: 10px;

padding-block-start: 10px;There are also native start and end values for properties like text-align, which means we can replace text-align: right with text-align: start.

Like the earlier examples, these properties help to build out designs that aren’t constrained to one language; the design will reflect the content’s needs.

Fixed and fluid

We briefly covered the power of combining fixed widths with fluid widths with intrinsic layouts. The min() and max() functions are a similar concept, allowing you to specify a fixed value with a flexible alternative.

For min() this means setting a fluid minimum value and a maximum fixed value.

.element {

width: min(50%, 300px);

}The element in the figure above will be 50% of its container as long as the element’s width doesn’t exceed 300px.

For max() we can set a flexible max value and a minimum fixed value.

.element {

width: max(50%, 300px);

}Now the element will be 50% of its container as long as the element’s width is at least 300px. This means we can set limits but allow content to react to the available space.

The clamp() function builds on this by allowing us to set a preferred value with a third parameter. Now we can allow the element to shrink or grow if it needs to without getting to a point where it becomes unusable.

.element {

width: clamp(300px, 50%, 600px);

}This time, the element’s width will be 50% (the preferred value) of its container but never less than 300px and never more than 600px.

With these techniques, we have a content-first approach to responsive design. We can separate content from markup, meaning the changes users make will not affect the design. We can start to future-proof designs by planning for unexpected changes in language or direction. And we can increase flexibility by setting desired dimensions alongside flexible alternatives, allowing for more or less content to be displayed correctly.

Situation first

Thanks to what we’ve discussed so far, we can cover device flexibility by changing our approach, designing around content and space instead of catering to devices. But what about that last bit of Jeffrey Zeldman’s quote, “…situations you haven’t imagined”?

It’s a very different thing to design for someone seated at a desktop computer as opposed to someone using a mobile phone and moving through a crowded street in glaring sunshine. Situations and environments are hard to plan for or predict because they change as people react to their own unique challenges and tasks.

This is why choice is so important. One size never fits all, so we need to design for multiple scenarios to create equal experiences for all our users.

Thankfully, there is a lot we can do to provide choice.

Responsible design

“There are parts of the world where mobile data is prohibitively expensive, and where there is little or no broadband infrastructure.”

“I Used the Web for a Day on a 50 MB Budget”

Chris Ashton

One of the biggest assumptions we make is that people interacting with our designs have a good wifi connection and a wide screen monitor. But in the real world, our users may be commuters traveling on trains or other forms of transport using smaller mobile devices that can experience drops in connectivity. There is nothing more frustrating than a web page that won’t load, but there are ways we can help users use less data or deal with sporadic connectivity.

The srcset attribute allows the browser to decide which image to serve. This means we can create smaller ‘cropped’ images to display on mobile devices in turn using less bandwidth and less data.

The preload attribute can also help us to think about how and when media is downloaded. It can be used to tell a browser about any critical assets that need to be downloaded with high priority, improving perceived performance and the user experience.

There’s also native lazy loading, which indicates assets that should only be downloaded when they are needed.

With srcset, preload, and lazy loading, we can start to tailor a user’s experience based on the situation they find themselves in. What none of this does, however, is allow the user themselves to decide what they want downloaded, as the decision is usually the browser’s to make.

So how can we put users in control?

The return of media queries

Media queries have always been about much more than device sizes. They allow content to adapt to different situations, with screen size being just one of them.

We’ve long been able to check for media types like print and speech and features such as hover, resolution, and color. These checks allow us to provide options that suit more than one scenario; it’s less about one-size-fits-all and more about serving adaptable content.

As of this writing, the Media Queries Level 5 spec is still under development. It introduces some really exciting queries that in the future will help us design for multiple other unexpected situations.

For example, there’s a light-level feature that allows you to modify styles if a user is in sunlight or darkness. Paired with custom properties, these features allow us to quickly create designs or themes for specific environments.

@media (light-level: normal) {

--background-color: #fff;

--text-color: #0b0c0c;

}

@media (light-level: dim) {

--background-color: #efd226;

--text-color: #0b0c0c;

}Another key feature of the Level 5 spec is personalization. Instead of creating designs that are the same for everyone, users can choose what works for them. This is achieved by using features like prefers-reduced-data, prefers-color-scheme, and prefers-reduced-motion, the latter two of which already enjoy broad browser support. These features tap into preferences set via the operating system or browser so people don’t have to spend time making each site they visit more usable.

Media queries like this go beyond choices made by a browser to grant more control to the user.

Expect the unexpected

In the end, the one thing we should always expect is for things to change. Devices in particular change faster than we can keep up, with foldable screens already on the market.

We can’t design the same way we have for this ever-changing landscape, but we can design for content. By putting content first and allowing that content to adapt to whatever space surrounds it, we can create more robust, flexible designs that increase the longevity of our products.

A lot of the CSS discussed here is about moving away from layouts and putting content at the heart of design. From responsive components to fixed and fluid units, there is so much more we can do to take a more intrinsic approach. Even better, we can test these techniques during the design phase by designing in-browser and watching how our designs adapt in real-time.

When it comes to unexpected situations, we need to make sure our products are usable when people need them, whenever and wherever that might be. We can move closer to achieving this by involving users in our design decisions, by creating choice via browsers, and by giving control to our users with user-preference-based media queries.

Good design for the unexpected should allow for change, provide choice, and give control to those we serve: our users themselves.

Voice Content and Usability

We’ve been having conversations for thousands of years. Whether to convey information, conduct transactions, or simply to check in on one another, people have yammered away, chattering and gesticulating, through spoken conversation for countless generations. Only in the last few millennia have we begun to commit our conversations to writing, and only in the last few decades have we begun to outsource them to the computer, a machine that shows much more affinity for written correspondence than for the slangy vagaries of spoken language.

Computers have trouble because between spoken and written language, speech is more primordial. To have successful conversations with us, machines must grapple with the messiness of human speech: the disfluencies and pauses, the gestures and body language, and the variations in word choice and spoken dialect that can stymie even the most carefully crafted human-computer interaction. In the human-to-human scenario, spoken language also has the privilege of face-to-face contact, where we can readily interpret nonverbal social cues.

In contrast, written language immediately concretizes as we commit it to record and retains usages long after they become obsolete in spoken communication (the salutation “To whom it may concern,” for example), generating its own fossil record of outdated terms and phrases. Because it tends to be more consistent, polished, and formal, written text is fundamentally much easier for machines to parse and understand.

Spoken language has no such luxury. Besides the nonverbal cues that decorate conversations with emphasis and emotional context, there are also verbal cues and vocal behaviors that modulate conversation in nuanced ways: how something is said, not what. Whether rapid-fire, low-pitched, or high-decibel, whether sarcastic, stilted, or sighing, our spoken language conveys much more than the written word could ever muster. So when it comes to voice interfaces—the machines we conduct spoken conversations with—we face exciting challenges as designers and content strategists.

Voice Interactions

We interact with voice interfaces for a variety of reasons, but according to Michael McTear, Zoraida Callejas, and David Griol in The Conversational Interface, those motivations by and large mirror the reasons we initiate conversations with other people, too (). Generally, we start up a conversation because:

- we need something done (such as a transaction),

- we want to know something (information of some sort), or

- we are social beings and want someone to talk to (conversation for conversation’s sake).

These three categories—which I call transactional, informational, and prosocial—also characterize essentially every voice interaction: a single conversation from beginning to end that realizes some outcome for the user, starting with the voice interface’s first greeting and ending with the user exiting the interface. Note here that a conversation in our human sense—a chat between people that leads to some result and lasts an arbitrary length of time—could encompass multiple transactional, informational, and prosocial voice interactions in succession. In other words, a voice interaction is a conversation, but a conversation is not necessarily a single voice interaction.

Purely prosocial conversations are more gimmicky than captivating in most voice interfaces, because machines don’t yet have the capacity to really want to know how we’re doing and to do the sort of glad-handing humans crave. There’s also ongoing debate as to whether users actually prefer the sort of organic human conversation that begins with a prosocial voice interaction and shifts seamlessly into other types. In fact, in Voice User Interface Design, Michael Cohen, James Giangola, and Jennifer Balogh recommend sticking to users’ expectations by mimicking how they interact with other voice interfaces rather than trying too hard to be human—potentially alienating them in the process ().

That leaves two genres of conversations we can have with one another that a voice interface can easily have with us, too: a transactional voice interaction realizing some outcome (“buy iced tea”) and an informational voice interaction teaching us something new (“discuss a musical”).

Transactional voice interactions

Unless you’re tapping buttons on a food delivery app, you’re generally having a conversation—and therefore a voice interaction—when you order a Hawaiian pizza with extra pineapple. Even when we walk up to the counter and place an order, the conversation quickly pivots from an initial smattering of neighborly small talk to the real mission at hand: ordering a pizza (generously topped with pineapple, as it should be).

Alison: Hey, how’s it going?

Burhan: Hi, welcome to Crust Deluxe! It’s cold out there. How can I help you?

Alison: Can I get a Hawaiian pizza with extra pineapple?

Burhan: Sure, what size?

Alison: Large.

Burhan: Anything else?

Alison: No thanks, that’s it.

Burhan: Something to drink?

Alison: I’ll have a bottle of Coke.

Burhan: You got it. That’ll be $13.55 and about fifteen minutes.

Each progressive disclosure in this transactional conversation reveals more and more of the desired outcome of the transaction: a service rendered or a product delivered. Transactional conversations have certain key traits: they’re direct, to the point, and economical. They quickly dispense with pleasantries.

Informational voice interactions

Meanwhile, some conversations are primarily about obtaining information. Though Alison might visit Crust Deluxe with the sole purpose of placing an order, she might not actually want to walk out with a pizza at all. She might be just as interested in whether they serve halal or kosher dishes, gluten-free options, or something else. Here, though we again have a prosocial mini-conversation at the beginning to establish politeness, we’re after much more.

Alison: Hey, how’s it going?

Burhan: Hi, welcome to Crust Deluxe! It’s cold out there. How can I help you?

Alison: Can I ask a few questions?

Burhan: Of course! Go right ahead.

Alison: Do you have any halal options on the menu?

Burhan: Absolutely! We can make any pie halal by request. We also have lots of vegetarian, ovo-lacto, and vegan options. Are you thinking about any other dietary restrictions?

Alison: What about gluten-free pizzas?

Burhan: We can definitely do a gluten-free crust for you, no problem, for both our deep-dish and thin-crust pizzas. Anything else I can answer for you?

Alison: That’s it for now. Good to know. Thanks!

Burhan: Anytime, come back soon!

This is a very different dialogue. Here, the goal is to get a certain set of facts. Informational conversations are investigative quests for the truth—research expeditions to gather data, news, or facts. Voice interactions that are informational might be more long-winded than transactional conversations by necessity. Responses tend to be lengthier, more informative, and carefully communicated so the customer understands the key takeaways.

Voice Interfaces