How to Create Exceptional Experiences

How to Create Exceptional Experiences written by John Jantsch read more at Duct Tape Marketing

Listen to the full episode: Overview On this episode of the Duct Tape Marketing Podcast, John Jantsch interviews Neen James, globally recognized leadership and customer experience expert, keynote speaker, and author of “Exceptional Experiences: Five Luxury Levers to Elevate Every Aspect of Your Business.” Neen shares how any business—regardless of size, industry, or budget—can […]

How to Create Exceptional Experiences written by John Jantsch read more at Duct Tape Marketing

![Photo of Neen James]() Overview

Overview

On this episode of the Duct Tape Marketing Podcast, John Jantsch interviews Neen James, globally recognized leadership and customer experience expert, keynote speaker, and author of “Exceptional Experiences: Five Luxury Levers to Elevate Every Aspect of Your Business.” Neen shares how any business—regardless of size, industry, or budget—can create extraordinary, memorable customer experiences by leveraging attention, intentionality, and five key “luxury levers.” From the power of origin stories to practical experience audits, Neen unpacks how luxury is a feeling, not a price tag—and why making people feel seen, heard, and valued is the greatest differentiator in a world full of automation and noise.

About the Guest

Neen James is a leadership and customer experience expert, keynote speaker, and author known for helping Fortune 500s and fast-growth businesses turn ordinary interactions into extraordinary results. Her frameworks focus on attention, intentionality, and leveraging luxury “levers” to make brands more memorable, profitable, and impactful.

- Website & Free Assessment: neenjames.com

- Book: Exceptional Experiences: Five Luxury Levers to Elevate Every Aspect of Your Business

Actionable Insights

- Luxury isn’t about price or exclusivity—it’s about how you make people feel; exceptional experiences are defined as high quality, long lasting, unique, authentic, and (sometimes) indulgent.

- Any business can use the five luxury levers—Attention, Anticipation, Personalization, Generosity, and Gratitude—to elevate customer experiences.

- Attention is about presence, storytelling, and meaningful origin stories, not just being loud; collaborations and origin stories are powerful ways to capture mindshare.

- Anticipation is the hallmark of luxury: Think like a concierge, not a bellhop—anticipate client needs before they ask.

- Personalization and customization are rooted in genuine curiosity and fascination with your customers—capture details and use them to create more tailored experiences.

- Engage all five senses—luxury is often subtle, seamless, and easy; even digital businesses can use the language of the senses to stand out.

- Experience audits (and mystery shopping) are practical ways to spot where your business falls short of luxury and to inspire your team to elevate every touchpoint.

- In an automated world, human touches—like handwritten notes, personalized videos, or exclusive small events—are more valuable and memorable than ever.

- Differentiation often comes from surprising luxury in unexpected places—when you deliver above-and-beyond experiences where clients least expect it.

- Start small: Engage the senses, be truly present, and look for one way to add delight, anticipation, or a personal touch in the next 30 days.

Great Moments (with Timestamps)

- 01:17 – Redefining “Luxury” for Every Business

Why luxury is both inclusive and exclusive—and always about feelings, not price. - 03:47 – What Does Luxury Really Mean?

The five universal qualities: high quality, long lasting, unique, authentic, indulgent. - 04:36 – The Five Luxury Levers Explained

From attention to advocacy, Neen’s elevation model for mindshare and market share. - 06:32 – Capturing Attention Through Origin Stories and Collaboration

Why being present, telling powerful stories, and creative partnerships win in a noisy world. - 08:54 – Anticipation as the Hallmark of Luxury

Learning from the concierge: how to anticipate needs and create wow moments. - 12:13 – Experience Audits and Mystery Shopping

Practical ways to spot and fix gaps in your customer journey. - 15:48 – The Power of the Five Senses

How fragrance, tactile experiences, and even digital “sense” can elevate your brand. - 17:37 – Human Touch in an Automated World

Handwritten notes, personalized videos, and thoughtful gifts drive real connection. - 21:21 – Differentiation Through Unexpected Luxury

Why luxury in “ordinary” businesses creates the most powerful word-of-mouth.

Insights

“Luxury is about making people feel seen, heard, and valued—no matter the price tag.”

“Anticipation is what sets luxury apart; be curious, ask questions, and solve needs before they’re spoken.”

“Engage the senses—luxury is as much about ease, atmosphere, and emotion as it is about products.”

“In a digital and automated world, human touches and surprise-and-delight moments are your top differentiators.”

“Start small: pick one luxury lever and look for ways to add a personal or sensory touch to your next customer interaction.”

John Jantsch (00:01.464)

Hello and welcome to another episode of the Duct Tape Marketing Podcast. This is John Jantsch and my guest today is Neen James. She is a globally recognized leadership and customer experience expert, sought after keynote speaker and author. She has worked with Fortune 500 companies and fast growth businesses alike, helping them turn ordinary interactions into extraordinary results with a focus on…

Neen (00:06.681)

is today is Neen James. She’s a globally.

Neen (00:14.203)

keynote speaker and author. She has worked with Fortune 500 companies and fast growth businesses alike, helping them turn ordinary interactions into extraordinary results with a focus on attention, intentionality, and luxury levers that we’re going talk about today. She’s passionate about making businesses more memorable, profitable, and impactful. And we are going to unpack her latest book, Exceptional Experiences by Luxury Levers to Elevate

John Jantsch (00:26.592)

attention, intentionality, and luxury levers that we’re going to talk about today. he’s passionate about making businesses more memorable, profitable, and impactful. And we are going to unpack her latest book, Exceptional Experiences, Five Luxury Levers to Elevate Every Aspect of Your Business. So Neen, welcome back.

Neen (00:44.571)

of your business, Dean, welcome back. G’day, what a treat it is to be back with you. It’s been a minute since we got to play like this.

John Jantsch (00:52.682)

That’s right. So you we need to start here, I think, because you kind of opened the book by saying, OK, let’s talk about this word luxury, what it actually is. Right. Because I think we think Ritz Carlton, we think Rolex, we think Mercedes, whatever. I’m not sure those are the most luxurious brands, but you get the point that that’s how people think. So if I’m an accounting firm or I’m a remodeling contractor, like what does luxury have to do with me?

Neen (01:00.303)

Mm-hmm.

Neen (01:04.705)

Sure.

Neen (01:17.485)

Yeah, think luxury is a divisive word, John. I think to your point, some people think it’s expensive or it’s elitist or it’s unapproachable. And yet I’m on this mission to really reframe and change the narrative around that. It’s my belief that luxury is both inclusive and exclusive. So inclusive, John, meaning I think luxury is for everyone every day. It’s just that our definitions of luxury are different. We can get into that.

John Jantsch (01:20.492)

Yeah, it is. Yeah.

John Jantsch (01:24.439)

Right.

Neen (01:45.339)

But I think it’s exclusive because we all have the privilege of being able to roll out a red carpet experience for our clients, for our team members. And so if you look at my body of work, you mentioned intentionality and attention. So if you think back through the books that I’ve already written, folding time, I said to the world, you can’t manage time, but you can manage your attention. And then I published Attention Pays, where I said it’s really intention that makes our attention valuable.

And I had shared that attention’s about connection, right? And I see my new book, Exceptional Experiences, as the evolution of all of those things, because what I believe is that it’s really luxury is about the human connection, and now more than ever before in our digital AI world, John, I think we’re all craving that human connection. So really to me, luxury, what it means to me and what it means to you could be different. And so what I did was a research study on that.

very topic. So even luxury as a word, John, it is one that we all need to kind of think about what it means to us personally and what it means to brands.

John Jantsch (02:43.382)

Yeah.

John Jantsch (02:52.174)

Yeah, and I think a lot of people jump immediately to, you know, gold plating or something. mean, you know, like the tangible things, right, of luxury. And I think I may have read this actually in your work. It’s really more, luxury is more of a feeling or how you make somebody feel, right? Or how whatever the product or purchasing the product makes you feel. And I think that that’s probably the, I mean, should we even say luxurious? Does that sound more like a feeling?

Neen (02:56.951)

Sure. Mm-hmm.

in your work. It’s really more…

Neen (03:07.803)

Right. Yes.

Neen (03:16.635)

Should we even say luxurious? that sound more like a feeling? Yeah, and I think it is. But John, think too what makes you feel special and feels like luxurious to you could be different to someone else. But we all have this power. have this power to create these experiences for others, which is why the book has been called exceptional experiences, because I think one of the things that I did when I did this proprietary research study, the only one of its kind in the world.

John Jantsch (03:29.678)

I assure you it is. I assure you it is.

Neen (03:47.131)

While people have different versions of what luxury is, they have different mindsets, What they all agreed was that luxury could be defined as high quality, long lasting, unique, authentic and indulgent. Now, indulgent is the word that most people will be like, you know, some people are like, I don’t know if that’s me, but think about all the other four words, John. They could apply to leadership.

John Jantsch (03:53.55)

Mm-hmm.

Neen (04:14.863)

High quality, long lasting, authentic and unique. And so that’s truly how luxury is defined. So then what we do is we take it a step further and say, well, what does luxury mean for you? And that could be different.

John Jantsch (04:26.73)

Yeah. So, so also in the subtitle, five luxury levers, attention, anticipation, personalization, generosity, gratitude. Did I get that right?

Neen (04:28.077)

So also at the summer.

Neen (04:36.771)

Yeah, so we have taken these five luxury levers and what we’ve said is because of all the consulting that I do with global brands, whether it’s as a keynote or whether I’m confident to the CEOs working with their teams, what I realized was this experience elevation model, which is the framework is inside the book. You can all see that in the book is what I realized is.

My CEOs are measured on two things. And so are so many of the small businesses listening to this or the marketing professionals. And that is they’re measured on mind share and market share. The model has been designed so that you do everything from capturing the attention of the clients you want to work with, right? Which as marketers, we always were in the attention business, right? How do we capture the attention? And so that is really top of mind. How do you really grab that mind share all the way through to the pinnacle of the model is how do you create

advocates of those same people, which is really about driving revenue, which is about market share. So if you think top of mind, top of market, what my experience elevation model does inside the book, it’s just a framework that anyone can apply as you entice people to do business with you and invite them into your community. You get them excited about what you’re offering and then delight them with all the different ways you can do that. So you ignite them to be advocates. That’s the five luxury levers.

John Jantsch (05:56.654)

All right, so let’s unpack them, each of the words, can we? And you say lever, I say lever, I don’t know.

Neen (06:01.168)

Yeah!

Let’s yeah, we can go with whatever makes you feel comfortable, but I know our listeners are probably saying, what did she say? Lever, lever. We can go with lever for today.

John Jantsch (06:10.318)

Okay, so attention is kind of a loaded word for marketers, know, right? Because it’s getting really noisy. There’s so many distractions because everybody’s trying to get our attention. So what are some practical ways that attention is more about being present rather than being loud?

Neen (06:16.248)

Mm-hmm.

Neen (06:22.046)

So noisy.

Neen (06:32.634)

Mm hmm. It is. I mean, John, think about it as marketers, we’re brilliant storytellers. But what I think we need to do is, and while the book does mention storytelling as a system of elevation, of course, because we need to be able to tell stories. One of the stories that can really capture people’s attention is origin stories.

If you look to luxury brands like Chanel, if you’ve even walked into a Chanel makeup counter in your department store, every product, every piece of merchandise, every name is associated with Coco herself. And as the sales associate explains the name of that lipstick and why it is the way it is and that the merchandise has been designed like the staircase in her apartment in Paris.

All of a sudden as a consumer, you’re like, I need that lipstick because I want to be closer to Chanel. So when it comes to attention, it’s not just about storytelling. It’s also about the origin story so that people get to understand why you as the small business owner, why you as the marketer are so passionate. But another system and a practical thing we talk about here as far as capturing attention, John, is being more collaborative and being very creative. Billy Carl-Samuel, one of my favorite champagne houses.

They partnered with Hansman Seville Rowe, a bespoke suit tailor. Now, what do those two businesses have in common? Well, they share the same kind of clients, but what they were able to do was to create a tweed that was based on champagne. The white flowers, the white foam of champagne, the steel vats with the silver, the green leaves of the vines. And so they created a tweed based on their partnership that they then sold to their clients.

So understanding that if we want to capture attention now, John, we have to do it in more creative ways through the origin stories, through the collaborations we have. But being present for some of us in the most practical sense is sometimes just putting our phone down. Sometimes it’s just actually looking at the person and saying hello and making them feel seen and heard. That’s a very easy way for all of us, no matter what business we’re in, to be more present.

John Jantsch (08:39.624)

I want to go to another one and we don’t have to unpack all five of these, but one that I thought was kind of curious or I’m curious about was anticipation as the hallmark of luxury. Can you maybe use an example of that one? Because the book is loaded with case studies.

Neen (08:54.679)

Yeah, I love this. Yes. When you think about it, the luxury lever, to use your word, of delight is, know, how do we anticipate needs that people don’t even know they have? And let’s think about this. If you, think too often as marketers, as small businesses, as managers of businesses, we act like the bellhop. And a bellhop in a hotel is vital. They move the bags quickly through the hotel lobby and up to your room and efficiency is key and it’s very transactional for them, right?

But if you think about it, we don’t want to think like a bellhop. We want to think like a concierge. Because a concierge, John, they’re the most well-known revered position in a hotel. They’re the go-to person, which is what we want to be as a small business or a marketer, right? And what they do is they get us that ticket to that particular concert or that table. We couldn’t get that reservation, but here’s how a concierge is different. A concierge anticipates needs we didn’t even know we had.

They make suggestions in our community or in the hotel or things we didn’t even know we wanted. But what that requires is a fascination. Luxury brands are genius at personalization and customization. Personalization is really about information and as marketers we have a lot of information data points. Customization is about connection. How do you connect in a deeper way to the clients who already love you or want to do business with you?

But I think it is fascination that requires that anticipation. We have to be so curious about the people we want to serve, John, that we ask the extra questions, that we get to give them our undivided attention. So personalization, customization, fascination, this anticipation, we need to have systems in place to do that. We need to teach our team to be more curious.

to spend more time, to capture those data points so we can use it in our conversations later. It might be the simplicity of a newsletter that you have and actually using the person’s name and capturing their first name in your sign up form so that that’s the simplest, easiest way and get it right so the spelling is correct. But let’s like.

Neen (11:06.337)

simplest form, we love the sound of our own name, John. You know, if you go into your coffee shop and they know your name or your favorite restaurant, you just smile a little bigger because someone saw you. That’s what anticipation is.

John Jantsch (11:25.826)

You know, it’s funny. mean, some of this is right out of, some ways is right out of how to win friends and influence people, right? It’s some of the…

Neen (11:32.883)

Dale Carnegie said it himself in the early 1900s when he wrote that book he says a person’s name is the sweetest sound and he was right back then and it’s as right today as it was back then because but the stealth message don’t tell anyone but the real message of this book John is how do you make people feel seen heard and valued luxury brands do that so so well my whole body of work is about how do you create these moments that matter for people

And he had it right when he wrote that book, How to Win Friends and Influence People. And we all crave that.

John Jantsch (12:13.41)

You talk about something, because I’m sure there’s some people that are starting to say, okay, this is great. Like, how do we start kind of thinking this way or bringing this around? You talk about something you call experience audits. You want to kind of walk us through that?

Neen (12:16.795)

There’s some people that starting to say, okay, this is great. Like how do we start?

something you call experience on it. Can you walk us through that? Yeah.

It doesn’t matter, you don’t have to have a luxury product to provide a luxury level of service, right? So you could be running a mechanic shop. I use the same consulting model when I’m working with the emergency rooms for some of my hospital clients. So you can apply these five luxury levers at any business. It’s really about finding the system of elevation that makes the most sense for you and what you’re trying to achieve. But an easy experience audit is maybe you could even find out what the luxury points are not.

doesn’t feel like luxury in your business if there’s too many forms to fill out, if the lines are too long, if there’s weeds in your garden, if there’s dusty old magazines in your reception area. It’s very easy to see and look around what’s not luxury, John. That’s a really easy starting point. I do encourage businesses, regardless of what type of business you have, to if you want to upskill your team to provide a more luxury level of service,

Send them to a hotel lobby, give them a budget, get them to order a coffee and sit and observe what’s going on. Do they notice the way the staff move, they dress, they speak, the sounds, the smells, the touch points, the service they receive? Allow your team members to enjoy some luxury so they understand it and then get them to come back and debrief it with the team. What did they see, hear, smell, touch?

Neen (13:48.74)

What was all of the senses that were engaged in that experience so they can do an audit out into the world as well? I also really encourage my teams, the clients I work with to mystery shop, to mystery shop, have someone mystery shop their business. Now this is an old technique yet it’s still valid for today, right? Mystery shop your competitors, mystery shop, have someone mystery shop your business and then do a bit of a readout so the team get to hear.

This was their experience. There’s so many ways you can do an experience audit.

John Jantsch (14:21.218)

You know, it’s funny, when I think back in hindsight, some of the best experiences, luxury experiences I’ve had, wasn’t, the place wasn’t trying to be that. They weren’t trying to put that on as like, we’re very, like you said, exclusive. They just did everything. In some ways you don’t notice luxury, right?

Neen (14:26.485)

experiences I’ve had. wasn’t, the place wasn’t.

Neen (14:39.684)

Yes, and it’s easy because one of the things that often is associated with luxury is ease. The Ritz has a, they have a preference that you only ever enter your information once. Now let’s think about this. Like I was at a hotel this week. I mean, I travel for a living. That’s my job. Some people drive, I fly. It’s the same thing.

It’s just different form of commute. So I stay in a lot of hotels and every time I open my computer I had to add my hotel room and my name for the Wi-Fi I mean multiple times think of how often we open and close that computer and so the Ritz has got it right because they’re like Let’s just enter your information once so now the system says I see you. Mr. Jance I’m so glad that you’re back with us and then that’s all you have to do. So sometimes luxury is ease How do we make it really easy for people to do business with us?

John Jantsch (15:08.419)

Yes.

John Jantsch (15:28.012)

Yeah. So, all right. If you were going to, I loved, I love doing this to people that write books and they have like five key things or seven key things. And I asked them to pick the fit, not only their favorite, but like if somebody came to you and they probably do this at the end of a talk, right? Okay. That’s all great, Neen. But like, what’s the one thing I need to focus on like for the next 30 days, what would you tell them?

Neen (15:41.532)

If somebody came to you…

Neen (15:48.419)

Yeah!

can tell you what my favorite thing is that often gets overlooked. And that is how do you really engage the five senses? Because John, we all know this, especially as marketers, that our sense of smell gives us a deeper emotional connection to a brand. We can smell a meal or a fragrance from someone who’s important to us and all of a sudden we’re transported back.

Look at something like the Addition Hotels. They have a signature fragrance. If I walk into the Tampa Addition, the Madrid Addition, or the New York Addition Hotel, every time I know exactly where I am because they have a signature scent. I would invite people that regardless of what business you’re in, how do you engage the five senses? And if you’re a digital business, if everything’s 100 % online, think about how you’re using the language of sight and smell and touch.

And think about how do you elevate that? Look at Ikea. 60 % of the purchases at Ikea are unplanned. Why? Because they deliberately appeal to all five senses. You smell the meatballs, you walk through the store, you touch the fabrics, you build it yourself. And then $500 later that you didn’t even know you needed to spend, you’ve got a whole lot of to-do list items because you’ve been shopping at Ikea. They’re geniuses at this. So I would say to people, start.

with thinking how do we engage the senses in the lobby, the reception, the collaterals, all of those things.

John Jantsch (17:14.83)

I was going to ask you, not just digital businesses, mean, every type of business is using more automation. We’re using AI. We’re becoming more efficient. We’re in some ways distancing the customer. How do you take advantage of the fact that I think people are craving that more because they’re losing it?

Neen (17:17.884)

I mean, every type of business is using more automation. We’re using AI. We’re becoming more efficient.

Neen (17:31.621)

take it.

Neen (17:37.966)

Because I do things like I still write handwritten notes. I’m a big fan of a handwritten note. And so that’s an easy way to say to a client, we really appreciate doing business with you. And it costs me a stamp and two minutes of my time. I’m also a fan of sending like what I call lumpy mail. So like actual packages in the post so that someone opens it. Because if you get your mail at the end of the day, I don’t know about you, but all the white envelopes generally equal some sort of bill or invoice. So if I get something that feels like a present.

John Jantsch (17:41.837)

Yeah.

John Jantsch (17:55.074)

Mm-hmm.

John Jantsch (18:05.878)

or no, it’s a credit card application. It’s what it is. Yeah.

Neen (18:07.708)

It’s awesome. Okay, a credit card. There you go. There you go. So I think what we need to think about is how do we bring the human connection back into those opportunities? How about instead of just sending an email, what if you got out your cell phone and you shot a short video and sent a text message and said, I love doing business with you. By the way, we just got this new set of tires in. I think they’d be great for your car.

John Jantsch (18:23.726)

Mm-hmm.

Neen (18:32.636)

I just wanted to let you know about them. Here’s a picture of them. Send. imagine if we brought our voice, our human voice back into business through video messaging, through the text messaging, through voice notes. There’s so easy ways. It still feels like a system of elevation, but instead of just sending yet another email that’s going to land in someone’s inbox and get cluttered up by the 200 other emails they have, what if you leverage that personal touch?

That’s the type of thing. If you see something and say, Hey, I saw this and I thought of you. That’s a very easy line to say to a customer. Like I see you, I hear you. know you’re important to me. That’s why I think luxury is about human connection.

John Jantsch (19:16.204)

Yeah. And I, and I do think, I mean, I personally recognize when somebody, I mean, it’s easy to hit, like you hit, you said send, you know, to 20,000 people at once, right? That’s why it’s appealing because you can do it. But, but yeah, I was going to say, but I, I, I personally noticed when somebody does something that I know they can’t automate.

Neen (19:25.308)

Right? That’s why it’s appealing. Sure, it’s efficient, but that’s thinking like a bellhop.

I notice when somebody does that.

Yes. And it’s more obvious now, John. And so when you think about it, if you really want people to pay attention to what you’re doing, you don’t want to be like everybody else. You want to think about, for example, I use pink, my brand is pink, if people didn’t know that, and you’re listening to this, I use pink mailers for books that I send out. Does it cost a little more? Sure. But when people get it, they say, I know it was from you immediately.

John Jantsch (19:39.799)

Yeah.

Neen (20:02.33)

because there’s a consistency of the brand, right? But I still have to ship things. So I most will just choose something that feels a little bit more unique. I hand write labels so that they know that it’s my handwriting that I took the time to send it to them. That’s why I like to write a handwritten note that you can’t order. I mean, you can, that’s not true. You can automate that kind of thing now, but I feel like we have to think about, especially those top tier clients that we’re have, that we’re serving.

What is it that we’re doing for them? It could be the simplicity, John, of having a private event. Maybe, let’s say you’re working, going back to the tire shop example, you might be running a tire shop, which does not feel like luxury, but you know what you could do?

You could open a little bit earlier for your top tier clients. They could meet the mechanics. They could explain more about the tires and the wheel balancing and how you take care of them and what to do in bad weather. And all of a sudden you’re getting more of an exclusive luxury experience from your local tire dealer. It doesn’t take a lot of thought, but it does take effort.

John Jantsch (21:06.818)

Yeah, it’s also interesting. mean, you expect a luxury experience from the bespoke tailor. mean, that’s sort of like that’s the bar of entry for them, right? So imagine this business that you’re not really expecting that from. What a differentiator, right?

Neen (21:12.644)

Of course.

Neen (21:21.402)

Yes and then because it’s so differentiated, the client can’t help but tell other people. We used a Tyler for a home project many years ago. I cannot tell you how many times I have referred that Tyler. They had perfectionism like I’ve never seen before. They cleaned up. They were so lovely, so polite, well groomed and

People want that level of service from anyone who’s in their home, but this Tyler, he went above and beyond all of that. And so what I want people to think about is luxury, that connection point. What is it you could do to anticipate things? People didn’t even know they needed, therefore thinking more like a concierge. We can all do that. We just have to invest the time and energy to think about it in advance. Then you can systemize it.

John Jantsch (22:06.336)

And now we’re back to attention, aren’t we? So, Neen, I appreciate you taking a few moments to stop by. Where would you invite people to connect with you? Obviously, find out about your work and your latest book.

Neen (22:08.152)

Always about attention,

Neen (22:19.328)

Neenjames.com you can find out everything there. You can also download a free self assessment to find out what your own luxury mindset is. It’ll take you less than five minutes to do it. It’s free. So go to the website Neenjames.com grab your copy of the book and download the assessment.

John Jantsch (22:33.824)

Awesome. Well, again, I appreciate you taking a moment and hopefully we’ll run into you one of these days out there on the road.

Neen (22:38.864)

I would love that. Thank you for everything you do in the world, John.

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I’ll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

Alien: Earth Finale – In Conversation With The Eyeball’s Newest Host

This article contains spoilers for Alien: Earth episode 8. There’s a long-standing tradition in storytelling: If you introduce a parasitic alien eyeball in the first act, it had better take over someone’s brain by the third act. While it certainly made for a stunning, downright demonic visual, the so-called “eye midge” of FX’s Alien: Earth […]

The post Alien: Earth Finale – In Conversation With The Eyeball’s Newest Host appeared first on Den of Geek.

This article contains spoilers for Alien: Earth episode 8.

There’s a long-standing tradition in storytelling: If you introduce a parasitic alien eyeball in the first act, it had better take over someone’s brain by the third act.

While it certainly made for a stunning, downright demonic visual, the so-called “eye midge” of FX’s Alien: Earth couldn’t occupy the orbital socket of that sheep all season. At a certain point, the little buddy known as T. Ocellus would have to find a human host like it did aboard the USCSS Maginot when it commandeered the engineer Shmuel (Michael Smiley). Fan theories regarding the eyeball’s next host ran the gamut from the obvious (Samuel Blenkin’s Boy Kavalier) to the unlikely (any of the hybrids) to the wickedly creative (the xenomorph herself).

cnx({

playerId: “106e33c0-3911-473c-b599-b1426db57530”,

}).render(“0270c398a82f44f49c23c16122516796”);

});

In the end, however, the eye-opening moment doesn’t belong to any of those candidates but rather humble egghead Arthur Sylvia… or, more accurately: what’s left of Arthur Sylvia. Near the conclusion of the Alien: Earth season 1 finale “The Real Monsters,” the action cuts away from the claustrophobic confines of Prodigy Corporation’s Neverland compound to the sunny Thai beach outside. There Arthur’s corpse has washed ashore, with the fatherly scientist having been killed in the previous episode by the a more familiar Alien foe: the chestburster. The loose T. Ocellus skitters across the sand, removes Arthur’s moldering left eye, and crawls in. Arthur’s body jolts up, now host to its second extraterrestrial invader in as many days.

“I’ve been thinking a lot about the fact that I’ve never played an alien before,” Arthur Syliva actor David Rysdahl says. “There’s such an absurdity to this T. Ocellus that I think it’d be really fun to play.”

Rysdahl is one of several Alien: Earth performers who have previously worked with series showrunner Noah Hawley in his FX anthology effort Fargo. Den of Geek caught up with the affable Midwest-born actor to discuss how that Hawley connection led to Arthur’s big moment and what he hopes to see through that cursed eye in Alien: Earth season 2.

Den of Geek: What was your reaction when you heard that the Eyeball would be going into your head?

David Rysdahl: The Eyeball was a last minute thing. It was the night before the episode eight scripts came in and Noah texted me ‘I’m not done with you yet.” I thought I was gonna be done for the season! It was a moment of discovery for both Arthur and for David.

Have you been following the online chatter for Alien: Earth at all? “Whose brain is the Eyeball ending up in?” has been a hot topic of conversation.

A little bit. I try to dabble in it. I do find it interesting – you make something and then it’s not yours anymore. It’s the world’s, it’s everybody’s, it’s all of ours now. I had seen some of the speculation of like “who’s it going to go into?” [The cast and crew] all actually thought similarly to the fans when we were shooting it. We were like “it’s gonna go into somebody in episode eight.” Little did we know it would be Arthur’s corpse. We actually had a very similar and parallel experience to what the fans are having now.

Has Noah let you in on what’s in store for Arthur in season 2 at all? What are you hoping for?

We’re still figuring it out. Noah’s got a lot of ideas but he’s always a little tight-lipped. I’ve been thinking a lot about the fact that I’ve never played an alien before. I’ve never played something that’s seen a lot of the universe but also has a sense of humor. Like the pi episode with the shit on the floor. That’s funny! There’s such an absurdity to this T. Ocellus that I think it’d be really fun to play. I mean, there are already a lot of rules for this little creature from season one. What does it do to the brain that it’s in? It uses this new lens to see the world, and Arthur’s a new lens so how much of Arthur can I bring in? I’m having a lot of ideas as an actor already, so we’ll see how Noah wants to shape it.

Your one scene in the finale obviously packs a punch but I feel like the penultimate episode is Arthur’s finest hour. What was it like playing that scene with Slightly (Adarsh Gourav) and Smee (Jonathan Ajayi) in which you’re very gentle with them, holding their hands and teaching them about lying, just before the chestburster moment?

Noah and I talked about this idea that I’m a scientist and I’m a dad. And slowly through the course of the season, the dad wins out. That last scene needs to feel “full father.” I’m no longer seeing them as hybrids; I’m seeing them as two children who I care for deeply.

We’ve all seen what the chestburster does. So the “what” is not in question, but the “how” is interesting. We were like “well, what makes this chestburster moment distinct and interesting from the ones that have come before us?” This is a father being chestbursted by his “son” to birth a new “xenomorph son” in a way. It was actually the simplest scene because all the science has faded, and it’s just me being a father to two troubled sons.

From a physical acting perspective, what is it like to be chestbursted? Did you do research into previous chestburstings?

Definitely. You know that you’re entering canon so you have to pay respect to what’s come before you and then also try to do it your own way. I watched John Hurt in that original chestburster scene a lot. We shot the exterior beach scene, and then we showed the actual chestbursting on a platform made of sand, where half of my body is not mine. It’s a puppet being worked on with three puppeteers. The “burster” itself is its own puppet and it’s all mechanical.

The moment is not just mine. It’s this group of people who’ve come together who have researched it and practiced it every couple of weeks. You just kind of trust that whatever’s happening feels correct and unique. You don’t have to imagine too much because it’s actually happening to you in that moment. That’s kind of what I love about being an actor. When else would you be able to go through something like that? Well, hopefully never, but I crave that experience as a person. And acting allows you to have these experiences that are literally extraterrestrial.

As one of the few performers who Noah brought over to Alien: Earth from Fargo, what was it like working with him on this versus that original experience?

For myself, [Fargo season 5 character] Wayne and Arthur are kind of mirror images. They’re two fathers who go through crises with their families. Wayne is so optimistic that he’s never going to be hurt, right? Arthur has so many conflicting emotions and this sense that he’s doomed. And then you have the contrast of a very cold place [of Fargo‘s Minnesota] and a very hot place [of Alien: Earth‘s Thailand]. Fargo is musical and melodious in its language. Alien is very ’70s with the naturalism of this heightened science fiction.

They’re still Noah Hawley’s magic and he is still paying tribute to the source material and then wanting you to make a choice. Noah’s always like “just make a choice. I’ll tell you if it’s right or not. Just make a strong choice.” It’s a collaboration because he’ll then be able to write for you as you go forward. He sees things happening in the beginning of the season that he wants to amplify or change course on throughout. They’re two different beats but it’s still Noah Hawley’s brilliant brain.

Is there anything else you want to mention about your Alien: Earth experience that you haven’t gotten the chance to say yet?

I think I haven’t talked enough about how Thailand is a character in the show – the people, the landscape – it’s a really special culture. Just being in that allows for new ideas and new perspectives to infiltrate your actor body. Talking about Alien with a crew that doesn’t speak English: it’s a story about people and I think that’s important right now. Being taken care of by these amazing Thai people and even being invited out to play pickleball or whatever on weekends really helped me feel like this is a global show. And I think that’s translated into the work.

All eight episodes of Alien: Earth are available to stream on Hulu now.

The post Alien: Earth Finale – In Conversation With The Eyeball’s Newest Host appeared first on Den of Geek.

Is Peacemaker Season 2 About to Adapt the Darkest DC Universe?

This post contains spoilers for Peacemaker season 2 episodes 1-5. For the first five episodes of Peacemaker‘s second season, Chris Smith believes that he has found the best universe ever. This alternate reality that he accesses through a Quantum Folding Chamber offers everything that Chris wants. Not only is his father kind and supportive, not […]

The post Is Peacemaker Season 2 About to Adapt the Darkest DC Universe? appeared first on Den of Geek.

This article contains spoilers for Alien: Earth episode 8.

There’s a long-standing tradition in storytelling: If you introduce a parasitic alien eyeball in the first act, it had better take over someone’s brain by the third act.

While it certainly made for a stunning, downright demonic visual, the so-called “eye midge” of FX’s Alien: Earth couldn’t occupy the orbital socket of that sheep all season. At a certain point, the little buddy known as T. Ocellus would have to find a human host like it did aboard the USCSS Maginot when it commandeered the engineer Shmuel (Michael Smiley). Fan theories regarding the eyeball’s next host ran the gamut from the obvious (Samuel Blenkin’s Boy Kavalier) to the unlikely (any of the hybrids) to the wickedly creative (the xenomorph herself).

cnx({

playerId: “106e33c0-3911-473c-b599-b1426db57530”,

}).render(“0270c398a82f44f49c23c16122516796”);

});

In the end, however, the eye-opening moment doesn’t belong to any of those candidates but rather humble egghead Arthur Sylvia… or, more accurately: what’s left of Arthur Sylvia. Near the conclusion of the Alien: Earth season 1 finale “The Real Monsters,” the action cuts away from the claustrophobic confines of Prodigy Corporation’s Neverland compound to the sunny Thai beach outside. There Arthur’s corpse has washed ashore, with the fatherly scientist having been killed in the previous episode by the a more familiar Alien foe: the chestburster. The loose T. Ocellus skitters across the sand, removes Arthur’s moldering left eye, and crawls in. Arthur’s body jolts up, now host to its second extraterrestrial invader in as many days.

“I’ve been thinking a lot about the fact that I’ve never played an alien before,” Arthur Syliva actor David Rysdahl says. “There’s such an absurdity to this T. Ocellus that I think it’d be really fun to play.”

Rysdahl is one of several Alien: Earth performers who have previously worked with series showrunner Noah Hawley in his FX anthology effort Fargo. Den of Geek caught up with the affable Midwest-born actor to discuss how that Hawley connection led to Arthur’s big moment and what he hopes to see through that cursed eye in Alien: Earth season 2.

Den of Geek: What was your reaction when you heard that the Eyeball would be going into your head?

David Rysdahl: The Eyeball was a last minute thing. It was the night before the episode eight scripts came in and Noah texted me ‘I’m not done with you yet.” I thought I was gonna be done for the season! It was a moment of discovery for both Arthur and for David.

Have you been following the online chatter for Alien: Earth at all? “Whose brain is the Eyeball ending up in?” has been a hot topic of conversation.

A little bit. I try to dabble in it. I do find it interesting – you make something and then it’s not yours anymore. It’s the world’s, it’s everybody’s, it’s all of ours now. I had seen some of the speculation of like “who’s it going to go into?” [The cast and crew] all actually thought similarly to the fans when we were shooting it. We were like “it’s gonna go into somebody in episode eight.” Little did we know it would be Arthur’s corpse. We actually had a very similar and parallel experience to what the fans are having now.

Has Noah let you in on what’s in store for Arthur in season 2 at all? What are you hoping for?

We’re still figuring it out. Noah’s got a lot of ideas but he’s always a little tight-lipped. I’ve been thinking a lot about the fact that I’ve never played an alien before. I’ve never played something that’s seen a lot of the universe but also has a sense of humor. Like the pi episode with the shit on the floor. That’s funny! There’s such an absurdity to this T. Ocellus that I think it’d be really fun to play. I mean, there are already a lot of rules for this little creature from season one. What does it do to the brain that it’s in? It uses this new lens to see the world, and Arthur’s a new lens so how much of Arthur can I bring in? I’m having a lot of ideas as an actor already, so we’ll see how Noah wants to shape it.

Your one scene in the finale obviously packs a punch but I feel like the penultimate episode is Arthur’s finest hour. What was it like playing that scene with Slightly (Adarsh Gourav) and Smee (Jonathan Ajayi) in which you’re very gentle with them, holding their hands and teaching them about lying, just before the chestburster moment?

Noah and I talked about this idea that I’m a scientist and I’m a dad. And slowly through the course of the season, the dad wins out. That last scene needs to feel “full father.” I’m no longer seeing them as hybrids; I’m seeing them as two children who I care for deeply.

We’ve all seen what the chestburster does. So the “what” is not in question, but the “how” is interesting. We were like “well, what makes this chestburster moment distinct and interesting from the ones that have come before us?” This is a father being chestbursted by his “son” to birth a new “xenomorph son” in a way. It was actually the simplest scene because all the science has faded, and it’s just me being a father to two troubled sons.

From a physical acting perspective, what is it like to be chestbursted? Did you do research into previous chestburstings?

Definitely. You know that you’re entering canon so you have to pay respect to what’s come before you and then also try to do it your own way. I watched John Hurt in that original chestburster scene a lot. We shot the exterior beach scene, and then we showed the actual chestbursting on a platform made of sand, where half of my body is not mine. It’s a puppet being worked on with three puppeteers. The “burster” itself is its own puppet and it’s all mechanical.

The moment is not just mine. It’s this group of people who’ve come together who have researched it and practiced it every couple of weeks. You just kind of trust that whatever’s happening feels correct and unique. You don’t have to imagine too much because it’s actually happening to you in that moment. That’s kind of what I love about being an actor. When else would you be able to go through something like that? Well, hopefully never, but I crave that experience as a person. And acting allows you to have these experiences that are literally extraterrestrial.

As one of the few performers who Noah brought over to Alien: Earth from Fargo, what was it like working with him on this versus that original experience?

For myself, [Fargo season 5 character] Wayne and Arthur are kind of mirror images. They’re two fathers who go through crises with their families. Wayne is so optimistic that he’s never going to be hurt, right? Arthur has so many conflicting emotions and this sense that he’s doomed. And then you have the contrast of a very cold place [of Fargo‘s Minnesota] and a very hot place [of Alien: Earth‘s Thailand]. Fargo is musical and melodious in its language. Alien is very ’70s with the naturalism of this heightened science fiction.

They’re still Noah Hawley’s magic and he is still paying tribute to the source material and then wanting you to make a choice. Noah’s always like “just make a choice. I’ll tell you if it’s right or not. Just make a strong choice.” It’s a collaboration because he’ll then be able to write for you as you go forward. He sees things happening in the beginning of the season that he wants to amplify or change course on throughout. They’re two different beats but it’s still Noah Hawley’s brilliant brain.

Is there anything else you want to mention about your Alien: Earth experience that you haven’t gotten the chance to say yet?

I think I haven’t talked enough about how Thailand is a character in the show – the people, the landscape – it’s a really special culture. Just being in that allows for new ideas and new perspectives to infiltrate your actor body. Talking about Alien with a crew that doesn’t speak English: it’s a story about people and I think that’s important right now. Being taken care of by these amazing Thai people and even being invited out to play pickleball or whatever on weekends really helped me feel like this is a global show. And I think that’s translated into the work.

All eight episodes of Alien: Earth are available to stream on Hulu now.

The post Alien: Earth Finale – In Conversation With The Eyeball’s Newest Host appeared first on Den of Geek.

Live Auction Brings The Fantastic Four and Other Marvel Comics to Collectors Everywhere

Comic fans and collectors are in for a treat this week as eBay Live plays host to an exclusive auction featuring some of Marvel’s rarest treasures. The live event will take place Thursday, September 25, 2025, at 7 p.m. ET and will be led by a trio of familiar faces for our regular attendees: legendary […]

The post Live Auction Brings The Fantastic Four and Other Marvel Comics to Collectors Everywhere appeared first on Den of Geek.

This article contains spoilers for Alien: Earth episode 8.

There’s a long-standing tradition in storytelling: If you introduce a parasitic alien eyeball in the first act, it had better take over someone’s brain by the third act.

While it certainly made for a stunning, downright demonic visual, the so-called “eye midge” of FX’s Alien: Earth couldn’t occupy the orbital socket of that sheep all season. At a certain point, the little buddy known as T. Ocellus would have to find a human host like it did aboard the USCSS Maginot when it commandeered the engineer Shmuel (Michael Smiley). Fan theories regarding the eyeball’s next host ran the gamut from the obvious (Samuel Blenkin’s Boy Kavalier) to the unlikely (any of the hybrids) to the wickedly creative (the xenomorph herself).

cnx({

playerId: “106e33c0-3911-473c-b599-b1426db57530”,

}).render(“0270c398a82f44f49c23c16122516796”);

});

In the end, however, the eye-opening moment doesn’t belong to any of those candidates but rather humble egghead Arthur Sylvia… or, more accurately: what’s left of Arthur Sylvia. Near the conclusion of the Alien: Earth season 1 finale “The Real Monsters,” the action cuts away from the claustrophobic confines of Prodigy Corporation’s Neverland compound to the sunny Thai beach outside. There Arthur’s corpse has washed ashore, with the fatherly scientist having been killed in the previous episode by the a more familiar Alien foe: the chestburster. The loose T. Ocellus skitters across the sand, removes Arthur’s moldering left eye, and crawls in. Arthur’s body jolts up, now host to its second extraterrestrial invader in as many days.

“I’ve been thinking a lot about the fact that I’ve never played an alien before,” Arthur Syliva actor David Rysdahl says. “There’s such an absurdity to this T. Ocellus that I think it’d be really fun to play.”

Rysdahl is one of several Alien: Earth performers who have previously worked with series showrunner Noah Hawley in his FX anthology effort Fargo. Den of Geek caught up with the affable Midwest-born actor to discuss how that Hawley connection led to Arthur’s big moment and what he hopes to see through that cursed eye in Alien: Earth season 2.

Den of Geek: What was your reaction when you heard that the Eyeball would be going into your head?

David Rysdahl: The Eyeball was a last minute thing. It was the night before the episode eight scripts came in and Noah texted me ‘I’m not done with you yet.” I thought I was gonna be done for the season! It was a moment of discovery for both Arthur and for David.

Have you been following the online chatter for Alien: Earth at all? “Whose brain is the Eyeball ending up in?” has been a hot topic of conversation.

A little bit. I try to dabble in it. I do find it interesting – you make something and then it’s not yours anymore. It’s the world’s, it’s everybody’s, it’s all of ours now. I had seen some of the speculation of like “who’s it going to go into?” [The cast and crew] all actually thought similarly to the fans when we were shooting it. We were like “it’s gonna go into somebody in episode eight.” Little did we know it would be Arthur’s corpse. We actually had a very similar and parallel experience to what the fans are having now.

Has Noah let you in on what’s in store for Arthur in season 2 at all? What are you hoping for?

We’re still figuring it out. Noah’s got a lot of ideas but he’s always a little tight-lipped. I’ve been thinking a lot about the fact that I’ve never played an alien before. I’ve never played something that’s seen a lot of the universe but also has a sense of humor. Like the pi episode with the shit on the floor. That’s funny! There’s such an absurdity to this T. Ocellus that I think it’d be really fun to play. I mean, there are already a lot of rules for this little creature from season one. What does it do to the brain that it’s in? It uses this new lens to see the world, and Arthur’s a new lens so how much of Arthur can I bring in? I’m having a lot of ideas as an actor already, so we’ll see how Noah wants to shape it.

Your one scene in the finale obviously packs a punch but I feel like the penultimate episode is Arthur’s finest hour. What was it like playing that scene with Slightly (Adarsh Gourav) and Smee (Jonathan Ajayi) in which you’re very gentle with them, holding their hands and teaching them about lying, just before the chestburster moment?

Noah and I talked about this idea that I’m a scientist and I’m a dad. And slowly through the course of the season, the dad wins out. That last scene needs to feel “full father.” I’m no longer seeing them as hybrids; I’m seeing them as two children who I care for deeply.

We’ve all seen what the chestburster does. So the “what” is not in question, but the “how” is interesting. We were like “well, what makes this chestburster moment distinct and interesting from the ones that have come before us?” This is a father being chestbursted by his “son” to birth a new “xenomorph son” in a way. It was actually the simplest scene because all the science has faded, and it’s just me being a father to two troubled sons.

From a physical acting perspective, what is it like to be chestbursted? Did you do research into previous chestburstings?

Definitely. You know that you’re entering canon so you have to pay respect to what’s come before you and then also try to do it your own way. I watched John Hurt in that original chestburster scene a lot. We shot the exterior beach scene, and then we showed the actual chestbursting on a platform made of sand, where half of my body is not mine. It’s a puppet being worked on with three puppeteers. The “burster” itself is its own puppet and it’s all mechanical.

The moment is not just mine. It’s this group of people who’ve come together who have researched it and practiced it every couple of weeks. You just kind of trust that whatever’s happening feels correct and unique. You don’t have to imagine too much because it’s actually happening to you in that moment. That’s kind of what I love about being an actor. When else would you be able to go through something like that? Well, hopefully never, but I crave that experience as a person. And acting allows you to have these experiences that are literally extraterrestrial.

As one of the few performers who Noah brought over to Alien: Earth from Fargo, what was it like working with him on this versus that original experience?

For myself, [Fargo season 5 character] Wayne and Arthur are kind of mirror images. They’re two fathers who go through crises with their families. Wayne is so optimistic that he’s never going to be hurt, right? Arthur has so many conflicting emotions and this sense that he’s doomed. And then you have the contrast of a very cold place [of Fargo‘s Minnesota] and a very hot place [of Alien: Earth‘s Thailand]. Fargo is musical and melodious in its language. Alien is very ’70s with the naturalism of this heightened science fiction.

They’re still Noah Hawley’s magic and he is still paying tribute to the source material and then wanting you to make a choice. Noah’s always like “just make a choice. I’ll tell you if it’s right or not. Just make a strong choice.” It’s a collaboration because he’ll then be able to write for you as you go forward. He sees things happening in the beginning of the season that he wants to amplify or change course on throughout. They’re two different beats but it’s still Noah Hawley’s brilliant brain.

Is there anything else you want to mention about your Alien: Earth experience that you haven’t gotten the chance to say yet?

I think I haven’t talked enough about how Thailand is a character in the show – the people, the landscape – it’s a really special culture. Just being in that allows for new ideas and new perspectives to infiltrate your actor body. Talking about Alien with a crew that doesn’t speak English: it’s a story about people and I think that’s important right now. Being taken care of by these amazing Thai people and even being invited out to play pickleball or whatever on weekends really helped me feel like this is a global show. And I think that’s translated into the work.

All eight episodes of Alien: Earth are available to stream on Hulu now.

The post Alien: Earth Finale – In Conversation With The Eyeball’s Newest Host appeared first on Den of Geek.

How Alien: Earth Season 2 Can Follow in Aliens’ Footsteps

This article contains spoilers for Alien: Earth episode 8. The true horrors of Neverland have finally been unleashed, and in the Alien: Earth finale, showrunner Noah Hawley ensures the episode lives up to its namesake of “The Real Monsters”. While Wendy (Sydney Chandler) and the rest of the Lost Boys realized their adult carers were […]

The post How Alien: Earth Season 2 Can Follow in Aliens’ Footsteps appeared first on Den of Geek.

This article contains spoilers for Alien: Earth episode 8.

There’s a long-standing tradition in storytelling: If you introduce a parasitic alien eyeball in the first act, it had better take over someone’s brain by the third act.

While it certainly made for a stunning, downright demonic visual, the so-called “eye midge” of FX’s Alien: Earth couldn’t occupy the orbital socket of that sheep all season. At a certain point, the little buddy known as T. Ocellus would have to find a human host like it did aboard the USCSS Maginot when it commandeered the engineer Shmuel (Michael Smiley). Fan theories regarding the eyeball’s next host ran the gamut from the obvious (Samuel Blenkin’s Boy Kavalier) to the unlikely (any of the hybrids) to the wickedly creative (the xenomorph herself).

cnx({

playerId: “106e33c0-3911-473c-b599-b1426db57530”,

}).render(“0270c398a82f44f49c23c16122516796”);

});

In the end, however, the eye-opening moment doesn’t belong to any of those candidates but rather humble egghead Arthur Sylvia… or, more accurately: what’s left of Arthur Sylvia. Near the conclusion of the Alien: Earth season 1 finale “The Real Monsters,” the action cuts away from the claustrophobic confines of Prodigy Corporation’s Neverland compound to the sunny Thai beach outside. There Arthur’s corpse has washed ashore, with the fatherly scientist having been killed in the previous episode by the a more familiar Alien foe: the chestburster. The loose T. Ocellus skitters across the sand, removes Arthur’s moldering left eye, and crawls in. Arthur’s body jolts up, now host to its second extraterrestrial invader in as many days.

“I’ve been thinking a lot about the fact that I’ve never played an alien before,” Arthur Syliva actor David Rysdahl says. “There’s such an absurdity to this T. Ocellus that I think it’d be really fun to play.”

Rysdahl is one of several Alien: Earth performers who have previously worked with series showrunner Noah Hawley in his FX anthology effort Fargo. Den of Geek caught up with the affable Midwest-born actor to discuss how that Hawley connection led to Arthur’s big moment and what he hopes to see through that cursed eye in Alien: Earth season 2.

Den of Geek: What was your reaction when you heard that the Eyeball would be going into your head?

David Rysdahl: The Eyeball was a last minute thing. It was the night before the episode eight scripts came in and Noah texted me ‘I’m not done with you yet.” I thought I was gonna be done for the season! It was a moment of discovery for both Arthur and for David.

Have you been following the online chatter for Alien: Earth at all? “Whose brain is the Eyeball ending up in?” has been a hot topic of conversation.

A little bit. I try to dabble in it. I do find it interesting – you make something and then it’s not yours anymore. It’s the world’s, it’s everybody’s, it’s all of ours now. I had seen some of the speculation of like “who’s it going to go into?” [The cast and crew] all actually thought similarly to the fans when we were shooting it. We were like “it’s gonna go into somebody in episode eight.” Little did we know it would be Arthur’s corpse. We actually had a very similar and parallel experience to what the fans are having now.

Has Noah let you in on what’s in store for Arthur in season 2 at all? What are you hoping for?

We’re still figuring it out. Noah’s got a lot of ideas but he’s always a little tight-lipped. I’ve been thinking a lot about the fact that I’ve never played an alien before. I’ve never played something that’s seen a lot of the universe but also has a sense of humor. Like the pi episode with the shit on the floor. That’s funny! There’s such an absurdity to this T. Ocellus that I think it’d be really fun to play. I mean, there are already a lot of rules for this little creature from season one. What does it do to the brain that it’s in? It uses this new lens to see the world, and Arthur’s a new lens so how much of Arthur can I bring in? I’m having a lot of ideas as an actor already, so we’ll see how Noah wants to shape it.

Your one scene in the finale obviously packs a punch but I feel like the penultimate episode is Arthur’s finest hour. What was it like playing that scene with Slightly (Adarsh Gourav) and Smee (Jonathan Ajayi) in which you’re very gentle with them, holding their hands and teaching them about lying, just before the chestburster moment?

Noah and I talked about this idea that I’m a scientist and I’m a dad. And slowly through the course of the season, the dad wins out. That last scene needs to feel “full father.” I’m no longer seeing them as hybrids; I’m seeing them as two children who I care for deeply.

We’ve all seen what the chestburster does. So the “what” is not in question, but the “how” is interesting. We were like “well, what makes this chestburster moment distinct and interesting from the ones that have come before us?” This is a father being chestbursted by his “son” to birth a new “xenomorph son” in a way. It was actually the simplest scene because all the science has faded, and it’s just me being a father to two troubled sons.

From a physical acting perspective, what is it like to be chestbursted? Did you do research into previous chestburstings?

Definitely. You know that you’re entering canon so you have to pay respect to what’s come before you and then also try to do it your own way. I watched John Hurt in that original chestburster scene a lot. We shot the exterior beach scene, and then we showed the actual chestbursting on a platform made of sand, where half of my body is not mine. It’s a puppet being worked on with three puppeteers. The “burster” itself is its own puppet and it’s all mechanical.

The moment is not just mine. It’s this group of people who’ve come together who have researched it and practiced it every couple of weeks. You just kind of trust that whatever’s happening feels correct and unique. You don’t have to imagine too much because it’s actually happening to you in that moment. That’s kind of what I love about being an actor. When else would you be able to go through something like that? Well, hopefully never, but I crave that experience as a person. And acting allows you to have these experiences that are literally extraterrestrial.

As one of the few performers who Noah brought over to Alien: Earth from Fargo, what was it like working with him on this versus that original experience?

For myself, [Fargo season 5 character] Wayne and Arthur are kind of mirror images. They’re two fathers who go through crises with their families. Wayne is so optimistic that he’s never going to be hurt, right? Arthur has so many conflicting emotions and this sense that he’s doomed. And then you have the contrast of a very cold place [of Fargo‘s Minnesota] and a very hot place [of Alien: Earth‘s Thailand]. Fargo is musical and melodious in its language. Alien is very ’70s with the naturalism of this heightened science fiction.

They’re still Noah Hawley’s magic and he is still paying tribute to the source material and then wanting you to make a choice. Noah’s always like “just make a choice. I’ll tell you if it’s right or not. Just make a strong choice.” It’s a collaboration because he’ll then be able to write for you as you go forward. He sees things happening in the beginning of the season that he wants to amplify or change course on throughout. They’re two different beats but it’s still Noah Hawley’s brilliant brain.

Is there anything else you want to mention about your Alien: Earth experience that you haven’t gotten the chance to say yet?

I think I haven’t talked enough about how Thailand is a character in the show – the people, the landscape – it’s a really special culture. Just being in that allows for new ideas and new perspectives to infiltrate your actor body. Talking about Alien with a crew that doesn’t speak English: it’s a story about people and I think that’s important right now. Being taken care of by these amazing Thai people and even being invited out to play pickleball or whatever on weekends really helped me feel like this is a global show. And I think that’s translated into the work.

All eight episodes of Alien: Earth are available to stream on Hulu now.

The post Alien: Earth Finale – In Conversation With The Eyeball’s Newest Host appeared first on Den of Geek.

Asynchronous Design Critique: Giving Feedback

Feedback, in whichever form it takes, and whatever it may be called, is one of the most effective soft skills that we have at our disposal to collaboratively get our designs to a better place while growing our own skills and perspectives.

Feedback is also one of the most underestimated tools, and often by assuming that we’re already good at it, we settle, forgetting that it’s a skill that can be trained, grown, and improved. Poor feedback can create confusion in projects, bring down morale, and affect trust and team collaboration over the long term. Quality feedback can be a transformative force.

Practicing our skills is surely a good way to improve, but the learning gets even faster when it’s paired with a good foundation that channels and focuses the practice. What are some foundational aspects of giving good feedback? And how can feedback be adjusted for remote and distributed work environments?

On the web, we can identify a long tradition of asynchronous feedback: from the early days of open source, code was shared and discussed on mailing lists. Today, developers engage on pull requests, designers comment in their favorite design tools, project managers and scrum masters exchange ideas on tickets, and so on.

Design critique is often the name used for a type of feedback that’s provided to make our work better, collaboratively. So it shares a lot of the principles with feedback in general, but it also has some differences.

The content

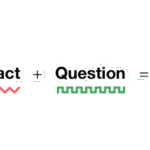

The foundation of every good critique is the feedback’s content, so that’s where we need to start. There are many models that you can use to shape your content. The one that I personally like best—because it’s clear and actionable—is this one from Lara Hogan.

While this equation is generally used to give feedback to people, it also fits really well in a design critique because it ultimately answers some of the core questions that we work on: What? Where? Why? How? Imagine that you’re giving some feedback about some design work that spans multiple screens, like an onboarding flow: there are some pages shown, a flow blueprint, and an outline of the decisions made. You spot something that could be improved. If you keep the three elements of the equation in mind, you’ll have a mental model that can help you be more precise and effective.

Here is a comment that could be given as a part of some feedback, and it might look reasonable at a first glance: it seems to superficially fulfill the elements in the equation. But does it?

Not sure about the buttons’ styles and hierarchy—it feels off. Can you change them?

Observation for design feedback doesn’t just mean pointing out which part of the interface your feedback refers to, but it also refers to offering a perspective that’s as specific as possible. Are you providing the user’s perspective? Your expert perspective? A business perspective? The project manager’s perspective? A first-time user’s perspective?

When I see these two buttons, I expect one to go forward and one to go back.

Impact is about the why. Just pointing out a UI element might sometimes be enough if the issue may be obvious, but more often than not, you should add an explanation of what you’re pointing out.

When I see these two buttons, I expect one to go forward and one to go back. But this is the only screen where this happens, as before we just used a single button and an “×” to close. This seems to be breaking the consistency in the flow.

The question approach is meant to provide open guidance by eliciting the critical thinking in the designer receiving the feedback. Notably, in Lara’s equation she provides a second approach: request, which instead provides guidance toward a specific solution. While that’s a viable option for feedback in general, for design critiques, in my experience, defaulting to the question approach usually reaches the best solutions because designers are generally more comfortable in being given an open space to explore.

The difference between the two can be exemplified with, for the question approach:

When I see these two buttons, I expect one to go forward and one to go back. But this is the only screen where this happens, as before we just used a single button and an “×” to close. This seems to be breaking the consistency in the flow. Would it make sense to unify them?

Or, for the request approach:

When I see these two buttons, I expect one to go forward and one to go back. But this is the only screen where this happens, as before we just used a single button and an “×” to close. This seems to be breaking the consistency in the flow. Let’s make sure that all screens have the same pair of forward and back buttons.

At this point in some situations, it might be useful to integrate with an extra why: why you consider the given suggestion to be better.

When I see these two buttons, I expect one to go forward and one to go back. But this is the only screen where this happens, as before we just used a single button and an “×” to close. This seems to be breaking the consistency in the flow. Let’s make sure that all screens have the same two forward and back buttons so that users don’t get confused.

Choosing the question approach or the request approach can also at times be a matter of personal preference. A while ago, I was putting a lot of effort into improving my feedback: I did rounds of anonymous feedback, and I reviewed feedback with other people. After a few rounds of this work and a year later, I got a positive response: my feedback came across as effective and grounded. Until I changed teams. To my shock, my next round of feedback from one specific person wasn’t that great. The reason is that I had previously tried not to be prescriptive in my advice—because the people who I was previously working with preferred the open-ended question format over the request style of suggestions. But now in this other team, there was one person who instead preferred specific guidance. So I adapted my feedback for them to include requests.

One comment that I heard come up a few times is that this kind of feedback is quite long, and it doesn’t seem very efficient. No… but also yes. Let’s explore both sides.

No, this style of feedback is actually efficient because the length here is a byproduct of clarity, and spending time giving this kind of feedback can provide exactly enough information for a good fix. Also if we zoom out, it can reduce future back-and-forth conversations and misunderstandings, improving the overall efficiency and effectiveness of collaboration beyond the single comment. Imagine that in the example above the feedback were instead just, “Let’s make sure that all screens have the same two forward and back buttons.” The designer receiving this feedback wouldn’t have much to go by, so they might just apply the change. In later iterations, the interface might change or they might introduce new features—and maybe that change might not make sense anymore. Without the why, the designer might imagine that the change is about consistency… but what if it wasn’t? So there could now be an underlying concern that changing the buttons would be perceived as a regression.

Yes, this style of feedback is not always efficient because the points in some comments don’t always need to be exhaustive, sometimes because certain changes may be obvious (“The font used doesn’t follow our guidelines”) and sometimes because the team may have a lot of internal knowledge such that some of the whys may be implied.

So the equation above isn’t meant to suggest a strict template for feedback but a mnemonic to reflect and improve the practice. Even after years of active work on my critiques, I still from time to time go back to this formula and reflect on whether what I just wrote is effective.

The tone

Well-grounded content is the foundation of feedback, but that’s not really enough. The soft skills of the person who’s providing the critique can multiply the likelihood that the feedback will be well received and understood. Tone alone can make the difference between content that’s rejected or welcomed, and it’s been demonstrated that only positive feedback creates sustained change in people.

Since our goal is to be understood and to have a positive working environment, tone is essential to work on. Over the years, I’ve tried to summarize the required soft skills in a formula that mirrors the one for content: the receptivity equation.

Respectful feedback comes across as grounded, solid, and constructive. It’s the kind of feedback that, whether it’s positive or negative, is perceived as useful and fair.

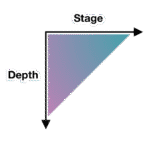

Timing refers to when the feedback happens. To-the-point feedback doesn’t have much hope of being well received if it’s given at the wrong time. Questioning the entire high-level information architecture of a new feature when it’s about to ship might still be relevant if that questioning highlights a major blocker that nobody saw, but it’s way more likely that those concerns will have to wait for a later rework. So in general, attune your feedback to the stage of the project. Early iteration? Late iteration? Polishing work in progress? These all have different needs. The right timing will make it more likely that your feedback will be well received.

Attitude is the equivalent of intent, and in the context of person-to-person feedback, it can be referred to as radical candor. That means checking before we write to see whether what we have in mind will truly help the person and make the project better overall. This might be a hard reflection at times because maybe we don’t want to admit that we don’t really appreciate that person. Hopefully that’s not the case, but that can happen, and that’s okay. Acknowledging and owning that can help you make up for that: how would I write if I really cared about them? How can I avoid being passive aggressive? How can I be more constructive?

Form is relevant especially in a diverse and cross-cultural work environments because having great content, perfect timing, and the right attitude might not come across if the way that we write creates misunderstandings. There might be many reasons for this: sometimes certain words might trigger specific reactions; sometimes nonnative speakers might not understand all the nuances of some sentences; sometimes our brains might just be different and we might perceive the world differently—neurodiversity must be taken into consideration. Whatever the reason, it’s important to review not just what we write but how.

A few years back, I was asking for some feedback on how I give feedback. I received some good advice but also a comment that surprised me. They pointed out that when I wrote “Oh, […],” I made them feel stupid. That wasn’t my intent! I felt really bad, and I just realized that I provided feedback to them for months, and every time I might have made them feel stupid. I was horrified… but also thankful. I made a quick fix: I added “oh” in my list of replaced words (your choice between: macOS’s text replacement, aText, TextExpander, or others) so that when I typed “oh,” it was instantly deleted.